April 22nd 2024

6 Misconceptions About the Vikings

From those famous horned helmets to the vaunted fiery funerals, we’re busting your favorite Viking misconceptions.

- Jake Rossen

Vikings are the focus of countless movies, TV shows, video games, sports teams, and comic books today—but that doesn’t mean we always get them right. From the myths surrounding their horned helmets to their not-so-fiery burial customs, here are some common misconceptions about Vikings, adapted from an episode of Misconceptions on YouTube. https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/MoA36H9KtUw?si=UDEmM-2VQviPvvhe

1. Misconception: Vikings Wore Horned Helmets.

In 1876, German theatergoers were abuzz about a hot new ticket in town. Titled Der Ring des Nibelungen, or The Ring of the Nibelung, Richard Wagner’s musical drama played out over an astounding 15 hours and portrayed Norse and German legends all vying for a magical ring that could grant them untold power. To make his characters look especially formidable, costume designer Carl Emil Doepler made sure they were wearing horned helmets.

Though the image of Vikings plundering and pillaging while wearing horned helmets has permeated popular fiction ever since, the historical record doesn’t quite line up with it. Viking helmets were typically made of iron or leather, and it’s possible some Vikings went without one altogether, since helmets were an expensive item at the time. In fact, archaeologists have uncovered only one authentic Viking helmet, and it was made of iron and sans horns, which some historians and battle experts believe would have had absolutely no combat benefit whatsoever.

So where did Doepler get the idea for horned helmets from? There were earlier illustrations of Vikings in helmets that were occasionally horned (but more often winged). There were also Norse and Germanic priests who wore horned helmets for ceremonial purposes. This was centuries before Vikings turned up, though. Some historians argue that there is some evidence of ritualistic horned helmets in the Viking Age, but if they existed, they would have been decorative horns that priests wore—not something intended for combat.

Composer Richard Wagner apparently wasn’t pleased with the wardrobe choices; he didn’t want his opera to be mired in cheap tropes or grandiose costumes. Wagner’s wife, Cosima, was also irritated, saying that Doepler’s wardrobe smacked of “provincial tastelessness.”

The look wound up taking hold when Der Ring des Nibelungen went on tour through Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Other artists were then inspired by the direction of the musical and began using horned Viking helmets in their own depictions, including in children’s books. Pretty soon, it was standard Viking dress code.

2. Misconception: All Vikings Had Scary Nicknames.

Leif Erikson. Not as scary of a nickname. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

When tales of Viking action spread throughout Europe, they were sometimes accompanied by ferocious-sounding nicknames like Ásgeirr the Terror of the Norwegians and Hlif the Castrator of Horses. This may have been a handy way to refer to Vikings with reputations for being hardcore at a time when actual surnames were in short supply. If you wanted to separate yourself from others with the same name, you needed a nickname. But plenty of them also had less intimidating labels.

Take, for instance, Ǫlver the Friend of Children. Sweet, right? Actually, Ǫlver got his name because he refused to murder children. Then there was Hálfdan the Generous and the Stingy with Food, who was said to pay his men very generously, but apparently didn’t feed them, leading to this contradictory nickname. Ragnarr Hairy Breeches was said to have donned furry pants when he fought a dragon.

Other unfortunate-but-real Viking names include Ulf the Squint-Eyed, Eirik Ale-Lover, Eystein Foul-Fart, Skagi the Ruler of Shit, and Kolbeinn Butter Penis. While the historical record is vague on how these names came to be, the truth is never going to be as good as whatever it is you’re thinking right now.

3. Misconception: Vikings Had Viking Funerals.

When someone like Kolbeinn Butter Penis died, it would only be fitting that they were laid to rest with dignity. And if you know anything about Vikings from pop culture, you know that meant setting them on fire and pushing them out to sea.

But as cool as that visual may be, it’s not exactly accurate. Vikings had funerals similar to pretty much everyone else. When one of them died, they were often buried in the ground. Archaeologists in Norway uncovered one such burial site in 2019, where at least 20 burial mounds were discovered.

The lead archaeologist on the site, Raymond Sauvage of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, told Atlas Obscura that:

“We have no evidence for waterborne Viking funeral pyres in Scandinavia. I honestly do not know where this conception derives from, and it should be regarded as a modern myth. Normal burial practice was that people were buried on land, in burial mounds.”

The flaming ship myth may have come from a combination of two real Viking death practices. Vikings did sometimes entomb their dead in their ships, although the vessels remained on land where they were buried. And they did sometimes have funeral pyres. At some point in the historical record, someone may have combined these two scenarios and imagined that Vikings set ships ablaze before sending them out to sea with their dead still on board.

4. Misconception: Vikings Were Experienced and Trained Combat Soldiers.

Spears and arrows were most cost-effective than swords. (Spencer Arnold Collection/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

While it’s true Vikings were violent, they weren’t necessarily the most experienced or talented warriors of their day. In fact, they were mostly normal people who decided plundering would be a great side hustle in the gig economy of Europe.

Historians believe Vikings were made up mostly of farmers, fishermen, and even peasants, rather than burly Conan the Barbarian types. Considering that the coastal villages they attacked probably didn’t put up much resistance, one could be a Viking and not even have to fight all that much. This leads to another common misconception—that Vikings were always swinging swords around. Like helmets, swords were expensive. A day of fighting was more likely to include spears, axes, long knives, or a bow and arrow.

You can blame this fierce warrior rep on the one squad of Vikings that actually fit the bill. Known as berserkers, these particular Vikings worshipped Odin, the god of war and death, and took Odin’s interests to heart. Some berserkers were said to have fought so fiercely that it was as though they had entered a kind of trance. If they were waiting around too long for a fight to start, it was said they might start killing each other.

5. Misconception: Vikings Were Dirty, Smelly, and Gross.

Most depictions of Vikings would have you believe that they were constantly caked in mud, blood, and other miscellaneous funk. Don’t fall for it. Archaeologists have unearthed a significant amount of personal grooming products over the years that belonged to Vikings, including tweezers, combs, toothpicks, and ear cleaners.

Vikings were also known to have bathed at least once a week, which was a staggeringly hygienic schedule for 11th-century Europe. In fact, Vikings put so much attention on bathing that Saturday was devoted to it. They called it Laugardagur, or bathing day. They even had soap made from animal fat.

Hygiene was only one aspect of their routine. Vikings put time and effort into styling their hair and sometimes even dyed it using lye. Their beards were neatly trimmed, and they were also known to wear eyeliner. All of this preening was said to make Vikings a rather attractive prospect to women in villages they raided, as other men of the era were somewhat reluctant to bathe.

6. Misconception: There Were No Viking Women.

An illustration of Lathgertha, legendary Danish Viking shieldmaiden. (Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Considering the times, Vikings actually had a fairly progressive approach to gender roles. Women could own property, challenge any kind of marriage arrangement, and even request a divorce if things weren’t working out at home. To do so, at least as one story tells it, they’d have to ask witnesses to come over, stand near her bed, and watch as she declared a separation.

In addition to having a relatively high degree of independence, Viking women were also known to pick up a weapon and bash some heads on occasion. The historical record of a battle in 971 CE says that women had fought and died alongside the men. A woman who donned armor was known as a “shieldmaiden.” According to legend, over 300 shieldmaidens fought in the Battle of Brávellir in the 8th century and successfully kept their enemies at bay.

According to History, one of the most notable shieldmaidens was a warrior named Lathgertha who so impressed a famous Viking named Ragnar Lothbrok—he of the Hairy Breeches—that he became smitten and asked for her hand in marriage.

Janauary 15th 2024

How Measuring Time Shaped History

From Neolithic constructions to atomic clocks, how humans measure time reveals what we value most.

- Clara Moskowitz

Humans have tracked time in one way or another in every civilization we have records of, writes physicist Chad Orzel. In his book A Brief History of Timekeeping (BenBella Books, 2022), Orzel chronicles Neolithic efforts to predict solstices and other astronomical events, the latest atomic clocks that keep time to ever more precise decimals and everything that came in between. He describes the evolution of clocks, from water clocks that timed intervals by how long it took water to flow out of a container to hourglasses filled with sand to the first mechanical and pendulum clocks to our modern era. Each episode is filled with interesting physics and engineering, as well as a glimpse at how different ways of keeping time affected how people lived their lives at various points and places in history.

Scientific American talked to Orzel about the coolest clocks in history, the most complicated calendar systems and why we still need to improve the best clocks of today.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

How did the advent of clocks change history?

There’s an interesting democratization of time as you go along. The very most ancient monuments are things such as Newgrange in Ireland. It’s this massive artificial hill with a passage through the center. Once a year sunlight reaches that central chamber, and that tells you it’s the winter solstice. I’ve been there, and you can put 10 to 12 people in there, maybe. This is an elite thing where only a few people have access to this information. As you start to get things such as water clocks, that’s something that individual people can use to time things. They’re not superaccurate, but that makes it more accessible. Mechanical clocks make it even better, and then you get public clocks—clocks on church towers with bells that ring out the hours. Everybody starts to have access to time. Mechanical watches start to become reasonably accurate and reasonably cheap by the 1890s. They cost about one day’s wages. Suddenly everybody has access to accurate timekeeping all the time, and that’s a really interesting change.

Is it hard to track the advent of different kinds of clocks?

When people write about clocks in history, they use the same word for a bunch of different things. There’s a famous example: there was a fire in a particular monastery, and the record says some of the brothers ran to the well, and some ran to the clock. That tells you that it was a water clock because they’re going there to fill up buckets to put the fire out. There’s another reference that says a clock was installed above the rood screen of a church. If it’s 50 feet up in the air, that was probably not a water clock but a mechanical clock because nobody would make a device where you have to go up there and fill it with water.

What is your favorite clock from history?

I really like this Chinese tower clock. It was built in about A.D. 1100 by a court official, Su Song. It’s a water clock, based on a constant flow of water, but it’s a mechanical device. It’s this giant wheel that has buckets at the end of arms, and the bucket is positioned under this constant-flow water source. When it fills past a certain point, the bucket tips, and that releases a mechanism that lets the wheel rotate. The wheel turns and brings a new bucket that starts filling. The timing regulation is really provided by the water, which also provides the drive force. The weight of the water is what’s turning the wheel. It’s this weird hybrid between an old-school water clock and the mechanical clocks that would be developed in Europe a century or two later. It’s an amazingly intricate system, a monumental thing that worked incredibly well. But it didn’t last long—it ran for about 20 years. It was located in a capital city of a particular dynasty, which fell, and the successors couldn’t make it work.

It’s a neat episode in history. The origin of this is that Su Song was sent to offer greetings on the winter solstice to a neighboring kingdom. But the calendar was off by a day. He got there and gave his greeting on the wrong day, which would have been a huge embarrassment. When he got back, the calendar makers were punished, and he said, “I’m fixing this.”

How does a society’s way of keeping time reveal what it values?

Every civilization that we have decent records of has its own way of keeping time. It’s very interesting because there are all these different approaches. None of the natural cycles you see are commensurate with one another. A year is not an integer number of days, and it’s not an integer number of cycles of the moon. So you have to decide what you’re prioritizing over what else. You have systems such as the Islamic calendar, which is strictly lunar. They end up with a calendar that is 12 lunar months, which is short [compared with about 365 days in a solar year], so the dates of the holidays move relative to the seasons.

The Jewish calendar is doing complicated things because they want to keep both: they want holidays to be associated with seasons, so they have to fall in the right part of the year, but they also want them in the right phase of the moon.

The Gregorian calendar sort of splits the difference: We have months whose lengths are sort of based on the moon, but we fix the months, so the solstice is always going to be June 20, 21 or 22. We give the position of the year relative to the seasons priority above everything else.

Then you have the Maya doing something completely different. Their calendar involves this 260-day interval, and no one is completely sure why 260 days was so important.

How accurate are clocks today?

The official time now is based on cesium: one second is 9,192,631,770 oscillations of the light emitted as cesium moves between two particular states.

I can’t believe you know that off the top of your head!

I’ve taught this a bunch of times [laughs].

Time is defined in terms of cesium atoms, so the best clocks in the world are cesium clocks. Cesium clocks are good to a part in 1016. If it says one second, there are 15 zeros after the decimal point before you get to the first uncertain digit. There are experimental clocks that are two, maybe three, orders of magnitude better than that. They are not officially clocks. They are measuring a frequency and measuring it to a better precision than the best cesium clocks.

Those are good enough that an aluminum ion clock did a test of relativity. [Researchers] held the ion fixed in one, and the other, they shook back and forth, and they could see that the one that was moving ticked a little slower. Then they held one in position and moved one about a foot higher, and they could see that the one at higher altitude ticked faster. They agreed perfectly with relativity.

Is there a limit to how accurate clocks can ever be?

There’s a limit in the sense that there are a lot of things that affect the precision. Einstein’s general theory of relatively tells you that the closer you are to a large mass, the slower your clock will tick. At some point, you’re sensitive to the gravitational attraction of graduate students coming into and out of the lab. At that point, it becomes impractical.

This is already an issue because the atomic time for the world is a consensus of atomic clocks all over the world. Here in the U.S., there are two big standards labs: one is the Naval Observatory in Washington D.C., around sea level, and the other is in Boulder, Colo., about a mile up. Their cesium clocks tick at different rates because they’re at different distances from the center of the earth. They have to take that into account. So we kind of made an unwise choice locating this in Boulder.

After all you know about clocks, I have to ask what kind of watch you wear.

I have two: One is a quartz watch—nothing special. I’ve probably spent more replacing the band on it several times than I spent on the watch. The other I have is a mechanical watch from the 1960s. It’s an Omega, purely mechanical watch. It’s an incredibly intricate watch, a marvel of engineering, but I can go to a dollar store and buy a watch that can keep time just as well because quartz is so accurate.

Clara Moskowitz is a senior editor at Scientific American, where she covers astronomy, space, physics and mathematics. She has been at Scientific American for a decade; previously she worked at Space.com. Moskowitz has reported live from rocket launches, space shuttle liftoffs and landings, suborbital spaceflight training, mountaintop observatories and more. She has a bachelor’s degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University and a graduate degree in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

January 4th 2024

Inside the ‘ghost ships’ of the Baltic Sea

Francesca Street, CNN

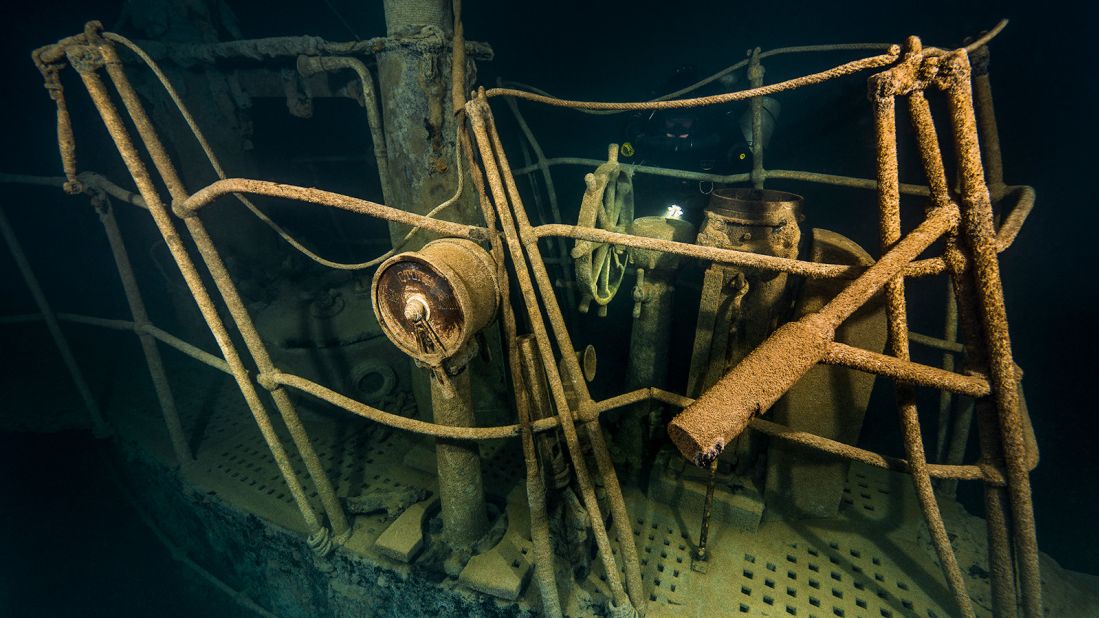

“Ghost ships”: In the icy waters surrounding Scandinavia, divers Jonas Dahm and Carl Douglas explore and photograph wrecks long lost to the ocean, the so-called “ghost ships” of the Baltic Sea. This picture is of an unidentified shipwreck dating possibly from the 17th or 18th centuries.Jonas Dahm

Photographs reveal ‘ghost ships’ of Baltic Sea

1 of 10 CNN —

Plunging into the icy waters surrounding Scandinavia, divers Jonas Dahm and Carl Douglas hunt for vessels long lost to the ocean, what they call the “ghost ships” of the Baltic Sea.

Dahm and Douglas are history lovers and long-time friends who’ve devoted some 25 years of their lives to wreck hunting and research.

While many of the barnacle-clad vessels claimed by the Baltic Sea have lain in wait for centuries, some are in remarkably good condition due to the preservative effects of the water’s chilly temperatures.

On dives, Dahm captures haunting photographs. Intact ship furniture, detailed interior wall carvings and an only-slightly-cracked ship’s clock have all been snapped on the seabed.

Dahm and Douglas also spend hours poring over books, researching the wrecks’ histories.

A selection of Dahm’s eerie photographs, paired with Douglas’ written reflections, feature in the book “Ghost Ships of the Baltic Sea,” published by Swedish publisher Bokförlaget Max Ström.

In the depths of the sea

Dahm took this photograph of a cod swimming past SS Undine, a 19th century German cruiser that became a war vessel during the First World War. The ship sank in the southern Baltic in 1915.Jonas Dahm

The Baltic Sea has been a center for seafaring activity for centuries – from maritime trade to maritime conflict. Inevitably, that means a long history of ships claimed by the waves.

In the book, Douglas writes there are “tens of thousands of intact, undisturbed shipwrecks from every era” submerged in Baltic’s watery depths.

“There still are many that haven’t been found yet,” Dahm tells CNN Travel.

The Baltic Sea’s potential wealth of well-preserved wrecks makes it the home of “the best diving in the world,” says Douglas.

Dahm and Douglas first met in the late 1990s through mutual diving friends in Stockholm, Sweden. Dahm’s been diving since he was a teenager, honing his underwater photography skills during his compulsory military service.

In contrast, Douglas admits he avoided the ocean for a long time.

“I was scared of water – but things that scare often also fascinate,” he tells CNN Travel. After a bit of persuasion from friends, he gave diving a shot.

“After that I was hooked,” he says, while admitting he still gets seasick on boats.

Photographing underwater

Dahm took this photograph of the interior of what was once a passenger cabin on board the Aachen, a 19th century steam ship that sank in the First World War when it became a German navy vessel.Jonas Dahm

Each of Dahm’s images are bathed in a viridescent ocean hue, but key details are also illuminated, as Dahm moves between capturing the heft of the lost ships and zooming in on haunting details.

In the book, Douglas writes about how the divers use “darkness to our advantage.”

“Balancing the natural light from the surface with flashlights and covering as much as possible of the wreck site is the goal,” he says.

Photographer Dahm, who uses Nikon D850 and Fujifilm GFX 100s medium format cameras, works with other divers to maximize time spent under the sea.

“To take the big wide-angle pictures we sometimes are two to three divers working together, while I usually can handle close-ups images by myself,” he explains.

This is a close-up shot of a ship’s chronometer — a type of clock — on one of the wrecks.Jonas Dahm

As well as light, there are are other challenges associated with photographing wrecks – the cold, of course, and the sometimes-opaque visibility.

And there’s the depths, which mean Dahm and Douglas and their team can’t ever linger. The ships featured in the book are submerged as deep as 110 meters (360 feet) under sea.

“At that depth you don’t have very much time to take the photos the way you want,” says Dahm.

The hunt for the world’s most elusive shipwrecks

Unknowable stories

Remnants of the steam ship Rumina.Jonas Dahm

Douglas and Dahm plan trips to particular sites to see particular ships. They get tips from local fishermen, and other times follow in the footsteps of other divers.

But sometimes “a wreck will appear almost randomly on our echo sounder,” as Douglas puts it in the book. Dahm and Douglas love spending time researching the history of their discoveries – particularly when they stumble across anonymous ships, story unknown.

For Dahm, it’s one of these more mysterious wrecks that stands out to him. He calls the ship, the “porcelain wreck,” because it’s still home to treasures includes violins, clay pipes and pocket watches – and yes, several pieces made of porcelain.

“We don’t know its name, why it sank or where it was headed. All we know is that the ship had a valuable cargo and that it did not reach its destination,” says Dahm.

Dahm and Douglas are careful not to damage the wrecks during their exploration. They’re passionate about preserving the sea and marine life. They also approach their photography and their book with respect and care.

“In many cases they represent disasters where people lost their lives under terrible circumstances,” writes Douglas in the book. “We visit these sites with enormous respect, and we do it to honor the victims and tell the story of what happened.”

The book is led by Dahm’s photographs, but Douglas’ accompanying text brings many of the stories to life. He says he wanted his writing to offer insight – there’s input from experts like Dr. Fred Hocker, director of research at Stockholm’s Vasa maritime museum – but the writing also leaves room for questioning and reflecting.

“The writing follows the images,” says Douglas. “We want the reader to really feel the wrecks. Sometimes too much information can ruin that.”

And while the divers love to discover answers to their questions in their research, they also accept not every story is knowable, and find something strangely satisfying in that unknown.

“Sometimes we have to resign ourselves that we will never know the full history – but these mystery wrecks are also very attractive,” says Douglas.

“I will probably never know the answers to all these questions, but it’s okay, most shipwrecks will never reveal their secrets anyway,” says Dahm.

December 12th 2023

A Pint for the Alewives

Until the Plague decimated Europe and reconfigured society, brewing beer and selling it was chiefly the domain of the fairer sex.

Getty Share

By: Akanksha Singh

December 5, 2023

5 minutes

The icon indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR.

As the old sexist saw goes, “Beer is a man’s drink.” Yet, until the fourteenth century, women dominated the field of beer brewing. And the alewife, as she was known, was responsible for a high proportion of ale sales in Europe.

“Ale was virtually the sole liquid consumed by medieval peasants,” writes Judith M. Bennett in a chapter in the edited volume, Women and Work in Preindustrial Europe. “Water was considered to be unhealthy, [so] each household required a large and steady supply of this perishable item.”

Sometimes referred to as a “brewster” (female brewer), the alewife made the drink as part of a typical peasant diet, which also included bread, soups, meat, legumes, and seasonal produce. While most villages depended on local bakers to prepare bread “the skills and equipment required for brewing,” explains Bennett “were readily available in many households.” This included “large pots, vats, ladles, and straining cloths,” implements found even in the poorest households. In other words: anyone who had the time could potentially make and sell ale.

Ale production was time-consuming, and the drink soured within days. The grain needed to make it, usually barley, “had to be soaked for several days, then drained of excess water and carefully germinated to create malt,” writes Bennett. The malt was dried and ground, and then added to hot water for fermentation, following which the wort—the liquid—was drained off and “herbs or yeast could be added as a final touch.”

Most households alternated between making their own ale and buying from and selling to neighbors. Women—wives, mothers, the unmarried, and the widowed—largely oversaw these transactions, writes Christopher Dyer.

“Ale selling was an extension of a common domestic activity: many women brewed for their own household’s consumption, so producing extra for sale was relatively easy,” Dyer explains.

Ale-making was a revolutionary trade for women. “We have heard much in the recent past about the weak work-identity of women, … [how] women were/are dabblers; they fail to attain high skill levels [and] they abandon work when it conflicts with marital or familial obligations,” writes Bennett. But for women of the Middle Ages, making ale was “both practical and rational.” It allowed married women to contribute to household incomes and offered both single women and widows a means to support themselves. This was true, for example, in the English villages of Redgrave and Rickinghall, about 100 miles northeast of London, where records suggested that ale sellers were both poor and single or widowed.

Further west, records from the manorial court of Brigstock show the domestic industry of ale-making to be entirely female dominated.

“The high proportion of women known to have sold ale suggests that all adult women were skilled at brewing ale, even if only some brewed ale for profit,” writes Bennett.

The records that allow us such a close look at ale-making exist in part due to the Assize of Bread and Ale, English regulations from the thirteenth century that created standards of measurement, quality, and pricing for these goods. Since a large number of people sold ale “unpredictably and intermittently,” writes Bennett, “triweekly presentments by ale-tasters” to regulate quality were necessary. “Dominating” the ale trade in the village of Brigstock, according to Bennett, however, was an “elite group” of thirty-eight brewers—alewives—who were “frequently [supplementing] their household economies.”

What’s more, these alewives, particularly in Brigstock, “faced almost no significant male competition,” notes Bennett. “Only a few dozen ale fines were assessed against Brigstock males, and all such men were married to women already active in the ale market.” In the Midlands manor of Houghton-cum-Wyton, on the other hand, some eleven percent of fines were levied against men, while in the manor of Iver in Buckinghamshire, a whopping 71 percent of fines were charged to male brewers.

Broadly, in England around 1300, “a high proportion of women,” writes Dyer, around “a dozen or two in most villages and 100 in larger towns” brewed ale for sale each year. It’s unclear how much the women of Brigstock women earned, on average, through ale-making, but Bennett notes that “the high proportion of women known to have sold ale suggests that all adult women were skilled at brewing ale, even if only some brewed ale for profit.” These alewives weren’t affluent, writes Bennett; they largely came from households “headed by men [of]… modest influence.” In fact, in Brigstock, 74 percent of women were identified as ale “wives” throughout their brewing careers (meaning they were married and unwidowed). In other words, working in the ale trade here wasn’t linked to social status; wives from all backgrounds contributed significantly to household income.

Alewives remained a key part of the production line until roughly 1350, when the Plague decimated communities throughout Europe. After that, male brewers grew in number to meet demand. That doesn’t mean women altogether abandoned the business; those who were linked to a man—as wives or as widows—endured until constraints curtailed their roles, notes historian Patricia T. Rooke. By the 1370s, beer brewing in England was predominantly male.

“That of ‘huswyffe’ (housewife) became valorized at the expense of applewife, alewife, fishwife, or for that matter, glassblower, miller, auctioneer, bricklayer, nun, and prioress,” Rooke writes.

Diverging historical timelines have dispelled the myth that alewives, with their bubbling cauldrons, were hunted alongside witches at the time. (There was a time when alewives were persecuted for being financially independent women, after the Babylonian Hammurabi Code from 1755 BC decreed the death penalty for alewives who insisted on payment in silver rather than in grain.) Still, the alewife lives on in literature, at least. There is Siduri, who dissuades the title character in the Epic of Gilgamesh from continuing his quest to find eternal life, urging him to find happiness in his current world. And in the induction of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, the character Christopher Sly mentions “Marian Hacket, the fat alewife of Wincot,” as he drunkenly calls for more drink.

Today, women brewers continue to carve a space for themselves in the field, hearkening to the unsung role they played through the Victorian era. If beer is indeed a “man’s drink,” it’s really only thanks to women.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.

Have a correction or comment about this article?

Please contact us.

November 8th 2023

- Arts + Culture

- Business + Economy

- Cities

- Education

- Environment

- Health

- Politics + Society

- Science + Tech

- Podcasts

- Insights

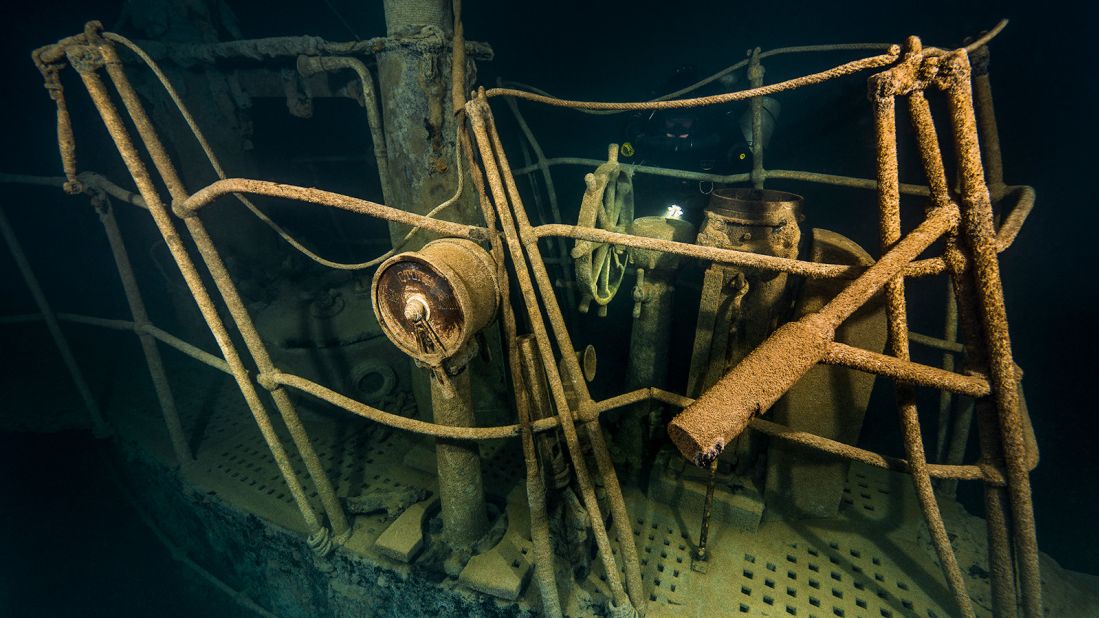

The Great Fire of London by Josepha Jane Battlehooke (1675). Museum of London

Great Fire of London: how we uncovered the man who first found the flames

Published: October 31, 2023 4.47pm GMT

Author

- Kate Loveman Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture, University of Leicester

Disclosure statement

Kate Loveman received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council for this research.

Partners

University of Leicester provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

We believe in the free flow of information

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

If you had been in London on September 2 1666, the chances are you’d remember exactly where you were and who you were with. This was the day the Great Fire began, sweeping across the city for almost five days.

The Museum of London is due to open a new site in 2026. And in preparation for this, curators of the Great Fire gallery decided to examine the stories of everyday Londoners.

As I’d been working with the museum on a project about teaching the Great Fire in schools, I was asked by Meriel Jeater, curator of the Great Fire displays, if I could help research the lives of these Londoners. Top of our list for investigation were the residents of Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane, where the fire began.

There has been lots of excellent work on the Great Fire but, because of ambiguities in the surviving sources, historians have different conclusions about who was in the bakery. Farriner, his wife, children and anonymous servants were among the people mentioned in modern accounts. But it was quickly clear I needed to go back to the manuscript evidence to find answers.

We believe in experts. We believe knowledge must inform decisions

Two types of official investigation into the fire’s causes were carried out in 1666: a parliamentary enquiry and the trial of Robert Hubert, a Frenchman who had falsely confessed to starting the blaze. While you might think Londoners would have a keen interest in who was there at the start of the fire, the surviving accounts of exactly who was present are fragmentary.

Full reports from the enquiries were not published. Meanwhile, most writers at the time were, understandably, much more concerned with the fire’s destructive power than describing its beginnings.

As a result, the clearest account of events in the bakery is in a letter from an MP, Sir Edward Harley, reporting what he had heard. It’s now in the British Library, and was written in October 1666, when the two investigations into the fire were underway:

The Baker of Pudding Lane in whose hous ye Fire began, makes it evident that no Fire was left in his Oven … that his daughter was in ye Bakehous at 12 of ye clock, that between one and two His man was waked with ye choak of ye Smoke, the fire begun remote from ye chimney and Oven, His mayd was burnt in ye Hous not adventuring to Escape as He, his daughter who was much scorched, and his man did out of ye Windore [window] and Gutter.

Narrowing down the suspects

Other details in Harley’s letter suggested he was reliably reporting what he’d learned. The letter provides a list of bakery residents: Thomas Farriner, his unmarried daughter (Hanna), his “man” (meaning trained workman, aka journeyman) and his maid, who died. Other reports don’t mention the “man” or maid, but put Farriner’s son in the bakery.

A document in the London Metropolitan Archives provided more clues. This records the charges against Robert Hubert and – crucially – the names of seven witnesses against him. At the end were: “Thomas Farriner senior, Hanna Farriner, Thomas Dagger, Thomas Farriner Junior”.

Given that Thomas Dagger was sandwiched between the Farriners, Jeater and I suspected that he might be an unrecognised member of the household. Testing this theory, I was able to establish that the indictment’s list of names began with two men who had heard Hubert’s confession and a third who possibly had. The later names, starting with Thomas senior, appeared to be people who could testify to circumstances in the bakery.

This was exciting, because Thomas Dagger looked like a candidate for Farriner’s “man” in Harley’s account, potentially putting a name to the first reported witness of the Great Fire. Searching online archives, I could see there was a baker named Thomas Dagger running a business in Billingsgate after the fire and having many children. But we needed evidence to put Dagger in Pudding Lane.

Sleuthing in the archives

Fortunately, the Bakers’ Company records had not gone up in smoke like so many other guild documents did in September 1666. So I went sleuthing at the Guildhall Library, comparing Bakers’ company information on Farriner’s workforce to names on the indictment.

After much squinting at microfilms, this produced firm evidence for two young men. Thomas Farriner junior had joined the Bakers’ Company in 1669, claiming that right through his father. I was delighted to find Thomas Dagger had indeed worked for Farriner too. He came from Norton in Wiltshire and had been apprenticed to another baker in 1655 before serving out his apprenticeship at Pudding Lane.

That nine-year apprenticeship (unusually long), had ended in 1664, so at the time of the fire he’d stayed on, working unofficially as a journeyman. Of all the names on the indictment, Dagger most clearly matched the description of the man who first discovered the fire.

Continuing the 17th-century investigations into the Great Fire was intriguing, but it’s how the bakery residents’ stories are told that matters. One of the great things about having the life stories of people such as Thomas Dagger is that it will help make the history of London more relevant to young visitors.

For example, if you’re a school child from Wiltshire learning about the Great Fire, Thomas Dagger’s presence in the bakery suddenly makes that national history part of your local history.

As a low-status journeyman, Dagger’s name wasn’t memorable to people in 1666 – he’s barely mentioned in the sources. But the hope is that he and others like him might become memorable to visitors to the new London Museum.

The new research will enable the displays to better represent the Farriner household and provide a fuller understanding of this pivotal moment in London’s history.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

September 23rd 2023

With Speed and Agility, Germany’s Ar 234 Bomber Was a Success That Ultimately Failed

Only one is known to survive today and it is in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

- David Kindy

Read when you’ve got time to spare.

Advertisement

More from Smithsonian Magazine

- How the Death of 6,000 Sheep Spurred the American Debate on Chemical Weapons

- Kurt Vonnegut’s Unpublished World War II Scrapbook Reveals Origins of “Slaughterhouse-Five”

- The Boy Who Became a World War II Veteran at 13 Years Old

Advertisement

Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons

On Christmas Eve, 1944, American forces were dug in around Liege in Belgium and prepared for just about anything. Eight days earlier, four German armies had launched a surprise attack from the Ardennes Forest, using one of the coldest and snowiest winters in European history as cover from Allied air superiority.

The Nazis smashed through stretched-thin defensive positions and were pushing towards the port of Antwerp to cut off Allied supply lines in what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

With savage fighting on many fronts, American troops at Liege were on high alert in case the Germans tried something there—though they didn’t expect what happened next. With the weather clearing, aircraft from both sides were flying once again. High above the Belgian city came the sound of approaching planes. The engine rumble from these aircraft was not typical, though.

Rather than the reverberating growl of piston-driven engines, these aircraft emitted a smooth piercing roar. They were jets, but not Messerschmitt Me 262s, history’s first jet fighter. These were Arado Ar 234 B-2s, the first operational jet bomber to see combat. Nine of them were approaching a factory complex at Liege, each laden with a 1,100-pound bomb.

Luftwaffe Captain Diether Lukesch of Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Wing) 76 led the small squadron on the historic bombing run. Powered by two Jumo 004 B4-1 turbojet engines, the sleek planes zoomed in to drop their payloads and then quickly soared away. They were so fast that Allied fighters could not catch them.

Often overshadowed by more famous jets in World War II, the Ar 234 B-2—known as the Blitz, or Lightning—had caught the Allies by surprise when the nine soared through the skies on December 24, 1944.

History’s first operational jet bomber was designed and built by the Arado company. The plane originally began service as a scout aircraft. One had flown reconnaissance over Normandy snapping photos of supply depots and troop movements just four months earlier. But reconfigured as a bomber and operated by one pilot, who also served as bombardier, the Blitz was fast and agile. It easily eluded most Allied aircraft with its top speed of 456 miles per hour. The Germans also created two other versions of the aircraft—a night fighter and a four-engine heavy bomber—neither made it into full production.

The Allies were keen to capture the Ar 234 so it could be studied. It was not until the end of the war when they finally got their hands on a handful of them.

Only one is known to survive today and it is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

“The Allies were collecting all this German technology after the war,” says curator Alex Spencer. “The Army Air Force spent a good five to six years really studying what these aircraft were capable of doing—both their strengths and weaknesses. Some of the aerodynamic aspects of the Ar 234 and other jets were undoubtedly taken advantage of for some of our early designs, like the F-86 Sabre and other planes.”

The one-person bomber was innovative with its canister fuselage and tricycle landing gear while an autopilot system guided the aircraft on bombing runs and periscope bombing sights allowed for precision attacks. The Ar 234 was at least 100 miles per hour faster than American fighter planes, which could never catch the jet bomber in pursuit. But Allied pilots eventually realized the Blitz was especially vulnerable to attack at slower speeds during takeoff and landing.

Captain Don Bryan of the American Air Force was unsuccessful in his first three attempts to shoot down the Blitz, but he remained determined to score a kill. He finally did in March 1945 when he spotted one making a bombing run on the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen in an attempt to prevent American forces from crossing the Rhine into Germany.

When he saw the jet bomber slow in a tight turn after dropping its payload, Bryan jumped at his chance. Blasting away with the .50-caliber machineguns in his P-51 Mustang, he knocked out one of the jet engines and was then able to get behind the bomber and shoot it down. Bryan’s was the first air-to-air kill of a Blitz.

While the Ar 234 is historic, its effectiveness as a jet bomber is questionable. According to Spencer, it arrived too late in the war and in too few numbers to have any significant impact and was rushed off the drawing board too soon with too many flaws. At best, it was an experimental aircraft that needed more conceptual consideration before it was pressed into service. All told, only a few hundred Ar 234 B-2s were produced with several dozen making it into combat.

“As with most of the so-called German ‘Wonder Weapons,’ they make me wonder,” Spencer says. “Everyone is enamored with them, but they really don’t live up to expectations. Same with the Blitz. It had its good points and bad points. As an attack bomber, it was not that effective.”

During a 10-day period in March 1945, the Luftwaffe flew 400 sorties against the bridge at Remagen in an effort to slow the Allied advance. Ar 234 B-2s from KG 76, as well as other German aircraft, made repeated attacks on the river crossing. All bombs missed their target.

“They made several runs at Remagen and they couldn’t hit the thing,” Spencer says. “It was such a squirrelly aircraft to fly and pilots weren’t used to it. They were learning to fly at speeds they were not used to and their timing was off. It’s new and interesting technology but as far as being a game-changer, I don’t buy the argument.”

The Smithsonian’s Ar 234 was captured by the British in Norway with the surrender of Nazi Germany on May 7, 1945. It had been flown there in the waning days of the war for safekeeping. The English turned over this plane, Werk Nummer 140312, to the Americans, who eventually flew it to a U.S. research facility. In 1949, the U.S. Air Force donated it along with other German aircraft to the Smithsonian. This Blitz had gone through extensive changes so American test pilots could fly it, and the museum undertook a major restoration effort in 1984 to get the Ar 234 back to its wartime condition.

“It was a basket case,” Spencer says. “It took two guys working on it almost five years to restore it. The jet engines and some of the navigational systems had been swapped out during testing, but our staff was able to replace most of that. Some 13,200 man/hours went into returning it to original condition. We’re still missing a few parts, but it’s about as close to 1945 as it can be.”

The restored Ar 234 went on view when work was completed in 1989. News media around the globe reported on the historic aircraft going on display, including a German-language aviation magazine.

In 1990, Willi Kriessmann happened to be leafing through that publication when he spotted the article. The German native, then living in California, read the report with interest and stopped short when he saw the Ar 234’s serial number: 140312. It looked very familiar, so he went and checked his papers from when he flew as a World War II Luftwaffe pilot.

“Out of sheer curiosity, I looked up my logbook, which I saved throughout all the turbulence of the war,” he wrote in his unpublished memoir, which eventually he donated to the Smithsonian. “Eureka! The same serial number!”

Just before Germany’s surrender, Kriessmann had transported the jet to several locations around Germany before flying it to Norway, where both he and the plane were captured by the British. He contacted the Smithsonian and sent along copies of his flight book for authentication. He was invited to the museum to see the Ar 234 again, where he was welcomed by Don Lopez, then deputy director of the National Air and Space Museum.

“I finally faced ‘my bird’ on May 11, 1990,” he wrote. “It was a very emotional reunion.”

The Blitz was moved to the museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center , when the huge expansion site opened in 2003. Kriessmann visited once again at that time. In his memoir, he states how he was saddened that many of his fellow pilots would not be able to join him at the Smithsonian because they had not survived the war. But he was grateful his plane had.

“The (future of the) Ar 234 is now assured, I hope, at least for a while. Maybe eternity,” wrote Kriessmann, who died in 2012.

David Kindy is a former daily correspondent for Smithsonian. He is also a journalist, freelance writer and book reviewer who lives in Plymouth, Massachusetts. He writes about history, culture and other topics for Air & Space, Military History, World War II, Vietnam, Aviation History, Providence Journal and other publications and websites.

June 19th 2023

How the 18th-Century Gay Bar Survived and Thrived in a Deadly Environment

Welcome to the molly house.

- Natasha Frost

More from Atlas Obscura

- How the Black Death Gave Rise to British Pub Culture

- These Masks Brought Shame to Gossips, Drunks, and Narcissists

- How a Threadbare ‘Bag of Secrets’ Led to Guy Fawkes’s Gruesome Execution

Advertisement

Like men’s club houses, molly houses were also places people went simply to socialize, gossip, drink and smoke. Photo from the Wellcome Collection/CC BY 4.0.

In 1709, the London journalist Ned Ward published an account of a group he called “the Mollies Club.” Visible through the homophobic bile (he describes the members as a “Gang of Sodomitical Wretches”) is the clear image of a social club that sounds, most of all, like a really good time. Every evening of the week, Ward wrote, at a pub he would not mention by name, a group of men came together to gossip and tell stories, probably laughing like drains as they did so, and occasionally succumbing to “the Delights of the Bottle.”

In 18th and early-19th-century Britain, a “molly” was a commonly used term for men who today might identify as gay, bisexual or queer. Sometimes, this was a slur; sometimes, a more generally used noun, likely coming from mollis, the Latin for soft or effeminate. A whole molly underworld found its home in London, with molly houses, the clubs and bars where these men congregated, scattered across the city like stars in the night sky. Their locale gives some clue to the kind of raucousness and debauchery that went on within them—one was in the shadow of Newgate prison; another in the private rooms of a tavern called the Red Lion. They might be in a brandy shop, or among the theaters of Drury Lane. But wherever they were, in these places, dozens of men would congregate to meet one another for sex or for love, and even stage performances incorporating drag, “marriage” ceremonies, and other kinds of pageantry.

A 19th-century engraving of London as it was in the later days of the molly house. Photo from the Wellcome Collection/Public Domain.

It’s hard to unpick exactly where molly houses came from, or when they became a phenomenon in their own right. In documents from the prior century, there is an abundance of references to, and accounts of, gay men in London’s theaters or at court. Less overtly referenced were gay brothels, which seem harder to place than their heterosexual equivalents. (The historian Rictor Norton suggests that streets once called Cock’s Lane and Lad Lane may lend a few clues.) Before the 18th century, historians Jeffrey Merrick and Bryant Ragan argue, sodomy was like any other sin, and its proponents like any other sinners, “engaged in a particular vice, like gamblers, drunks, adulterers, and the like.”

But in the late 17th century, a certain moral sea change left men who had sex with men under more scrutiny than ever before. Part of this stemmed from a fear of what historian Alan Bray calls the “disorder of sexual relations that, in principle, at least, could break out anywhere.” Being a gay man became more and more dangerous. In 1533, Henry VIII had passed the Buggery Act, sentencing those found guilty of “unnatural sexual act against the will of God and man” to death. In theory, this meant anal sex or bestiality. In practice, this came to mean any kind of sexual activity between two men. At first, the law was barely applied, with only a handful of documented cases in the 150 years after it was first passed—but as attitudes changed, it began to be more vigorously applied.

Men found guilty of buggery would be sentenced to death by hanging, with members of the public congregating to watch their execution. Photo from the Public Domain.

The moral shift ushered in a belief that sodomy was more serious than all other crimes. Indeed, writes Ian McCormick, “in its sinfulness, it also included all of them: from blasphemy, sedition, and witchcraft, to the demonic.” While Oscar Wilde might call homosexuality “the love that dare not speak its name,” others saw it as a crime too shocking to name, with “language … incapable of sufficiently expressing the horror of it.” Other commenters of the time, trying to wrangle with the idea, seem incapable of getting beyond the impossible question of why women would not be sufficient for these men:

“’Tis strange that in a Country where

Our Ladies are so Kind and Fair,

So Gay, and Lovely, to the Sight,

So full of Beauty and Delight;

That Men should on each other doat,

And quit the charming Petticoat.”

In this climate, molly houses were an all-too-necessary place of refuge. Sometimes, these were houses, with a mixture of permanent lodgers and occasional visitors. Others were hosted in taverns. All had two things in common—they were sufficiently accessible that a stranger in the know could enter without too much hassle; and there was always plenty to drink.

Samuel Stevens was an undercover agent for the Reformation of Manners, a religious organization that vowed to put a stop to everything from sodomy to sex work to breaking the Sabbath. In 1724, he led a police constable to one such house on Beech Lane, where the brutalist Barbican Estate is today. “There I found a company of men fiddling and dancing and singing bawdy songs, kissing and using their hands in a very unseemly manner,” the policeman, Joseph Sellers, is recorded as having said in court. Elsewhere, the men sprawled across one another’s laps, “talked bawdy,” and took part in country dances. Others peeled off to other rooms to have sex in what they believed to be relative safety.

Sex may have been at the root of the matter, but everything around it—the drinking, the flirting, the camaraderie—was every bit as important. In the minds of the general public, molly houses were dens of sin. But, for their regular customers, writes Bray, “they must have seemed like any ghetto, at times claustrophobic and oppressive, at others warm and reassuring. It was a place to take off the mask.” Here, men pushed to the fringes of society could find their community.

It’s probable that a certain amount of sex work took place, though how much money really changed hands is hard to tease out. “Homosexual prostitution was of only marginal significance,” writes Norton. Instead, “men bought their potential partners beer.” More moralizing commentators mistook consensual sexual activity for more mercenary sex work, using “terms such as ‘He-Strumpets’ and ‘He-Whores’ even for quite ordinary gay men who would never think of soliciting payment for their pleasures.”

An 18th-century engraving, A Morning Frolic, or the Transmutation of the Sexes, shows two people in various stages of drag. Photo from the Public Domain.

Because so many accounts of these molly houses came from people like the agent, Stevens, or the journalist, Ward, who wanted the houses closed and their customers sanctioned, they tend towards the salacious. Many focus on sexual activity or on particular aspects of this nascent gay culture that seemed shocking or foreign to these unwanted observers. One account delivered in the court known as the Old Bailey creates a vivid picture of an early drag ball. “Some were completely rigged in gowns, petticoats, headcloths, fine laced shoes, befurbelowed scarves, and masks; some had riding hoods, some were dressed like milkmaids, others like shepherdesses with green hats, waistcoats, and petticoats; and others had their faces patched and painted and wore very extensive hoop petticoats, which had been very lately introduced.” In a slew of costumes and colors, they danced, drank, and made merry.

Drag seems to have been common in molly houses, sometimes veering into kinds of pantomime that don’t quite have a modern equivalent. In Ward’s article about the Mollies Club, he describes how the men, who called one another “sister,” would dress up one of their party in a woman’s night-gown. Once they were in costume, this person then pretended to be giving birth, he wrote, and “to mimic the wry Faces of a groaning Woman.” A wooden baby was brought forth, everyone celebrated and a pageant baptism took place. Others dressed up as nurses and midwives—they would crowd around the baby, “being as intent upon the Business in hand, as if they had been Women, the Occasion real, and their Attendance necessary.” A celebratory meal of cold tongue and chicken was served, and everyone feasted to commemorate their bouncing new arrival, with “the eyes, Nose, and Mouth of its own credulous Daddy.”

Men of all social classes mingled in the molly house. Photo from the Wellcome Collection/CC BY 4.0.

At one of the most famous molly houses, owned by Margaret Clap, couples slipped into another room, two-by-two, to be “married.” In “The Marrying Room,” or “The Chapel,” a marriage attendant stood by, guarding the door to give the happy couple some privacy as they made use of the double bed. (“Often,” Norton writes, “the couple did not bother to close the door behind them.”) At the White Swan, on Vere Street, John Church, an ordained minister, performed marriage ceremonies for those who wanted them—though it’s unknown whether these nuptials were expected to last more than a single evening.

The openness that allowed men seeking sex with men to find molly houses exposed them to the risk of raids, and subsequent convictions. Police constables would occasionally swarm into the festivities, rounding up the men they found there and hauling them off to prison, where they would await trial. In the mid-1720s, there was a rash of these raids, leading many men to the gallows. Embittered informants who were intimately familiar with the molly houses would allow police to pose as their “husbands” in order to infiltrate the club. These constables would be welcomed into the fold—then return later to close it up for good and use what they had seen against the members.

A 1707 broadsheet illustration shows two men embracing. On the left, one cuts his throat when his friend is hanged. On the right, a man is cut down from the gallows. Photo from the Public Domain.

In 1810, one of the most famous raids took place on the White Swan. It had barely been open six months when police stormed the place, arresting about 30 of the people they found inside. A violent mob, of which the women were apparently “most ferocious,” surged around the prisoners’ coaches as they made their way to the watch house. Two were sentenced for buggery, and put to death. A larger number, convicted of “running a disorderly house,” were mostly sentenced to many humiliating hours in the pillory, where members of the public could throw things at them. Three months after the original raid, these men were led through the streets and out onto the pillory. As they went, thousands of people formed a seething crowd, hurling whatever they could at them—dead cats, mud pellets, putrid fish and eggs, dung, potatoes, slurs. The men began to bleed profusely from their wounds. After an hour in the pillory, about 50 women formed a ring around them, pelting them with object after object. One man was beaten until he was unconscious.

These raids forced molly houses, and men who had sex with men, deeper underground. The subculture didn’t die out, but the establishments often did, or became harder to find. And then, in 1861, a sliver of light—the death penalty for sodomy or buggery was repealed and replaced with nebulous legislation around “gross indecency.” (It was for this charge that Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for two years, four decades later.) It would be another 106 years after the repeal that sex between men was decriminalized altogether in the United Kingdom, by which time the molly house was all but forgotten, and its patrons nearly scrubbed from the history books.

May 10th 2023

What Happens When You Kill Your King

After the English Revolution—and an island’s experiment with republicanism—a genuine restoration was never in the cards.

By Adam Gopnik

April 17, 2023

Jonathan Healey’s “The Blazing World” sees both sectarian strife and galvanizing political ideas in the civil wars—and in the fateful conflict between Cromwell and Charles I.Illustration by Wesley Allsbrook

Amid the pageantry (and the horrible family intrigue) of the approaching coronation, much will be said about the endurance of the British monarchy through the centuries, and perhaps less about how the first King Charles ended his reign: by having his head chopped off in public while the people cheered or gasped. The first modern revolution, the English one that began in the sixteen-forties, which replaced a monarchy with a republican commonwealth, is not exactly at the forefront of our minds. Think of the American Revolution and you see pop-gun battles and a diorama of eloquent patriots and outwitted redcoats; think of the French Revolution and you see the guillotine and the tricoteuses, but also the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Think of the English Revolution that preceded both by more than a century and you get a confusion of angry Puritans in round hats and likable Cavaliers in feathered ones. Even a debate about nomenclature haunts it: should the struggles, which really spilled over many decades, be called a revolution at all, or were they, rather, a set of civil wars?

According to the “Whig” interpretation of history—as it is called, in tribute to the Victorian historians who believed in it—ours is a windup world, regularly ticking forward, that was always going to favor the emergence of a constitutional monarchy, becoming ever more limited in power as the people grew in education and capacity. And so the core seventeenth-century conflict was a constitutional one, between monarchical absolutism and parliamentary democracy, with the real advance marked by the Glorious Revolution, and the arrival of limited monarchy, in 1688. For the great Marxist historians of the postwar era, most notably Christopher Hill, the main action had to be parsed in class terms: a feudal class in decline, a bourgeois class in ascent—and, amid the tectonic grindings between the two, the heartening, if evanescent, appearance of genuine social radicals. Then came the more empirically minded revisionists, conservative at least as historians, who minimized ideology and saw the civil wars as arising from the inevitable structural difficulties faced by a ruler with too many kingdoms to subdue and too little money to do it with.

The point of Jonathan Healey’s new book, “The Blazing World” (Knopf), is to acknowledge all the complexities of the episode but still to see it as a real revolution of political thought—to recapture a lost moment when a radically democratic commonwealth seemed possible. Such an account, as Healey recognizes, confronts formidable difficulties. For one thing, any neat sorting of radical revolutionaries and conservative loyalists comes apart on closer examination: many of the leading revolutionaries of Oliver Cromwell’s “New Model” Army were highborn; many of the loyalists were common folk who wanted to be free to have a drink on Sunday, celebrate Christmas, and listen to a fiddler in a pub. (All things eventually restricted by the Puritans in power.)

The Best Books We Read This Week

Something like this is always true. Revolutions are won by coalitions and only then seized by fanatics. There were plenty of blue bloods on the sansculottes side of the French one, at least at the beginning, and the American Revolution joined abolitionists with slaveholders. One of the most modern aspects of the English Revolution was Cromwell’s campaign against the Irish Catholics after his ascent to power; estimates of the body count vary wildly, but it is among the first organized genocides on record, resembling the Young Turks’ war against the Armenians. Irish loyalists, forced to take refuge in churches, were burned alive inside them.

Healey, a history don at Oxford, scants none of these things. A New Model social historian, he writes with pace and fire and an unusually sharp sense of character and humor. At one emotional pole, he introduces us to the visionary yet perpetually choleric radical John Lilburne, about whom it was said, in a formula that would apply to many of his spiritual heirs, that “if there were none living but himself John would be against Lilburne, and Lilburne against John.” At the opposite pole, Healey draws from obscurity the mild-mannered polemicist William Walwyn, who wrote pamphlets with such exquisitely delicate titles as “A Whisper in the Ear of Mr Thomas Edward” and “Some Considerations Tending to the Undeceiving of Those, Whose Judgements Are Misinformed.”

For Hill, the clashes of weird seventeenth-century religious beliefs were mere scrapings of butter on the toast of class conflict. If people argue over religion, it is because religion is an extension of power; the squabbles about pulpits are really squabbles about politics. Against this once pervasive view, Healey declares flatly, “The Civil War wasn’t a class struggle. It was a clash of ideologies, as often as not between members of the same class.” Admiring the insurgents, Healey rejects the notion that they were little elves of economic necessity. Their ideas preceded and shaped the way that they perceived their class interests. Indeed, like the “phlegmatic” and “choleric” humors of medieval medicine, “the bourgeoisie” can seem a uselessly encompassing category, including merchants, bankers, preachers, soldiers, professionals, and scientists. Its members were passionate contestants on both sides of the fight, and on some sides no scholar has yet dreamed of.

Healey insists, in short, that what seventeenth-century people seemed to be arguing about is what they were arguing about. When members of the influential Fifth Monarchist sect announced that Charles’s death was a signal of the Apocalypse, they really meant it: they thought the Lord was coming, not the middle classes. With the eclectic, wide-angle vision of the new social history, Healey shows that ideas and attitudes, rhetoric and revelations, rising from the ground up, can drive social transformation. Ripples on the periphery of our historical vision can be as important as the big waves at the center of it. The mummery of signatures and petitions and pamphlets which laid the ground for conflict is as important as troops and battlefield terrain. In the spirit of E. P. Thompson, Healey allows members of the “lunatic fringe” to speak for themselves; the Levellers, the Ranters, and the Diggers—radicals who cried out in eerily prescient ways for democracy and equality—are in many ways the heroes of the story, though not victorious ones.

But so are people who do not fit neatly into tales of a rising merchant class and revanchist feudalists. Women, shunted to the side in earlier histories of the era, play an important role in this one. We learn of how neatly monarchy recruited misogyny, with the Royalist propaganda issuing, Rush Limbaugh style, derisive lists of the names of imaginary women radicals, more frightening because so feminine: “Agnes Anabaptist, Kate Catabaptist . . . Penelope Punk, Merald Makebate.” The title of Healey’s book is itself taken from a woman writer, Margaret Cavendish, whose astonishing tale “The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World” was a piece of visionary science fiction that summed up the dreams and disasters of the century. Healey even reports on what might be a same-sex couple among the radicals: the preacher Thomas Webbe took one John Organ for his “man-wife.”

What happened in the English Revolution, or civil wars, took an exhaustingly long time to unfold, and its subplots were as numerous as the bits of the Shakespeare history play the wise director cuts. Where the French Revolution proceeds in neat, systematic French parcels—Revolution, Terror, Directorate, Empire, etc.—the English one is a mess, exhausting to untangle and not always edifying once you have done so. There’s a Short Parliament, a Long Parliament, and a Rump Parliament to distinguish, and, just as one begins to make sense of the English squabbles, the dour Scots intervene to further muddy the story.

In essence, though, what happened was that the Stuart monarchy, which, after the death of Elizabeth, had come to power in the person of the first King James, of Bible-version fame, got caught in a kind of permanent political cul-de-sac. When James died, in 1625, he left his kingdom to his none too bright son Charles. Parliament was then, as now, divided into Houses of Lords and Commons, with the first representing the aristocracy and the other the gentry and the common people. The Commons, though more or less elected, by uneven means, served essentially at the King’s pleasure, being summoned and dismissed at his will.

Video From The New YorkerMy Parent, Neal: Transitioning at Sixty-two

Parliament did, however, have the critical role of raising taxes, and, since the Stuarts were both war-hungry and wildly incompetent, they needed cash and credit to fight their battles, mainly against rebellions in Scotland and Ireland, with one disastrous expedition into France. Although the Commons as yet knew no neat party divides, it was, in the nature of the times, dominated by Protestants who often had a starkly Puritan and always an anti-papist cast, and who suspected, probably wrongly, that Charles intended to take the country Catholic. All of this was happening in a time of crazy sectarian religious division, when, as the Venetian Ambassador dryly remarked, there were in London “as many religions as there were persons.” Healey tells us that there were “reports of naked Adamites, of Anabaptists and Brownists, even Muslims and ‘Bacchanalian’ pagans.”

In the midst of all that ferment, mistrust and ill will naturally grew between court and Parliament, and between dissident factions within the houses of Parliament. In January, 1642, the King entered Parliament and tried to arrest a handful of its more obnoxious members; tensions escalated, and Parliament passed the Militia Ordinance, awarding itself the right to raise its own fighting force, which—a significant part of the story—it was able to do with what must have seemed to the Royalists frightening ease, drawing as it could on the foundation of the London civic militia. The King, meanwhile, raised a conscript army of his own, which was ill-supplied and, Healey says, “beset with disorder and mutiny.” By August, the King had officially declared war on Parliament, and by October the first battle began. A series of inconclusive wins and losses ensued over the next couple of years.

The situation shifted when, in February, 1645, Parliament consolidated the New Model Army, eventually under the double command of the aristocratic Thomas Fairfax, about whom, one woman friend admitted, “there are various opinions about his intellect,” and the grim country Protestant Oliver Cromwell, about whose firm intellect opinions varied not. Ideologically committed, like Napoleon’s armies a century later, and far better disciplined than its Royalist counterparts, at least during battle (they tended to save their atrocities for the after-victory party), the New Model Army was a formidable and modern force. Healey, emphasizing throughout how fluid and unpredictable class lines were, makes it clear that the caste lines of manners were more marked. Though Cromwell was suspicious of the egalitarian democrats within his coalition—the so-called Levellers—he still declared, “I had rather have a plain russet-coated captain that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman.”

Throughout the blurred action, sharp profiles of personality do emerge. Ronald Hutton’s marvellous “The Making of Oliver Cromwell” (Yale) sees the Revolution in convincingly personal terms, with the King and Cromwell as opposed in character as they were in political belief. Reading lives of both Charles and Cromwell, one can only recall Alice’s sound verdict on the Walrus and the Carpenter: that they were both very unpleasant characters. Charles was, the worst thing for an autocrat, both impulsive and inefficient, and incapable of seeing reality until it was literally at his throat. Cromwell was cruel, self-righteous, and bloodthirsty.

Yet one is immediately struck by the asymmetry between the two. Cromwell was a man of talents who rose to power, first military and then political, through the exercise of those talents; Charles was a king born to a king. It is still astounding to consider, in reading the history of the civil wars, that so much energy had to be invested in analyzing the character of someone whose character had nothing to do with his position. But though dynastic succession has been largely overruled in modern politics, it still holds in the realm of business. And so we spend time thinking about the differences, say, between George Steinbrenner and his son Hal, and what that means for the fate of the Yankees, with the same nervous equanimity that seventeenth-century people had when thinking about the traits and limitations of an obviously dim-witted Royal Family.

Although Cromwell emerges from every biography as a very unlikable man, he was wholly devoted to his idea of God and oddly magnetic in his ability to become the focus of everyone’s attention. In times of war, we seek out the figure who embodies the virtues of the cause and ascribe to him not only his share of the credit but everybody else’s, too. Fairfax tended to be left out of the London reports. He fought the better battles but made the wrong sounds. That sentence of Cromwell’s about the plain captain is a great one, and summed up the spirit of the time. Indeed, the historical figure Cromwell most resembles is Trotsky, who similarly mixed great force of character with instinctive skill at military arrangements against more highly trained but less motivated royal forces. Cromwell clearly had a genius for leadership, and also, at a time when religious convictions were omnipresent and all-important, for assembling a coalition that was open even to the more extreme figures of the dissident side. Without explicitly endorsing any of their positions, Cromwell happily accepted their support, and his ability to create and sustain a broad alliance of Puritan ideologies was as central to his achievement as his cool head with cavalry.

Hutton and Healey, in the spirit of the historians Robert Darnton and Simon Schama—recognizing propaganda as primary, not merely attendant, to the making of a revolution—bring out the role that the London explosion of print played in Cromwell’s triumph. By 1641, Healey explains, “London had emerged as the epicentre of a radically altered landscape of news . . . forged on backstreet presses, sold on street corners and read aloud in smoky alehouses.” This may be surprising; we associate the rise of the pamphlet and the newspaper with a later era, the Enlightenment. But just as, once speed-of-light communication is possible, it doesn’t hugely matter if its vehicle is telegraphy or e-mail, so, too, once movable type was available, the power of the press to report and propagandize didn’t depend on whether it was produced single sheet by single sheet or in a thousand newspapers at once.

At last, at the Battle of Naseby, in June, 1645, the well-ordered Parliamentary forces won a pivotal victory over the royal forces. Accident and happenstance aided the supporters of Parliament, but Cromwell does seem to have been, like Napoleon, notably shrewd and self-disciplined, keeping his reserves in reserve and throwing them into battle only at the decisive moment. By the following year, Charles I had been captured. As with Louis XVI, a century later, Charles was offered a perfectly good deal by his captors—basically, to accept a form of constitutional monarchy that would still give him a predominant role—but left it on the table. Charles tried to escape and reimpose his reign, enlisting Scottish support, and, during the so-called Second Civil War, the bloodletting continued.

In many previous histories of the time, the battles and Cromwell’s subsequent rise to power were the pivotal moments, with the war pushing a newly created “middling class” toward the forefront. For Healey, as for the historians of the left, the key moment of the story occurs instead in Putney, in the fall of 1647, in a battle of words and wills that could easily have gone a very different way. It was there that the General Council of the New Model Army convened what Healey calls “one of the most remarkable meetings in the whole of English history,” in which “soldiers and civilians argued about the future of the constitution, the nature of sovereignty and the right to vote.” The implicit case for universal male suffrage was well received. “Every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government,” Thomas Rainsborough, one of the radical captains, said. By the end of a day of deliberation, it was agreed that the vote should be extended to all men other than servants and paupers on relief. The Agitators, who were in effect the shop stewards of the New Model Army, stuck into their hatbands ribbons that read “England’s freedom and soldier’s rights.” Very much in the manner of the British soldiers of the Second World War who voted in the first Labour government, they equated soldiery and equality.

The democratic spirit was soon put down. Officers, swords drawn, “plucked the papers from the mutineers’ hats,” Healey recounts, and the radicals gave up. Yet the remaining radicalism of the New Model Army had, in the fall of 1648, fateful consequences. The vengeful—or merely egalitarian—energies that had been building since Putney meant that the Army objected to Parliament’s ongoing peace negotiations with Charles. Instead, he was tried for treason, the first time in human memory that this had happened to a monarch, and, in 1649, he was beheaded. In the next few years, Cromwell turned against Parliament, impatient with its slow pace, and eventually staged what was in effect a coup to make himself dictator. “Lord Protector” was the title Cromwell took, and then, in the way of such things, he made himself something very like a king.

Cromwell won; the radicals had lost. The political thought of their time—however passionate—hadn’t yet coalesced around a coherent set of ideas and ideals that could have helped them translate those radical intuitions into a persuasive politics. Philosophies count, and these hadn’t been, so to speak, left to simmer on the Hobbes long enough: “Leviathan” was four years off, and John Locke was only a teen-ager. The time was still recognizably and inherently pre-modern.