Home | The Drake Exploration Society HomeAbout

usDrake

ResearchLife and

voyagesDiscoveriesDrake-ing Cape

HornArtefacts

Bombers Moon – YouTubehttps://www.youtube.com › watch6:40Provided to YouTube by The Orchard Enterprises Bombers Moon · Mike Harding Bombers‘ Moon … The Bar …20 Nov 2014 · Uploaded by Mike Harding – Topic

August 18th 2022

How Suffragists Raced to Secure Women’s Right to Vote Ahead of the 1920 ElectionThe 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920—just in time to include women voters in the presidential election.Read More The Origins of 7 Popular SportsDid you know that golf was invented before Abraham Lincoln was born, but basketball didn’t exist until decades after his death?Read More When Gandhi’s Salt March Rattled British Colonial RuleIn 1930, Mahatma Gandhi and his followers set off on a 241-mile march to the coastal town of Dandi to lay Indian claim to the nation’s own salt.Read More 8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman MedicineWhile doctors in ancient Rome prescribed macabre elixirs and used dreams for diagnoses, they also made significant medical advances.Read More Don’t miss a new episode of Colosseum this Sunday, August 21 at 9/8c on The HISTORY Channel. Stream Episode 1 in the HISTORY App. How Suffragists Raced to Secure Women’s Right to Vote Ahead of the 1920 ElectionThe 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920—just in time to include women voters in the presidential election.Read More The Origins of 7 Popular SportsDid you know that golf was invented before Abraham Lincoln was born, but basketball didn’t exist until decades after his death?Read More When Gandhi’s Salt March Rattled British Colonial RuleIn 1930, Mahatma Gandhi and his followers set off on a 241-mile march to the coastal town of Dandi to lay Indian claim to the nation’s own salt.Read More 8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman MedicineWhile doctors in ancient Rome prescribed macabre elixirs and used dreams for diagnoses, they also made significant medical advances.Read More Don’t miss a new episode of Colosseum this Sunday, August 21 at 9/8c on The HISTORY Channel. Stream Episode 1 in the HISTORY App. |

August 10th 2022

Six Books to Guide You Through the Real American West

These novels remind readers that the story of the region is as vast as its landscape.By Kali Fajardo-Anstine

In the second half of the 19th century, the figure of the cowboy emerged as the defining feature of American Western literature. Publishers found success with dime Westerns, novels mythologizing the lives of “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Kit Carson, Wyatt Earp, and other dubious frontiersmen. Decades later, when film became a dominant form of mass entertainment, the moving image of this lonesome and troubled white man riding on horseback would come to personify the ethos of an entire region, a metaphor for a young and white America, heroically subduing the supposedly barren landscape.

My debut novel, Woman of Light, is also a Western saga. It is propelled by five generations of Chicana and Indigenous women and is based on my family’s oral tradition in what is now known as Colorado. In response to the saturating mythos of the white cowboy, my novel includes markers of the Western genre, such as sharpshooters and Wild West shows, but it breaks away from these rigid confines to offer a more naturalistic view of the American West from the late 19th century through the Great Depression.

I’ve always admired writers who have worked to dispel myths about the West. I am especially drawn to the novels that have illuminated a wide range of people who inhabit the region. Some of these books are now considered classics, but there are newer titles, too, that tell the truths of our communities. These six novels provide a sharper rendering of Western stories and a broader view of the region that has captured the world’s imagination for centuries.

The Rain God, by Arturo Islas

An exquisite multigenerational novel by Islas, a pioneering Chicano writer, The Rain God follows the Angel clan along the Texas-Mexico border, where descendants of the stern and pious Mama Chona hold one another in a complex familial embrace. Born in El Paso in 1938, Islas became the first Chicano to publish a novel with a major New York press in 1990, but died one year later of AIDS-related complications at age 52. Widely considered a masterpiece, The Rain God is taught in many literature and Chicano-studies classes across the country for its groundbreaking portrait of the central family. The novel’s matriarch was a young woman in Mexico when her firstborn, a brilliant university student, was gunned down in San Miguel de Allende during the Mexican Revolution. The Angel family is thrust north to the desert. Readers receive an intimate glimpse of this web of children and grandchildren, friends, and neighbors. In vivid realist scenes, this masterwork of American literature touches on themes of border consciousness, queerness, and the inescapable finality of death.

Geek Love, by Katherine Dunn

Born in Kansas in 1945, Dunn was the daughter of migrant farmworkers and sharecroppers. Her family of five siblings roved throughout the American West before settling in Oregon, a childhood Dunn considered a “standard Western American life.” Her third novel, the grotesque carnival saga Geek Love, follows a similarly roaming family of five children—the Binewskis of the Carnival Fabulon. Aloysius and Crystal Lil Binewski run a traveling circus; when it falters, they decide to genetically modify their own children into sideshow “freaks” through use of radiation and toxic drugs. The result is one of the most unforgettable and unique families in American literature. Told in two timelines, Geek Love is narrated by the now adult Oly, a Portland radio host and a dwarf with albinism and a hunchback who is determined to keep her family history alive for her estranged daughter. The novel, bursting with creative genius, displays Dunn’s prodigious understanding of family dynamics, especially among siblings in this marginalized troupe of performers.

Read: Before Geek Love, Katherine Dunn gave us Attic

My Ántonia, by Willa Cather

Frequently called a classic, Cather’s fourth novel, My Ántonia, is rapturous with prairie imagery and depictions of the 1918 book’s shining star, the resilient and uncommonly brave Ántonia Shimerda. Told from the perspective of the orphaned Jim Burden, who is sent from Virginia to live with his grandparents in Nebraska, this moving story of human connection across time is a page-turner propelled by a deeply emotionally intelligent voice. Jim first encounters Ántonia and her Bohemian immigrant family while traveling by train to the Great Plains. Once settled in Nebraska, Jim forms a close friendship with Ántonia and witnesses her strength after her father dies by suicide. Scholars debate Cather’s queerness, but My Ántonia is easily read as a queer-coded text, one in which Jim and Ántonia are not connected through the usual trappings of heteronormative romance. Instead, as they grow up, they embrace the human need to understand the weight of our early beginnings and trace how our foundational relationships shape our futures.

Under the Feet of Jesus, Helena María Viramontes

Viramontes’s first novel, published in 1995 and dedicated in part to Cesar Chavez, is a saturated, sensory experience through the grape fields of California’s Central Valley. The book is slim, but each achingly realistic scene teems with life as its main character and her family of farmworkers navigate corruption and dangerous labor conditions. In lush and commanding prose, we come to know Estrella, who was abandoned by her father as a young girl. When Estrella is a teenager, her mother, Petra, discovers that she is unexpectedly pregnant by her new companion, Perfecto, who misses his home and wrestles with the decision to stay or leave for Mexico. With gorgeous, sweeping sentences, pared-down dialogue, and keen attention to workers’ lives, this haunting novel has been compared to the work of John Steinbeck and William Faulkner. Under the Feet of Jesus is a true wonder that leaves the reader with a greater understanding of the American West and the people who are vital to our food supply.

Where the Dead Sit Talking, by Brandon Hobson

A compulsively honest narrator is mesmerizing, and the voice behind Hobson’s 2018 novel, Where the Dead Sit Talking, is absolutely transfixing. In this darkly strange yet comforting story, a Cherokee man named Sequoyah reflects on his time in the foster-care system as a teenager. Like his ancestors before him, Sequoyah and his mother are pushed out of Cherokee County. His mother, meandering through a maze of poverty and addiction, soon is imprisoned for driving while under the influence and for possession of drug paraphernalia. Sequoyah is eventually placed in rural Oklahoma with the Troutt family, who have two other foster children, George and Rosemary. On the opening page, we learn that Rosemary, a 17-year-old Indigenous girl, will die in front of Sequoyah. This impulse toward hard-edged truths endears Sequoyah to the reader in a rare and vital way, spotlighting Indigenous experiences that have so violently been overlooked by mainstream Western literature. “People live and die. Death is quick,” says Sequoyah by the novel’s end, teaching us and himself about the realities of our frequently painful human existence, so marked by loss.

Four Treasures of the Sky, by Jenny Tinghui Zhang

Four Treasures of the Sky, an adventurous and ambitious debut novel, follows Daiyu, a 13-year-old girl kidnapped from a fish market in China in 1882. Daiyu’s grandmother disguises her as a boy in order to protect her, and she is then sent to work in a calligraphy school, but despite her concealment, she is eventually trafficked to a brutal San Francisco brothel. In this new and strange land, Daiyu survives by constantly adapting to her surroundings. The novel was inspired by a historical marker describing a little-known vigilante murder in 1885 Idaho, where five Chinese men were hanged. Zhang’s powerful debut reminds us of some of the more hideous parts of the American past while illuminating white supremacy’s lingering, contemporary poison. Meticulously researched and historically illuminating, Four Treasures of the Sky offers a careful examination of character and the devastating impacts of anti-Chinese sentiment across the West.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

January 23rd 2022

‘Women and children first’ onto the Titanic lifeboats was a myth, historian claims

Hannah Furness

It is one of the most enduring sentiments of a seemingly lost age of chivalry: “Women and children first.”

Read More ‘Women and children first’ onto the Titanic lifeboats was a myth, historian claims (msn.com)

They were the world’s richest family, until their dynasty was destroyed

Danielle McAdam

Once the richest family in the world, the House of Romanov was Russia’s ruling dynastic family for over 300 years from 1613 until its deposition in 1917. Each new generation of rulers led to a fresh set of torrid tales, including brutal murders, family betrayals, and assassination plots. The heinous history of the super-rich House of Romanov and their vile regime gave birth to communism.

January 11th 2022

Medieval warhorses no bigger than modern-day ponies, study finds

Steven Morris

In films and literature they are usually depicted as hulking, foot-stomping, snorting beasts but a new study has claimed that the medieval warhorse was typically a much slighter, daintier animal.

Read More Medieval warhorses no bigger than modern-day ponies, study finds (msn.com)

January 7th 2022

Winston Churchill’s parting message to Neville Chamberlain after failed Munich Agreement

Dominic Cummings makes new claim of party in No 10 garden in lockdownCelebrity tributes pour in for Black acting pioneer Sidney Poitier after death at 94

Neville Chamberlain served as Prime Minister from 1937 until May 1940. Best known for his foreign policy of appeasement, he played a crucial role in the Munich Agreement of September 1938, which handed the German-speaking Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia to Germany. Chamberlain famously declared “peace for our time” as he was photographed waving an agreement with Adolf Hitler in the air. The Munich Agreement is the subject of a new film ‘Munich: The Edge of War’, an adaptation of Robert Harris’ bestselling novel ‘Munich’.

Read More Winston Churchill’s parting message to Neville Chamberlain after failed Munich Agreement (msn.com)

January 4th 2022

Building The Titanic: The Story of The “Unsinkable Ship” | Our History – YouTube

November 28th 2021

London Underground: The untold story of the hidden tram network that ferried commuters across the city

Martin Elvery

Chemists could hold key to slashing NHS waiting lists, says pharmacists’ leaderVirgil Abloh death: Music world mourns ‘genius’ Off-White creator behind…

These days if you want to find a tram in London you have to go to Croydon – or to the London Transport Museum.

But back in the day, trams were the way to get around the capital.

Even before the London Underground was fully developed, Britain had the biggest tram network in the world.

Earlier this year, a key part of this network, the long abandoned Kingsway Tramway Subway, reopened to the public as the London Transport Museum offered tours around it.

We’ve uncovered the remarkable human story of the tunnel and what it has meant to Londoners.

The Amazing Escapes of Jack Sheppard

by Ben Johnson

Jack Sheppard was the 18th century’s most notorious robber and thief. His spectacular escapes from various prisons, including two from Newgate, made him the most glamorous rogue in London in the weeks before his dramatic execution.

Jack Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724) was born into a poor family in Spitalfields in London, an area notorious for highwaymen, villains and prostitutes in the early 18th century. He was apprenticed as a carpenter and by 1722, after 5 years of apprenticeship, he was already an accomplished craftsman, with less than a year of his training left.

Now 20 years old, he was a small man, 5’4″ tall and slightly built. His quick smile, charm and personality apparently made him popular in the taverns of Drury Lane, where he fell in with bad company and took up with a prostitute called Elizabeth Lyon, also known as ‘Edgworth Bess’.

He threw himself wholeheartedly into this shady underworld of drinking and whoring. Inevitably, his career as a carpenter suffered, and Sheppard took to stealing in order to boost his legitimate income. His first recorded crime was for petty shoplifting in spring 1723.

Read More The Amazing Escapes of Jack Sheppard (historic-uk.com)

The Stagecoach

by Ben Johnson

Originating in England in the 13th century, the stagecoach as we know it first appeared on England’s roads in the early 16th century. A stagecoach is so called because it travels in segments or “stages” of 10 to 15 miles. At a stage stop, usually a coaching inn, horses would be changed and travellers would have a meal or a drink, or stay overnight.

The first coaches were fairly crude and little better than covered wagons, generally drawn by four horses. Without suspension, these coaches could only travel at around 5 miles an hour on the rutted tracks and unmade roads of the time. During cold or wet weather, travel was often impossible. A writer of 1617 describes the “covered waggons in which passengers are carried to and fro; but this kind of journeying is very tedious, so that only women and people of inferior condition travel in this sort.”

Read More The Stagecoach (historic-uk.com)

Murderous Belief – July 6th 2021

HomeIslam Islam Has Massacred Over 669+ Million Non-Muslims Since 622AD

Donald Trump said Adolf Hitler ‘did a lot of good things’, new book claims

Donald Trump told his chief of staff that Adolf Hitler “did a lot of good things” as leader of Nazi Germany, according to a new book.

The former president was on a tour of Europe in 2018 when the retired four-star Marine general John Kelly gave him an impromptu history lesson to “remind the President which countries were on which side during the conflict” and “connect the dots from the First World War to the Second World War and all of Hitler’s atrocities”, it has been claimed.

But Michael Bender, author of the forthcoming book Frankly We Did Win This Election, alleges that Mr Trump insisted on outlining the positives of Germany’s economic recovery during the 1930s, saying: “Well, Hitler did a lot of good things.”

According to The Guardian, which has obtained a copy of the book, Mr Kelly was “stunned” but “pushed back again and argued that the German people would have been better off poor than subjected to the Nazi genocide”.

Islam Has Massacred Over 669+ Million Non-Muslims Since 622AD

In fact, no ideology has been as genocidal as Islam…By External Source -March 8, 2016104185065

In the total numbers we have updated over 80 million Christians killed by Muslims in 500 years in the Balkan states, Hungary, Ukraine, Russia.

Then we have India. The official estimate number of Muslim slaughters of Hindus is 80 million. However, Muslim historian Firistha (b. 1570) wrote (in either Tarikh-i Firishta or the Gulshan-i Ibrahim) that Muslims slaughtered over 400 million Hindus up to the peak of Islamic rule of India, bringing the Hindu population down from 600 mil to 200 million at the time.

With these new additions the Muslim genocide of non-Muslims since the birth of Mohammed would be over 669 million murders.

Islam: The Religion of Genocide

Perspective: Think the Spanish inquisition was bad?

- More people are killed by Islamists each year than in all 350 years of the Spanish Inquisition* combined.The Spanish inquisition (Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) from 1478 to 1834 was established due to muslim invasions. It was the war and battle to try and end Islamic infiltration, Arab fascism and conquest. It’s quite interesting how similar to muslims their methodology was. Was it habit by long association under muslim rule or a strategy?Note: The Spanish Inquisition was an answer to the multi-religious nature of Spanish society following the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim Moors.After invading in 711, large areas of the Iberian Peninsula were ruled by Muslims until 1250, when they were restricted to Granada, which fell in 1492. However, the Reconquista did not result in the total expulsion of Muslims from Spain, since they, along with the enslaved Jews, were tolerated by the ruling Christian elite. Large cities, especially Seville, Valladolid and Barcelona, had significant Jewish populations centered in Juderia. Muslims tried to take control throughout the entire country and expand into France to install an islamic state wherever they went.To expel the vicious Islamic parasite from the nation the Tribunal killed anyone and everyone who were suspected of being contaminated by Islam, even those enslaved by the muslims.The Inquisition not only hunted for Protestants and for false converts from Judaism among the conversos, but also searched for false or relapsed converts among the Moriscos [moors], forced converts from Islam. Many Moriscos were suspected of practising Islam in secret. They killed anyone suspected of being traitors or disguised moles. No one was spared.So successful was the enterprise in 1609, in the space of months, Spain was emptied of its Moriscos. Expelled were the Moriscos of Aragon, Murcia, Catalonia, Castile, Mancha and Extremadura.In other words, the Spanish inquisition saved the entire region from being taken over by Islamic rule. It was a brutal but quintessentially heroic act in history that saw the sacrifice of millions of people to exterminate Islam fully and completely from the land. It took them nearly 400 years. Imagine the sheer volume of muslims in the country for it to take almost four centuries to get rid of them.

Think the KKK has been bad since 1950?

Think the KKK was bad from 1865-1965?

Think the IRA’s terror campaign and the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland was bad?

Think capital punishment in the USA is barbaric?

It’s actually much worse than that: MORE PERSPECTIVE: Tears of Jihad

These figures are a rough estimate of the death of non-Muslims by the political act of jihad.

Africa

Thomas Sowell [Thomas Sowell, Race and Culture, BasicBooks, 1994, p. 188] estimates that 11 million slaves were shipped across the Atlantic and 14 million were sent to the Islamic nations of North Africa and the Middle East.

For every slave captured many others died.

Estimates of this collateral damage vary. The renowned missionary David Livingstone estimated that for every slave who reached a plantation, five others were killed in the initial raid or died of illness and privation on the forced march.

[Woman’s Presbyterian Board of Missions, David Livingstone, p. 62, 1888]

Those who were left behind were the very young, the weak, the sick and the old. These soon died since the main providers had been killed or enslaved.

So, for 25 million slaves delivered to the market, we have an estimated death of about 120 million people. Islam ran the wholesale slave trade in Africa.

120 million Africans

Christians

The number of Christians martyred by Islam is 9 million [David B. Barrett, Todd M. Johnson, World Christian Trends AD 30-AD 2200, William Carey Library, 2001, p. 230, table 4-10] .

A rough estimate by Raphael Moore in History of Asia Minor is that another 50 million died in wars by jihad.

So counting the million African Christians killed in the 20th century we have:

59 million Christians in Asia Minor

80 million Christians killed by Muslims during 500 years in the Balkan states, Hungary, Ukraine, Russia.

[This calculation does not include the Arab biological warfare of the middle ages where enslaved and infected Jews, riddled with plague, were dumped across Europe in regions that had no Jewish origin or settlers. They carried the disease from the brutal Arab slave trade and were part of the enslaved blacks, Christians and Jews who managed to survive by paying jizya. These diseased people were then spread into Europe during muslim efforts to conquer the Italian coast (Venice), Greece, Spain, etc. The plague ended up killing half of the entire population of Europe]

Hindus

Koenard Elst in Negationism in India gives an estimate of 80 million Hindus killed in the total jihad against India. [Koenard Elst, Negationism in India, Voice of India, New Delhi, 2002, pg. 34.]

The country of India today is only half the size of ancient India, due to jihad. The mountains near India are called the Hindu Kush, meaning the “funeral pyre of the Hindus.”

80 million Hindus + adjusted 320 million = 400 million Hindus

[UPDATE: According to reports from the 1899 in a statement made by Indian religious leader Swami Vivekananda quoting Muslim historian Firistha, Muslims slaughtered over 400 million Hindus during an 800 year Muslim rule, bringing a population down from 600 mil to 200 million at the time. Firishta wrote the Tarikh-i Firishta and the Gulshan-i Ibrahim. If Muslims indeed slaughtered over 400 million people in India, the Muslim genocide around the world would exceed 890 million victims.

“When the Mohammedans first came we were said – I think on the authority of Ferishta, the oldest Mohammedan historian – to have been six hundred millions of Hindus. Now we are about two hundred millions.

— An interview of Swami Vivekananda, published in Prabuddha Bharat. April, 1899 and compiled under heading ‘On the Bounds of Hinduism’.]

400 million Hindus

Buddhists

Buddhists do not keep up with the history of war. Keep in mind that in jihad only Christians and Jews were allowed to survive as dhimmis (servants to Islam); everyone else had to convert or die.

Jihad killed the Buddhists in Turkey, Afghanistan, along the Silk Route, and in India.

The total is roughly 10 million. [David B. Barrett, Todd M. Johnson, World Christian Trends AD 30-AD 2200, William Carey Library, 2001, p. 230, table 4-1.]

10 million Buddhists

Jews

Oddly enough there were not enough Jews killed in jihad to significantly affect the totals of the Great Annihilation. The jihad in Arabia was 100 percent effective, but the numbers were in the thousands, not millions.

After that, the Jews submitted and became the dhimmis (servants and second class citizens) of Islam and did not have geographic political power.

This gives a rough estimate of 669+ million killed by jihad.

Missing Data

Persians.

Muslims invaded and occupied the peace-loving Persians, the followers of Zorohaustra.

Christians in the Middle East.

Chinese during the mongul invasions.

Plus Muslims have slaughtered 11 million other Muslims since 1948 in addition to the 669million+ non-Muslims they have murdered over the centuries. How many Muslims they have murdered over 1,400 years is unknown.

590,000,000: that’s way more than stalin, hitler, mao, pol pot, idi amin (a sunni muslim), and the rest of the 20th century’s genocidal socialists! And it doesn’t stop there. The killing by muslims around the world continues to this day.

- For good reasons, the left loves to hate the spanish inquisition, the kkk, and there are even good arguments against capital punishment in the usa (though i support it!).

- The left has no problem calling the spanish inquisition and the kkk and capital punishment barbaric.

- So why don’t they criticize islam – which is demonstrably worse than all three combined!?!?

- In fact, no ideology has been as genocidal as islam…

- Nor has any ideology been so bloodthirsty for so long. For centuries…

- Nor has any ideology ever been as anti-liberty, anti-democracy – or as anti-woman.

It’s time it was stopped. For good.

Allegation that people are killed for leaving Islam

BY AL5LAS · AUGUST 2, 2012

For the attention of non-muslims.

If someone wants to leave Islam, they get killed. YES or NO??

Regarding the apostasy issue, its not as simple as a YES or NO. Its not as black an white as that, regardless of how people may invisage it.

You believe in freedom of expression and free speech an all that, fair dos. People believe in different things. You cant force us to follow what you believe and i cant force you to believe what i believe. We believe in God and feel everything should be done according to his law, which is contained in his final revelation.

This law would be Islamic law, and the issue of apostacy would come under this area. The only way the law regarding apostacy could come into practice is if the individuals concerned are living under an Islamic state. In an Islamic state, people live under the law of the land. Just as we follow English law under her majesty’s pleasure in England, and everyone else follows the law of their own country. It would just happen to be that in an Islamic state, the country would have their own laws. Nout wrong with that is their, you wont prevent people from having their own laws in their own countries now would you lad.

Now if someone in an Islamic state wants to leave Islam, they will do. It is literally a personal choice and once they have made their mind up thats the end of it. However In that Islamic if someone openly declares that they are no longer a Muslim and by doing so cause unrest and seek to cause harm to the state, then this person can be dealt with by either being asked to leave the state or by being executed.

When someone enters into Islam they not only devote their personal spiritual self to God, but in the case of the one in the Islamic state they also devote themselves to the political structure laid down by Gods law. When we look at apostacy here, we have to look at it in the correct historical context and with the right conditions. Its not just a matter of YES and NO.

From the western perspective religion has no place to play in the legal system. A person is free to follow a religion or not, this is why to you the idea of someone being executed for leaving their religion seems quite absurd. However, we should keep in mind that when capital punishment was abolished for murder back in 1965, it was still retained for treason and piracy with violence. Infact it was also the legal punishment for setting fire to her majesty’s ships all the way up till 1971! Now thats absurd.

This principle of treason still exists today in most countries, where treason is considered to be rebellious against the state such as where state secrets are given to some other country, people are executed. Remember now this is execution for material information.

Now when we look at the Islamic perspective, religion is viewed differently then it is in the west. In Islam, the religion is the state. There is no seperation of powers in that sense, the state an Islam are one. The state is governed by the religious principles, so rebellion against the state is rebellion against the religion. Apostacy in an Islamic state amounts to a rejection of the law and the order of that society and as such it is considered as an act of treason.

As i mentioned, a person who abandons the faith personally and feels they no longer want to live under the law of the land and the system is free to leave and do as they please. Islam does not allow or prescribe that these people should be hunted down like Salman Rushdie and killed simply because they chose to leave Islam. The law of apostacy only really deals with people who within the Islamic state openly reject the principles and laws of the state and those who undermine the social islamic system of the state as a whole.

Yes there is no compulsion of religion within Islam; compulsion in joining Islam. But once someone becomes a Muslim, they are obliged to stick with Islam in that this is a serious commitment. You cant compare being part of a religion with anything else, which is the common mistake people make. Its not like buying a new pair of trainers, or picking somewhere to eat out. The whole point is that you believe this is the true religion of God, and as such this is the purpose to your life – something you are very serious about.

You also have to look at the motives behind the entire law of apostacy in Islam. It was first implemented at the time of the prophet in Medina when opponents of Islam were intentionally joining Islam and then leaving it within days and even hours in order to shake the faith of the Muslims and to undermine the order of law. They were playing with the religion to cause confusion amongst other new muslims and weaker members of society. This law aims to prevent any such tactic being employed within an Islamic state.

The death penalty is for those who co-operate with individuals at war with the Islamic state, or those who gather people to fight against the state. This is the real practical application of the law in Islam. In Islam we dont have inqusition courts set up to track an test peoples different levels of faith. What people do personally is their own choice. The death penalty only becomes an issue in the circumstances i have already mentioned.

Where a person openly challenges the law and order of the state and undermines the social system by apostating in a rebellious and hostile fashion, if they get caught and are brought before court – they are still afforded the opportunity to retract their statement and take it back. If they do retract their statement, they are not executed and are free to go. This just goes to show the level of justice which is afforded by Islam even to people who seek to cause unrest. It also shows the type of people we are dealing with, not your average joe. Joe would simply retract his statement and not get executed, however the one who clearly has intention of causing unrest and is even unwilling to take the opportunity of leniancy and pardon – this is the type of person who will clearly be harmful to the state an thus execution is permissable.

So in short, western civilisations have and will execute its citizens for giving away state secrets – something which is mere material. Even if they beg for forgiveness and repent, they will be punished. Islamic law will not execute people for the same purpose. However they will execute them for something which is far more serious; rebellion against God. May not seem much to you, but if a muslim lives in an Islamic state and makes that choice to be muslim and abide by the law of the state, it is a very serious matter. In Islam, this type of rebellion is far greater then the rebellion against the individual or the state.

It is not for the Islamic state to simply declare someone as an apostate or for people on the street to call for someone to be killed. Their are courts of law where the matter is looked into with all the evidence presented, the individuals have to be questioned and they have the right to defend themselves.

To make it clearer and to answer a question non muslims often ask:

“So you do believe someone should be murdered if they leave your faith?”

NO i dont. I dont believe another human should be murdered because of their religious beliefs. I believe in everything i have written above, and if you need further clarification then please read it again, or message me

Related content:

- Who are the real terrorists?

- Allegation that Muhammad was racist

- Is it Islam??

- Fabrication of hadith

- Meaning of Islam: Myths, stereotypes hide the truth

White Ship – Posted July 4th 2021

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to navigationJump to searchThis article is about the twelfth-century vessel. For fictional tales with this title, see The White Ship (disambiguation).

| The White Ship sinking | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Blanche-Nef |

| Out of service | 25 November 1120 |

| Fate | Struck a submerged rock off Barfleur, Normandy |

| Status | Wreck |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Sailing ship |

| Installed power | Square Sails |

| Propulsion | Wind and oars |

The White Ship (French: la Blanche-Nef; Medieval Latin: Candida navis) was a vessel that sank in the English Channel near the Normandy coast off Barfleur, on 25 November 1120. Only one of approximately 300 people aboard survived, a butcher from Rouen.[1] Those who drowned included William Adelin, the only in-wedlock son and heir of King Henry I of England, his half-sister Matilda, his half-brother Richard, Richard d’Avranches, 2nd Earl of Chester, and Geoffrey Ridel. William Adelin’s death led to a succession crisis and a period of civil war in England from 1135–53 known as the Anarchy.

Contents

Shipwreck[edit]

The White Ship was a newly refitted vessel captained by Thomas FitzStephen (Thomas filz Estienne), whose father Stephen FitzAirard (Estienne filz Airard) had been captain of the ship Mora for William the Conqueror when he invaded England in 1066.[2] Thomas offered his ship to Henry I of England to return to England from Barfleur in Normandy.[3] Henry had already made other arrangements, but allowed many in his retinue to take the White Ship, including his heir, William Adelin, his out-of-wedlock son Richard of Lincoln, his out-of-wedlock daughter Matilda FitzRoy, Countess of Perche, and many other nobles.[3]

According to chronicler Orderic Vitalis, the crew asked William Adelin for wine and he supplied it to them in great abundance.[3] By the time the ship was ready to leave there were about 300 people on board, although some, including the future king Stephen of Blois, had disembarked due to the excessive binge drinking before the ship sailed.[4]

The ship’s captain, Thomas FitzStephen, was ordered by the revellers to overtake the king’s ship, which had already sailed.[4] The White Ship was fast, of the best construction and had recently been fitted with new materials, which made the captain and crew confident they could reach England first. But when it set off in the dark, its port side struck a submerged rock called Quillebœuf, and the ship quickly capsized.[4]

William Adelin got into a small boat and could have escaped but turned back to try to rescue his half-sister, Matilda, when he heard her cries for help. His boat was swamped by others trying to save themselves, and William drowned along with them.[4] According to Orderic Vitalis, Berold (Beroldus or Berout), a butcher from Rouen, was the sole survivor of the shipwreck by clinging to the rock. The chronicler further wrote that when Thomas FitzStephen came to the surface after the sinking and learned that William Adelin had not survived, he let himself drown rather than face the King.[5]

One legend holds that the ship was doomed because priests were not allowed to board it and bless it with holy water in the customary manner.[6][a] For a complete list of those who did or did not travel on the White Ship, see Victims of the White Ship disaster.

Repercussions[edit]

Henry I and the sinking White Ship.Main article: The Anarchy

A direct result of William Adelin’s death was the period known as the Anarchy. The White Ship disaster had left Henry I with only one in-wedlock child, a second daughter named Matilda. Although Henry I had forced his barons to swear an oath to support Matilda as his heir on several occasions, a woman had never ruled in England in her own right. Matilda was also unpopular because she was married to Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, a traditional enemy of England’s Norman nobles. Upon Henry’s death in 1135, the English barons were reluctant to accept Matilda as queen regnant.

One of Henry I’s male relatives, Stephen of Blois, the king’s nephew by his sister Adela, usurped Matilda as well as his older brothers William and Theobald to become king. Stephen had allegedly planned to travel on the White Ship but had disembarked just before it sailed;[3] Orderic Vitalis attributes this to a sudden bout of diarrhoea.[citation needed]

After Henry I’s death, Matilda and her husband Geoffrey of Anjou, the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty, launched a long and devastating war against Stephen and his allies for control of the English throne. The Anarchy dragged from 1135 to 1153 with devastating effect, especially in southern England.

Contemporary historian William of Malmesbury wrote:

No ship that ever sailed brought England such disaster, none was so well known the wide world over. There perished then with William the king’s other son Richard, born to him before his accession by a woman of the country, a high-spirited youth, whose devotion had earned his father’s love; Richard earl of Chester and his brother Othuel, the guardian and tutor of the king’s son; the king’s daughter the countess of Perche, and his niece, Theobald’s sister, the countess of Chester; besides all the choicest knights and chaplains of the court, and the nobles’ sons who were candidates for knighthood, for they had hastened to from all sides to join him, as I have said, expecting no small gain in reputation if they could show the king’s son some sport or do him some service.[7]

Historical fiction[edit]

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Reference to the sinking of the White Ship is made in Ken Follett‘s novel The Pillars of the Earth (1989) and its later game adaptation. The ship’s sinking sets the stage for the entire background of the story, which is based on the subsequent civil war between Matilda (referred to as Maud in the novel) and Stephen. In Follett’s novel, it is implied that the ship may have been sabotaged; this implication is seen in the TV adaptation – even going so far as to show William Adelin assassinated whilst on a lifeboat – and the video game adaptation.

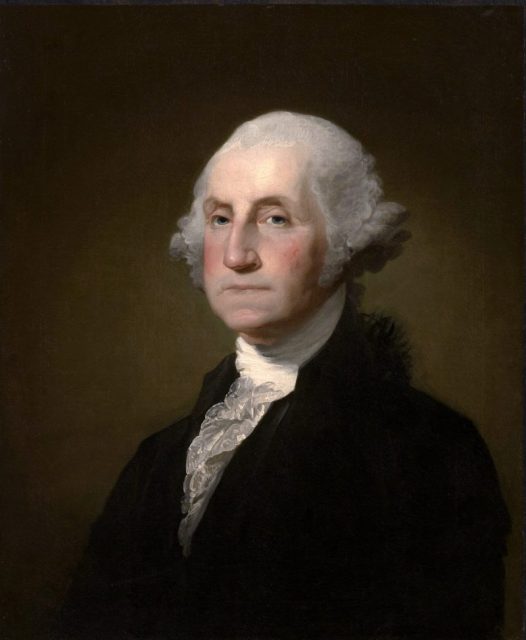

Christopher Columbus[a] (/kəˈlʌmbəs/;[3] born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was an Italian[b] explorer and navigator who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and colonization of the Americas. His expeditions, sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, were the first European contact with the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

Columbus was looking to find a westward sea route to the East Indies but instead landed in what is now known as the West Indies. His voyages ultimately resulted in lasting contact and colonization of European countries in the Americas. Prior to Columbus’s voyages, the people (including Columbus himself) who were living in the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa were unaware that the North and South American continents even existed.

The name Christopher Columbus is the Anglicisation of the Latin Christophorus Columbus. Scholars generally agree that Columbus was born in the Republic of Genoa and spoke a dialect of Ligurian as his first language. He went to sea at a young age and travelled widely, as far north as the British Isles and as far south as what is now Ghana. He married Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo and was based in Lisbon for several years, but later took a Castilian mistress; he had one son with each woman. Though largely self-educated, Columbus was widely read in geography, astronomy, and history. He formulated a plan to seek a western sea passage to the East Indies, hoping to profit from the lucrative spice trade. Following Columbus’s persistent lobbying to multiple kingdoms, Catholic monarchs Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand II agreed to sponsor a journey west. Columbus left Castile in August 1492 with three ships, and made landfall in the Americas on 12 October (ending the period of human habitation in the Americas now referred to as the pre-Columbian era). His landing place was an island in the Bahamas, known by its native inhabitants as Guanahani. Columbus subsequently visited the islands now known as Cuba and Hispaniola, establishing a colony in what is now Haiti. Columbus returned to Castile in early 1493, bringing a number of captured natives with him. Word of his voyages soon spread throughout Europe.

Columbus made three further voyages to the Americas, exploring the Lesser Antilles in 1493, Trinidad and the northern coast of South America in 1498, and the eastern coast of Central America in 1502. Many of the names he gave to geographical features—particularly islands—are still in use. He also gave the name indios (“Indians”) to the indigenous peoples he encountered. The extent to which he was aware that the Americas were a wholly separate landmass is uncertain; he never clearly renounced his belief that he had reached the Far East. As a colonial governor, Columbus was accused by his contemporaries of significant brutality and was soon removed from the post. Columbus’s strained relationship with the Crown of Castile and its appointed colonial administrators in America led to his arrest and removal from Hispaniola in 1500, and later to protracted litigation over the benefits that he and his heirs claimed were owed to them by the crown. Columbus’s expeditions inaugurated a period of exploration, conquest, and colonization that lasted for centuries, helping create the modern Western world. The transfers between the Old World and New World that followed his first voyage are known as the Columbian exchange.

Columbus was widely venerated in the centuries after his death, but public perception has fractured in recent decades as scholars give greater attention to the harm committed under his governance, particularly the near-extermination of Hispaniola’s indigenous Taíno population from mistreatment and European diseases, as well as their enslavement. Proponents of the Black Legend theory of history claim that Columbus has been unfairly maligned as part of a wider anti-Catholic sentiment. Many places in the Western Hemisphere bear his name, including the country of Colombia, the District of Columbia, and the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Quest for Asia

- 3Voyages

- 4Later life, illness, and death

- 5Location of remains

- 6Commemoration

- 7Legacy

- 8Physical appearance

- 9See also

- 10Notes

- 11References

- 12Further reading

- 13External links

Early life

Further information on Columbus’s birthplace and family background: Origin theories of Christopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus House in Genoa, a 18-century reconstruction of the original Columbus’ house likely destroyed during the 1684 bombardment, and rebuilt on the basis of its ruins.[6][7]

Columbus’s early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the Republic of Genoa between 25 August and 31 October 1451.[5] His father was Domenico Colombo,[8] a wool weaver who worked both in Genoa and Savona and who also owned a cheese stand at which young Christopher worked as a helper. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa.[8][c] He had three brothers—Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo (also called Diego),[2] as well as a sister named Bianchinetta.[9] His brother Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.[10]

His native language is presumed to have been a Genoese dialect although Columbus never wrote in that language. His name in the 16th-century Genoese language would have been Cristoffa[11] Corombo[12] (Ligurian pronunciation: [kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu]).[13][14] His name in Italian is Cristoforo Colombo, and in Spanish Cristóbal Colón.[8]

In one of his writings, he says he went to sea at the age of 10. In 1470, the Columbus family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Christopher was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Some modern authors have argued that he was not from Genoa but, instead, from the Aragon region of Spain[15] or from Portugal.[16] These competing hypotheses have generally been discounted by mainstream scholars.[17][18]

In 1473, Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the wealthy Spinola, Centurione, and Di Negro families of Genoa. Later, he made a trip to Chios, an Aegean island then ruled by Genoa.[19] In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably docked in Bristol, England,[20] and Galway, Ireland. He may have also gone to Iceland in 1477.[8][21][22] It is known that in the autumn of 1477, he sailed on a Portuguese ship from Galway to Lisbon, where he found his brother Bartolomeo, and they continued trading for the Centurione family. Columbus based himself in Lisbon from 1477 to 1485. He married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, daughter of the Porto Santo governor and Portuguese nobleman of Lombard origin Bartolomeu Perestrello.[23]

In 1479 or 1480, Columbus’s son Diego was born. Between 1482 and 1485, Columbus traded along the coasts of West Africa, reaching the Portuguese trading post of Elmina at the Guinea coast (in present-day Ghana).[24] Before 1484, Columbus returned to Porto Santo to find that his wife had died.[25] He returned to Portugal to settle her estate and take his son Diego with him.[26] He left Portugal for Castile in 1485, where he found a mistress in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named Beatriz Enríquez de Arana.[27] It is likely that Beatriz met Columbus when he was in Córdoba, a gathering site of many Genoese merchants and where the court of the Catholic Monarchs was located at intervals. Beatriz, unmarried at the time, gave birth to Columbus’s natural son, Fernando Columbus in July 1488, named for the monarch of Aragon. Columbus recognized the boy as his offspring. Columbus entrusted his older, legitimate son Diego to take care of Beatriz and pay the pension set aside for her following his death, but Diego was negligent in his duties.[28]Columbus’s copy of The Travels of Marco Polo, with his handwritten notes in Latin written on the margins

Ambitious, Columbus eventually learned Latin, Portuguese, and Castilian. He read widely about astronomy, geography, and history, including the works of Claudius Ptolemy, Pierre Cardinal d’Ailly‘s Imago Mundi, the travels of Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville, Pliny‘s Natural History, and Pope Pius II‘s Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum. According to historian Edmund Morgan,

Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong …[29]

Did Black People Own Slaves? Posted July 2nd 2021

100 Amazing Facts About the Negro: Yes — but why they did and how many they owned will surprise you.

- By: Henry Louis Gates Jr. |

Nicolas Augustin Metoyer of Louisiana owned 13 slaves in 1830. He and his 12 family members collectively owned 215 slaves.

Editor’s note:For those who are wondering about the retro title of this black history series, please take a moment to learn about historianJoel A. Rogers, author of the 1934 book100 Amazing Facts About the Negro With Complete Proof, to whom these “amazing facts” are an homage.

(The Root) — 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro No. 21: Did black people own slaves? If so, why?

One of the most vexing questions in African-American history is whether free African Americans themselves owned slaves. The short answer to this question, as you might suspect, is yes, of course; some free black people in this country bought and sold other black people, and did so at least since 1654, continuing to do so right through the Civil War. For me, the really fascinating questions about black slave-owning are how many black “masters” were involved, how many slaves did they own and why did they own slaves?

The answers to these questions are complex, and historians have been arguing for some time over whether free blacks purchased family members as slaves in order to protect them — motivated, on the one hand, by benevolence and philanthropy, as historian Carter G. Woodson put it, or whether, on the other hand, they purchased other black people “as an act of exploitation,” primarily to exploit their free labor for profit, just as white slave owners did. The evidence shows that, unfortunately, both things are true. The great African-American historian, John Hope Franklin, states this clearly: “The majority of Negro owners of slaves had some personal interest in their property.” But, he admits, “There were instances, however, in which free Negroes had a real economic interest in the institution of slavery and held slaves in order to improve their economic status.”

In a fascinating essay reviewing this controversy, R. Halliburton shows that free black people have owned slaves “in each of the thirteen original states and later in every state that countenanced slavery,” at least since Anthony Johnson and his wife Mary went to court in Virginia in 1654 to obtain the services of their indentured servant, a black man, John Castor, for life.

And for a time, free black people could even “own” the services of white indentured servants in Virginia as well. Free blacks owned slaves in Boston by 1724 and in Connecticut by 1783; by 1790, 48 black people in Maryland owned 143 slaves. One particularly notorious black Maryland farmer named Nat Butler “regularly purchased and sold Negroes for the Southern trade,” Halliburton wrote.

Perhaps the most insidious or desperate attempt to defend the right of black people to own slaves was the statement made on the eve of the Civil War by a group of free people of color in New Orleans, offering their services to the Confederacy, in part because they were fearful for their own enslavement: “The free colored population [native] of Louisiana … own slaves, and they are dearly attached to their native land … and they are ready to shed their blood for her defense. They have no sympathy for abolitionism; no love for the North, but they have plenty for Louisiana … They will fight for her in 1861 as they fought [to defend New Orleans from the British] in 1814-1815.”

These guys were, to put it bluntly, opportunists par excellence: As Noah Andre Trudeau and James G. Hollandsworth Jr. explain, once the war broke out, some of these same black men formed 14 companies of a militia composed of 440 men and were organized by the governor in May 1861 into “the Native Guards, Louisiana,” swearing to fight to defend the Confederacy. Although given no combat role, the Guards — reaching a peak of 1,000 volunteers — became the first Civil War unit to appoint black officers.

When New Orleans fell in late April 1862 to the Union, about 10 percent of these men, not missing a beat, now formed the Native Guard/Corps d’Afrique to defend the Union. Joel A. Rogers noted this phenomenon in his 100 Amazing Facts: “The Negro slave-holders, like the white ones, fought to keep their chattels in the Civil War.” Rogers also notes that some black men, including those in New Orleans at the outbreak of the War, “fought to perpetuate slavery.”

How Many Slaves Did Blacks Own?

So what do the actual numbers of black slave owners and their slaves tell us? In 1830, the year most carefully studied by Carter G. Woodson, about 13.7 percent (319,599) of the black population was free. Of these, 3,776 free Negroes owned 12,907 slaves, out of a total of 2,009,043 slaves owned in the entire United States, so the numbers of slaves owned by black people over all was quite small by comparison with the number owned by white people. In his essay, ” ‘The Known World’ of Free Black Slaveholders,” Thomas J. Pressly, using Woodson’s statistics, calculated that 54 (or about 1 percent) of these black slave owners in 1830 owned between 20 and 84 slaves; 172 (about 4 percent) owned between 10 to 19 slaves; and 3,550 (about 94 percent) each owned between 1 and 9 slaves. Crucially, 42 percent owned just one slave. Pressly also shows that the percentage of free black slave owners as the total number of free black heads of families was quite high in several states, namely 43 percent in South Carolina, 40 percent in Louisiana, 26 percent in Mississippi, 25 percent in Alabama and 20 percent in Georgia. So why did these free black people own these slaves?

It is reasonable to assume that the 42 percent of the free black slave owners who owned just one slave probably owned a family member to protect that person, as did many of the other black slave owners who owned only slightly larger numbers of slaves. As Woodson put it in 1924’s Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830, “The census records show that the majority of the Negro owners of slaves were such from the point of view of philanthropy. In many instances the husband purchased the wife or vice versa … Slaves of Negroes were in some cases the children of a free father who had purchased his wife. If he did not thereafter emancipate the mother, as so many such husbands failed to do, his own children were born his slaves and were thus reported to the numerators.”

Moreover, Woodson explains, “Benevolent Negroes often purchased slaves to make their lot easier by granting them their freedom for a nominal sum, or by permitting them to work it out on liberal terms.” In other words, these black slave-owners, the clear majority, cleverly used the system of slavery to protect their loved ones. That’s the good news.

But not all did, and that is the bad news. Halliburton concludes, after examining the evidence, that “it would be a serious mistake to automatically assume that free blacks owned their spouse or children only for benevolent purposes.” Woodson himself notes that a “small number of slaves, however, does not always signify benevolence on the part of the owner.” And John Hope Franklin notes that in North Carolina, “Without doubt, there were those who possessed slaves for the purpose of advancing their [own] well-being … these Negro slaveholders were more interested in making their farms or carpenter-shops ‘pay’ than they were in treating their slaves humanely.” For these black slaveholders, he concludes, “there was some effort to conform to the pattern established by the dominant slaveholding group within the State in the effort to elevate themselves to a position of respect and privilege.” In other words, most black slave owners probably owned family members to protect them, but far too many turned to slavery to exploit the labor of other black people for profit.

Who Were These Black Slave Owners?

If we were compiling a “Rogues Gallery of Black History,” the following free black slaveholders would be in it: John Carruthers Stanly — born a slave in Craven County, N.C., the son of an Igbo mother and her master, John Wright Stanly — became an extraordinarily successful barber and speculator in real estate in New Bern. As Loren Schweninger points out in Black Property Owners in the South, 1790-1915, by the early 1820s, Stanly owned three plantations and 163 slaves, and even hired threewhite overseers to manage his property! He fathered six children with a slave woman named Kitty, and he eventually freed them. Stanly lost his estate when a loan for $14,962 he had co-signed with his white half brother, John, came due. After his brother’s stroke, the loan was Stanly’s sole responsibility, and he was unable to pay it.

William Ellison’s fascinating story is told by Michael Johnson and James L. Roark in their book, Black Masters: A Free Family of Color in the Old South. At his death on the eve of the Civil War, Ellison was wealthier than nine out of 10 white people in South Carolina. He was born in 1790 as a slave on a plantation in the Fairfield District of the state, far up country from Charleston. In 1816, at the age of 26, he bought his own freedom, and soon bought his wife and their child. In 1822, he opened his own cotton gin, and soon became quite wealthy. By his death in 1860, he owned 900 acres of land and 63 slaves. Not one of his slaves was allowed to purchase his or her own freedom.

Louisiana, as we have seen, was its own bizarre world of color, class, caste and slavery.

By 1830, in Louisiana, several black people there owned a large number of slaves, including the following: In Pointe Coupee Parish alone, Sophie Delhonde owned 38 slaves; Lefroix Decuire owned 59 slaves; Antoine Decuire owned 70 slaves; Leandre Severin owned 60 slaves; and Victor Duperon owned 10. In St. John the Baptist Parish, Victoire Deslondes owned 52 slaves; in Plaquemine Brule, Martin Donatto owned 75 slaves; in Bayou Teche, Jean B. Muillion owned 52 slaves; Martin Lenormand in St. Martin Parish owned 44 slaves; Verret Polen in West Baton Rouge Parish owned 69 slaves; Francis Jerod in Washita Parish owned 33 slaves; and Cecee McCarty in the Upper Suburbs of New Orleans owned 32 slaves. Incredibly, the 13 members of the Metoyer family in Natchitoches Parish — including Nicolas Augustin Metoyer, pictured — collectively owned 215 slaves.

Antoine Dubuclet and his wife Claire Pollard owned more than 70 slaves in Iberville Parish when they married. According to Thomas Clarkin, by 1864, in the midst of the Civil War, they owned 100 slaves, worth $94,700. During Reconstruction, he became the state’s first black treasurer, serving between 1868 and 1878.

Andrew Durnford was a sugar planter and a physician who owned the St. Rosalie plantation, 33 miles south of New Orleans. In the late 1820s, David O. Whitten tells us, he paid $7,000 for seven male slaves, five females and two children. He traveled all the way to Virginia in the 1830s and purchased 24 more. Eventually, he would own 77 slaves. When a fellow Creole slave owner liberated 85 of his slaves and shipped them off to Liberia, Durnford commented that he couldn’t do that, because “self interest is too strongly rooted in the bosom of all that breathes the American atmosphere.”

It would be a mistake to think that large black slaveholders were only men. In 1830, in Louisiana, the aforementioned Madame Antoine Dublucet owned 44 slaves, and Madame Ciprien Ricard owned 35 slaves, Louise Divivier owned 17 slaves, Genevieve Rigobert owned 16 slaves and Rose Lanoix and Caroline Miller both owned 13 slaves, while over in Georgia, Betsey Perry owned 25 slaves. According to Johnson and Roark, the wealthiest black person in Charleston, S.C., in 1860 was Maria Weston, who owned 14 slaves and property valued at more than $40,000, at a time when the average white man earned about $100 a year. (The city’s largest black slaveholders, though, were Justus Angel and Mistress L. Horry, both of whom owned 84 slaves.)

In Savannah, Ga., between 1823 and 1828, according to Betty Wood‘s Gender, Race, and Rank in a Revolutionary Age, Hannah Leion owned nine slaves, while the largest slaveholder in 1860 was Ciprien Ricard, who had a sugarcane plantation in Louisiana and owned 152 slaves with her son, Pierre — many more that the 35 she owned in 1830. According to economic historian Stanley Engerman, “In Charleston, South Carolina about 42 percent of free blacks owned slaves in 1850, and about 64 percent of these slaveholders were women.” Greed, in other words, was gender-blind.

Why They Owned Slaves

These men and women, from William Stanly to Madame Ciprien Ricard, were among the largest free Negro slaveholders, and their motivations were neither benevolent nor philanthropic. One would be hard-pressed to account for their ownership of such large numbers of slaves except as avaricious, rapacious, acquisitive and predatory.

But lest we romanticize all of those small black slave owners who ostensibly purchased family members only for humanitarian reasons, even in these cases the evidence can be problematic. Halliburton, citing examples from an essay in the North American Review by Calvin Wilson in 1905, presents some hair-raising challenges to the idea that black people who owned their own family members always treated them well:

A free black in Trimble County, Kentucky, ” … sold his own son and daughter South, one for $1,000, the other for $1,200.” … A Maryland father sold his slave children in order to purchase his wife. A Columbus, Georgia, black woman — Dilsey Pope — owned her husband. “He offended her in some way and she sold him … ” Fanny Canady of Louisville, Kentucky, owned her husband Jim — a drunken cobbler — whom she threatened to “sell down the river.” At New Bern, North Carolina, a free black wife and son purchased their slave husband-father. When the newly bought father criticized his son, the son sold him to a slave trader. The son boasted afterward that “the old man had gone to the corn fields about New Orleans where they might learn him some manners.”

Carter Woodson, too, tells us that some of the husbands who purchased their spouses “were not anxious to liberate their wives immediately. They considered it advisable to put them on probation for a few years, and if they did not find them satisfactory they would sell their wives as other slave holders disposed of Negroes.” He then relates the example of a black man, a shoemaker in Charleston, S.C., who purchased his wife for $700. But “on finding her hard to please, he sold her a few months thereafter for $750, gaining $50 by the transaction.”

Most of us will find the news that some black people bought and sold other black people for profit quite distressing, as well we should. But given the long history of class divisions in the black community, whichMartin R. Delany as early as the 1850s described as “a nation within a nation,” and given the role of African elites in the long history of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, perhaps we should not be surprised that we can find examples throughout black history of just about every sort of human behavior, from the most noble to the most heinous, that we find in any other people’s history.

The good news, scholars agree, is that by 1860 the number of free blacks owning slaves had markedly decreased from 1830. In fact, Loren Schweninger concludes that by the eve of the Civil War, “the phenomenon of free blacks owning slaves had nearly disappeared” in the Upper South, even if it had not in places such as Louisiana in the Lower South. Nevertheless, it is a very sad aspect of African-American history that slavery sometimes could be a colorblind affair, and that the evil business of owning another human being could manifest itself in both males and females, and in black as well as white.

As always, you can find more “Amazing Facts About the Negro” on The Root, and check back each week as we count to 100.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and the director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard University. He is also the editor-in-chief of The Root. Follow him on Twitter.

Re writing History , Déjà vu by Robert Cook May 4th 2021

Déjà vu is associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. This experience is a neurological anomaly related to epileptic electrical discharge in the brain, creating a strong sensation that an event or experience currently being experienced has already been experienced in the past.

Napoleon set out to build an empire, his aristocratic in bred rivals combined to destroy him , both sides using their enslaved white minions to do the fighting and dying for them. The Duke of Wellington , who went on to order The Peterloo Massacre, called his Waterloo troops ‘the scum of the earth.’

The elite still considers the white working classes scum. They would never permit these people a WLM version of history as they do their BLM protegees who serve their purpose. Whites are undergoing a process of cultural and ethnic genocide to make room for the BAME colonisation of Europe.

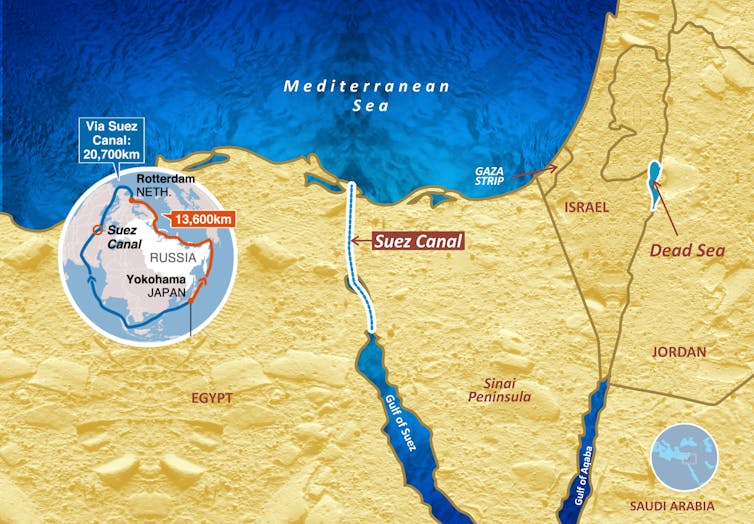

Suez canal: what the ‘ditch’ meant to the British empire in the 19th century Posted April 12th 2021

March 31, 2021 5.08pm BST

Author

- Jonathan Parry Professor of Modern British History Director of Studies in History and Politics, Pembroke College, University of Cambridge

Disclosure statement

Jon Parry received funding from the Leverhulme Trust for the research for a book on Britain and the Middle East, which is scheduled for publication in early 2022.

Partners

University of Cambridge provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

We believe in the free flow of information

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

The week-long blockage of the Suez canal by the Ever Given container ship has reminded us that the canal, though immensely important to the world’s commerce, is also very vulnerable.

Since its completion in 1869, it has symbolised global interconnectedness. But it has also demonstrated how fears, rivalries and bottlenecks have threatened to obstruct that connectedness. Its narrowness has generated periodic panic and neurosis in the countries which rely on it most – often meaning Britain.

In 1882, Britain invaded and occupied Egypt, from an anxiety to secure the imperial link with India which seemed imperilled by Egyptian disorder. Its troops did not leave until 1956, after the debacle of the Suez crisis of that year.

Though the waterway came to be hugely symbolic for the British, it is too simple to see it as the only driver of British imperialism. It was merely the third stage of the transit arrangements across Egypt forged during the 19th century: to create effective communication with India, British entrepreneurs, helped by the state, pioneered a river and road connection in the 1830s between Alexandria and Suez, and then a railway in the 1850s. From 1840, these linked with P&O steamers on both sides.

Disinformation is dangerous. We fight it with facts and expertise

In 1854, £6.4 million of currency was transferred across Egypt, as well as nearly 4,000 passengers. In 1851, the Royal Navy sent two warships to Alexandria to give “moral support” to the Egyptian viceroy’s approval of the railway, which was opposed by his nominal overlord, the sultan of the Ottoman empire.

In 1855, Lord Clarendon, the British foreign secretary, made clear to the sultan, the viceroy, and Napoleon III, the French emperor, that while Britain sought no territorial advantage in Egypt, it insisted on a “thoroughfare, free and unmolested”. The importance of this to Britain can be seen by the fact that, in 1857, 5,000 troops were sent through Egypt to quell the Indian mutiny.

In the 1850s, even Napoleon III accepted Britain’s primacy in Egypt, because of its ships in the Mediterranean and Red Sea. So did successive Egyptian viceroys.

So although the canal quickly became the most important of the Egyptian transit arrangements, its existence just confirmed what was already clear. Britain would stop any other power controlling Egypt, whenever the Ottoman empire tottered.

Power or trade?

In the late 1850s, then prime minister Lord Palmerston opposed the canal’s construction. This was not so much because he imagined that France could ever control it in opposition to Britain (though a few people did fear this). Instead he felt it could create a new source of tension between the European powers and raise again the questions about the integrity of the Ottoman empire that the defeat of Russia in the Crimean war seemed to have settled.

Many other British people did not worry about such things, and welcomed the canal as a symbol of peaceful global liberal modernisation. Likewise in France, Napoleon Bonaparte had, in 1800, urged an Egyptian canal as a way of challenging British rule in India. But most of its French proponents in later decades envisaged a civilising project uniting east and west and abolishing war.

Together with the completion of railroads and telegraph links across the United States and India, the opening of the Suez canal seemed a crucial part of the global communications revolution – something celebrated by Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in Eighty Days (1872).

International, but British

Britain supplied three-quarters of the canal’s shipping in 1870, and naturally became its major beneficiary. But as the historian Valeska Huber has shown in her book about the canal, despite the canal undoubtedly boosting the global free market, this process was neither trouble-free nor straightforward.

It helped the east African slave trade, and so created new pressures for its control. It also helped the spread of contagious diseases, prompting the establishment of a regulatory bureaucracy to monitor passengers, including on racial criteria.

Travellers noted the canal’s tedious bottlenecks, which meant that steamships were sometimes outstripped by dhows and camels, and were often vulnerable to canal works, strikes and accidents. By 1884, around 3,000 ships had been grounded along the route.

Moreover, British policy on the canal remained ambivalent. Approval of its contribution to international commerce could easily give way to panics that rivals like Russia might use it to attack India. In 1888, a major conference agreed to the internationalisation of the canal. All the European powers, the United States and the Ottoman empire stipulated that ships should enjoy free transit – not only in peacetime but also in war.

Britain, however, insisted on adding a rider reserving the right of the Egyptian government, which it now effectively controlled, to close the canal whenever order was imperilled. In the first world war, Britain closed the canal to enemy ships and restricted merchant use to daylight hours.

In this respect, the narrowness of the canal helped the controlling power to restrict access. Gladstone pointed out in 1877 that its dimensions made panic about a Russian assault on India via Suez ridiculous – ships could easily be scuttled there, or sappers employed to render it impassable in a few hours.

It is worth remembering, finally, the cause of the canal’s bottlenecks. It was built by a Franco-Egyptian private company with limited finances, which – until 1864 – was reliant on local forced labour. It was a ditch dug by conscripted Egyptians. Thousands died in its making.

The project allowed critics to portray Egypt as still a land of slavery. The biblical Israelites had escaped this slavery because of divine intervention, in the form of the parting of the Red Sea. The canal, the extension of the same sea, seemed – like the pyramids – to symbolise the oppression of the human spirit.

In that sense, the sight of the Ever Given wedged against this ditch has been another reminder of an obvious truth, that global capitalism rests on labour – the labour of those who toil now to make the factory goods that fill its stacked rows of massive containers. And the labour of those who earlier sweated to build this narrow link between those manufacturers and their markets.

Kenneth Clark at UEA in Civilisation (1969)

866 views•9 Mar 201670ShareSaveColm Gillis 27 subscribers Art historian Kenneth Clark visited the University of East Anglia, Norwich and presented part of the ground-breaking documentary Civilisation (1969) in front of the famous ziggurats.

Searching for Sir Francis Drake’s Golden Hind at Deptford, London Posted April 2nd 2021

Michael Turner and Susan Jackson,

supported by Sir David Nicholas, CBE

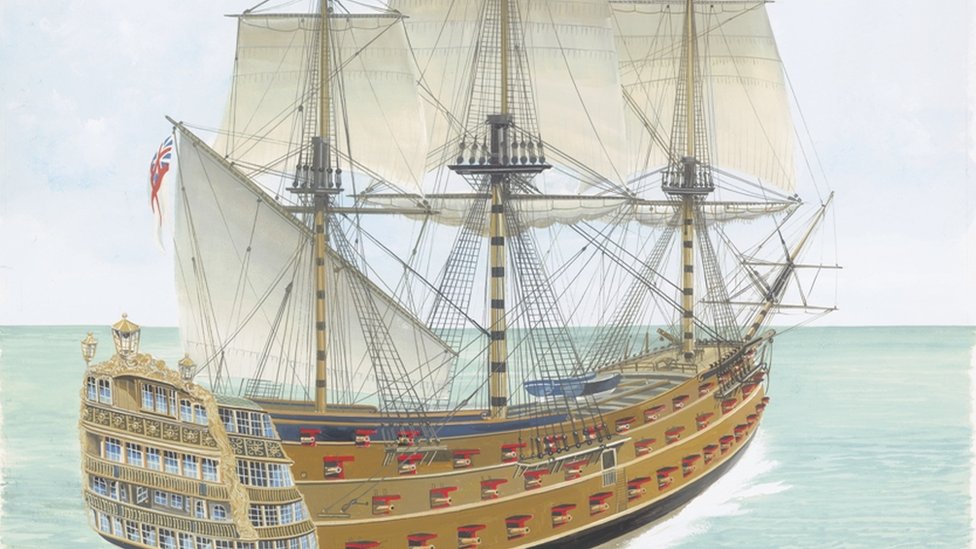

In 1998 Sir David Nicholas asked the late Ray Aker, president of the Drake Navigators Guild, California, if Ray could pinpoint the remains of Sir Francis Drake’s ship the Golden Hind. Between 1577 and 1580 this was the second ship to circumnavigate the world and the first to reach Cape Horn.

Deptford Strand

© Michael Turner 1997-2010

On 4 April 1581, probably at nearby Sayes Court, Deptford, Queen Elizabeth held the most extravagant banquet since the time of Henry VIII. She then boarded the Golden Hind, which was moored on the River Thames. She had Drake knighted on the main deck. The queen consecrated his ship as a memorial and according to John Stowe, in his Chronicles reprinted in 1592, ordered “His ship to be drawn up in a little crecke neare Deptford upon the Thames to be preserved for all posterity.” Another contemporary commentator William Camden in his Annales of England 1615, which he began writing in 1596, adds that the ship was “lodged in a docke.”.

Oppenheim, in A History of the Royal Navy wrote that the ship was placed in a dock and filled with earth. In the Navy accounts, only £35 8s 6d was expended for a wall of earth around her. In 1624 a new wharf was constructed by most likely building a new wooden wall on the outside of the original. Ray’s drawings convincingly depict the scene.

Golden Hind Dry Dock

The creek is the key to finding the ship, but it was filled in during the 19th century and its exact location has been forgotten. This creek was on the site of the Tudor Royal Navy Dockyard which in 1742 became the Royal Victualling Yard. Ray Aker has discovered its most probable location from a curious zigzag boundary line separating Deptford and Lewisham. The boundary line makes no sense in the modern layout of streets, parks and buildings; but it does if it is the bed of the ancient creek because rivers, streams and creeks are frequently used for boundaries. The creek was filled in because its water was diverted for the Surrey Canal.

On the basis of Ray’s new evidence, he expressed a wish that Sir David Nicholas, Michael Turner and Susan Jackson urge for an archaeological dig to recover the remains of the hull of one of the world’s most famous ships. Ray Aker wrote to Michael Turner asking him to examine the site of the old creek, featured on his map, where he was sure the remains of the Golden Hind lay. Here Ray identified old structures on the riverbank that may have originated from the dockyard days. In May 2009 Michael discovered that contrary to Ray’s expectation, there were no buildings over the site: only concrete and open ground. This was the best discovery for a straightforward excavation. The site lay inside Convoys Wharf, with old structures remaining on the riverbank. On the up-river side of the structures are river stairs that were more than likely built from the bed of the creek to save excavation. I had to scale a wall to obtain the photograph of the site through barbed wire. The indented stairs are on the left of the picture.

The site inside Convoys Wharf

Michael Turner 1997-2010

A very significant part of the ship is likely to have survived because it would not have been entirely broken up, because the remains starting from just below ground level would have been left to stabilize the infill once the decayed ruins were covered over in 1668.

On Monday 25 July 1988 the Daily Telegraph reported that a pile of granite stones which once formed a cairn to mark the spot where the ship lay had been found in a derelict garage. They were “tidied away” in 1977 after a visit from the Queen and afterwards forgotten, with only attempted demolition of the garage bringing them to light. It was said that they were being taken care of by a local archaeologist who was hoping to return them to their original place of honour. This did not happen, so where are the stones and where was the cairn? Old dockyard plans may also show the exact location of the cairn. Since a chair and a tabletop were made from some of the timbers, it seems most feasible that once the ship was filled in and buried, cairns would represent a tombstone for this legendary ship.

The Golden Hind at Deptford in an earth-filled dock

Raymond Aker

Susan Jackson argues that the two main reasons for searching for the Golden Hind are historical and aesthetic.