September 14th 2023

Andrea Bottner

From “borking” to getting “kavanaughed”: language, reputation, and the importance of a (male) name

M House – Feminist Media Studies, 2023 – Taylor & Francis

… Articles focused on Kavanaugh’s role as coach to his daughters’ basketball teams (Andrea

G. Bottner Citation2018; Darrah and Schallhorn Citation2018), and Kavanaugh himself …

SaveCiteRelated articlesAll 3 versions

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Andrea G. Bottner (born 1971 in Milwaukee) is an American lawyer, diplomat, Republican Party politician, political consultant and expert in women’s issues, especially violence against women. She served as the politically appointed Director of the International Women’s Issues Office of the United States Department of State in the George W. Bush administration from 2006 to 2009.[1]

Career

Bottner holds a BA degree in political science from the University of Delaware and a JD from the University of Baltimore School of Law. She was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 2000, and worked as an attorney representing battered women before serving as Deputy Chief of Staff to the Republican National Committee Co-Chairman Ann Wagner; Bottner was responsible for the national women’s outreach strategy during the 2004 George W. Bush presidential campaign.

She served in the George W. Bush administration as Principal Deputy Director in the Office on Violence Against Women of the United States Department of Justice, as Acting Director of that office in 2006[2] and finally as Director of the International Women’s Issues Office of the United States Department of State. As Director she established the U.S. Secretary of State’s International Women of Courage Award. After leaving the State Department, she founded Bottner Strategies, an advocacy firm.[3]

References

Andrea G. Bottner, United States Department of StateAndrea G. Bottner Appointed Acting Director of OVW, November 10, 2006

- Bottner, Andrea (12 March 2017). “After 30 years celebrating women’s history, have we made enough progress?”. The Hill.

- United States Department of Justice officials

- United States Department of State officials

- George W. Bush administration personnel

- 1971 births

- Lawyers from Milwaukee

- Living people

- American women’s rights activists

September 1st 2023

TikToker Mahek Bukhari and mum jailed for life for crash murders

By Dan Martin

BBC News

A social media influencer and her mother have been jailed for the “cold-blooded” murder of two men who died when their car was rammed off the road.

Mahek and Ansreen Bukhari recruited others before the killing of Saqib Hussain and Hashim Ijazuddin, both 21.

The fatal car chase in Leicestershire came after Mr Hussain threatened to reveal an affair he had been having with Ansreen, 46.

The court heard it was a plot of “love, obsession and extortion”.

Mahek – a 24-year-old social media influencer who the judge branded “entirely self-obsessed” – was jailed for life and ordered to serve at least 31 years and eight months.

Ansreen, whose head had been turned by the “perceived glamour” of her daughter’s career, was jailed for life and given a minimum term of 26 years and nine months.

https://emp.bbc.co.uk/emp/SMPj/2.50.4/iframe.htmlMedia caption,

Watch: What CCTV evidence showed us in the TikTok murder case

Leicester Crown Court heard the Bukharis “lured” Mr Hussain to a meeting in a Tesco car park, saying he would be given back £3,000 he claimed to have spent on his lover during their relationship.

They planned to take his mobile phone from him, believing it contained explicit images of Ansreen, which he had threatened to reveal.

However Mr Hussain and his friend Mr Ijazuddin were then ambushed by a masked gang, recruited by the Bukharis, and chased in their Skoda Fabia along the A46 at speeds of up to 90mph by a Seat Leon and Audi TT – before crashing into a tree in a ball of flames.

Judge Timothy Spencer KC said: “The prosecution categorised this as a story of love, obsession and extortion and they are right.

“They were also right in categorising this case as one of cold-blooded murder.”

The judge said TikTok and Instagram, where Mahek Bukhari had amassed tens of thousands of followers posting beauty and fashion advice, were at the heart of the case.

He told Mahek: “Your tawdry fame through your career as an influencer has made you entirely self-obsessed.”

He said her “warped values” had led to her having “no apparent awareness” of the impact her actions had on others.

She blew a kiss to her father, present in court, as she was taken from the dock to start her jail sentence.

- TikTok murder families speak of ‘devastation’

- Murder-accused TikToker ‘told a pack of lies’

- TikToker and mum ‘killed men in plot to hide affair’

The judge said Ansreen’s head had been turned by the “perceived glamour” of her daughter’s career, with her often appearing in posts online and attending promotions and shisha bar openings.

He said it was a world removed from her life as a mother and housewife.

He told her: “You are the grown-up in this group and you should have behaved as the grown-up but you allowed your understandable concern about exposure to strip you of any rational judgement.”

He said she had made a “calamitous decision” to ask for Mahek’s help with Mr Hussain.

He cited two key WhatsApp messages from Mahek.

One said: “I’ll soon get him jumped by guys and he won’t know what day it is… I’ll make sure he gets jumped, he won’t know who did it and how.”

Earlier on Friday, the court heard statements from the families of the victims, in which the parents of Mr Hussain and Mr Ijazuddin said their lives had been changed forever.

Mr Ijazuddin’s father, Sikandar Hayat, said his son, who accompanied his friend to the rendezvous that ultimately led to their deaths, had been “innocent”.

He said he could not understand why the defendants had not called the emergency services after the crash.

“They left him and his friend to burn in a furnace of hell,” he said.

In a statement read on their behalf, Mr Hussain’s family said his parents had been left as “two lifeless corpses”, unable to eat or drink in the run-up to their son’s funeral.

‘Moving and distressing’ evidence

During the trial, a 999 call made by Mr Hussain in the moments before the fatal crash was played.

He told police call handlers: “There’s guys following me, they have balaclavas on… they’re trying to ram me off the road.”

A scream was heard on the line before the call abruptly ended.

The judge said: “It was one of the most moving and distressing pieces of evidence ever heard in a criminal court.”

Also sentenced for murder were fellow defendants Rekan Karwan, 29, and Raees Jamal, 23, who were recruited by the Bukharis and driving the pursuing cars.

The court heard Jamal is serving a sentence for rape.

In the courtroom

George Torr, BBC News

The heartbreaking saga for the Hussain and Ijazzudin families is finally coming to an end.

It’s difficult to put into words just how painful it has been for them since their sons’ deaths back in February 2022.

Mr Hussain’s father Sajad and Mr Ijazzudin’s father Sikander have spent every minute inside this courtroom in Leicester, making the journey every day from their Oxfordshire home to the East Midlands.

Mahek Bukhari, the ringleader, is now a shell of her former self the press have observed.

She shared smiles and laughs with other defendants during quieter parts of the trial, and casually played board games in the precinct when the jury retired.

She casually played Monopoly and the card game Uno while she waited for the jury to come back with a verdict.

She even waved and laughed at reporters outside with cameras from a balcony in the court foyer just hours before she broke down in tears when she was convicted of double murder.

The judge said Mahek approached Karwan as “a go-between”, before Karwan “brought in Raees Jamal”.

He said it was not chance that Karwan took over the driving of the Audi when the fatal pursuit took place.

He suggested Raees Jamal was enthralled with Mahek, despite being in a relationship “of sorts” with fellow defendant Natasha Akhtar, and was willing to “do her bidding”.

The judge said Ameer Jamal and Sanaf Gulamustafa were “willing recruits” in the ambush.

He added lies told by Akhtar revealed she was an “integral part of this venture” and she was either “deluded” or found lying second-nature.

The defendants

- Mahek Bukhari, of George Eardley Close, Stoke-on-Trent, was jailed for life with a minimum least 31 years and eight months in prison

- Ansreen Bukhari, of George Eardley Close, Stoke-on-Trent, was jailed for life with a minimum term of 26 years and nine months

- Rekan Karwan, of Tomlin Road, Leicester, was jailed for life with a minimum of 26 years and 10 months

- Raees Jamal, of Lingdale Close, Loughborough, was jailed for life with a minimum term of 36 years and 45 days. He must serve five years on top of the 31 years he was given on Friday – the unexpired portion of his rape sentence

- Natasha Akhtar, 23, of Alum Rock Road, Birmingham, was sentenced to 11 years and eight months for manslaughter

- Ameer Jamal, 28, of Catherine Street, Leicester, was jailed for 14 years and eight months for manslaughter

- Sanaf Gulamustafa, 23, of Littlemore Close, Leicester, was sentenced to 14 years and nine months in prison for manslaughter

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, on Twitter, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk.

August 26th 2023

I Deeply Love My Kid, I Just Can’t Stand Playing With Him

My son is gentle and loving. I am proud of him. But playdates, parks, and pretend—they still make me want to do almost anything else.

More from Vogue

- How the World Fell Head Over Heels for RuPaul

- Royal Sibling Relationships Have Always Been Complicated

- The 20 Best Memes of 2022

Advertisement

The author with her son, Guy. Photo: courtesy of the author.

I want to suck in my son Guy’s morning breath so that his particles live in my body where I can keep them safe. I want to rip off his socks and lick the saltiness of his fat toddler feet. Though it seems to change every hour, I want to memorize his face. I cherish everything about him. But I’d rather do anything else than have to play with him.

When I was seven months pregnant—inwardly spiraling about the fact that I had no real vision for myself as a mother, that I hated my new body, that I’d been depressed basically since my mid-20s—my partner and I met friends for dinner, two husbands who had just had their first child by surrogate. They brought the little boy with them, asleep in a bassinet at our feet while we ordered a quick meal. They looked miserable and exhausted.

Don’t worry, they said when we asked gingerly how things were going. It won’t be this hard for you. You’ll have maternal instincts to rely on. Men don’t have those! Everyone laughed, but I wasn’t sure what the fuck maternal instincts I was expected to have, or when they’d kick in. I didn’t even really feel like I wanted them, in fact. Having them might change me, and I was already changed enough, already spending so much energy on the correct way to become a good mom: Choosing the right brands so I could buy the right stuff, repeating the right platitudes about the impending birth to seem the right amount of happy and grateful. Though there is no known scientific evidence for mom brain, it is across the board acknowledged by birthing persons as a symptom that is generally suffered. I wasn’t sure if that’s what I should call my mental status, but seven months in, and I knew that my instincts had yet to miraculously start.

Guy wasn’t cute when he was born—which didn’t help my feelings about him, and my embarrassment that I didn’t immediately love him and find him perfect. His head looked like it had been through a fro-yo machine the first time I saw him, and his eyes crossed and dilated in anything but semi-darkness. He was so scrawny, with translucent skin and blue veins stretched over his amphibian bones, fresh out of amniotic water. Most women I talked to in those months said things like don’t you wish you could bottle the smell of his head? Shamefully, his baby smell never did it for me, and the idea that I would find joy in something as ephemeral as his scent seemed like I was tempting the fates to take him.

I worried endlessly about his death, after all, manifesting in multiple nightmares a night which kept me awake for more hours than anyone should be awake. Here we are again, I thought, every exhausted morning when I came up with new ways to not play with my child. I’d stand in front of my son’s closet, folding and refolding onesies and socks, making lists of things he “needed”; trying to find solace in something I was good at—consumerism—which never seemed to work. Or, I’d leave him here and there in the care of other women, whose help I was so lucky to be able to pay for—a privilege utterly unavailable to most mothers raising their children without community, without government and legislative support—and off I’d go, claiming a dermatologist appointment or workout class, mixed with acupuncture for my PTSD and two kinds of therapy, believing in the late capitalist sophistry that enough self care would make me happy.

Within a year, Guy’s hair darkened and grew into soft brown baby curls, his big, tweety-bird eyes solidified in their sockets, and his full pout gave him the look of a tiny rock n roll star, pursing for a long-legged Bambi love interest. He started talking, and almost immediately became a little jokester. He’s gentle and loving. I am proud of him. Proud of his kindness and curiosity. However I have to admit: music class at the local library, playdates, playgrounds, parks, and pretend still make me want to do almost anything else, still make my brain feel numb and bored and uninspired, desperate to focus on something more adult.

When the World Trade Towers fell on September 11, 2001, I had never heard of them. I’d never been to New York; I only knew the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty, which has a poem at the base that I had to memorize for history class when I was in eighth grade in Indiana, just a couple years before. The world was different then, I guess. The internet was nascent. I wasn’t allowed to watch Sex and the City, or even Felicity; all I knew of New York was from the Bell Jar and a Tree Grows in Brooklyn, or the stories my maternal grandparents told me about their American dream childhoods.

Twenty years later, when I was established in my career as an art dealer, I took a call from a friend who was a curatorial representative at the Oculus, Calatrava’s monolithic, spine-shaped, surreal hub which replaced some of the fallen buildings at Ground Zero. She was trying to fill an 800,000 square foot atrium—a stark white, soaring hall roofed by what look like architectural ribs—with art that could be engaging and impactful to the public. I immediately thought that whatever was in the rotunda could function as a respite for the heaviness visitors would be confronted with right outside. I started searching for something big and optimistic for her.

Nancy Rubins, an American sculptor who makes large-scale works by transforming heaps of industrially made items—like mattresses or single-person airplanes—into impressive sculptures came to mind. In one series, Rubins took aluminum animal-shapes, reclaimed from playgrounds, and welded them together in rhizomatic structures secured by ropes. They reminded me of the idea espoused by the early 20th century Dutch theorist Huizinga, in his seminal text Homo Ludens, that humans are driven by an innate desire for fun; that playing teaches biologically important skills and lessons, is a necessity fulfilled in different ways at different ages.

I sent my curator friend these works, sure she’d admire their spirit of buoyancy and cheerfulness, and she called me almost immediately. Thank you for sending your proposal, she said, leaking calm tears as she explained that they couldn’t proceed with it. World Trade Center 5 had a nursery, she explained. The kids were all rescued, but it was such a traumatic moment—I don’t think these sculptures would be right. I cried, too, when she told me. Of course I was horribly sad for those babies and their families—those tiny children just learning all the ways that life would allow them to play—living through an act of immense violence; an act completely at odds with joy and humanity. But it also made me think of the capacity for resilience and optimism that children have, and how they can feel protected and nurtured in so many ways.

Tremendous research has been done regarding the connections between mothers and children and the types of interactions that lead to kids becoming successful adults. The psychologist Beatrice Beebe has written extensively about the importance of simple recognition. From 10 minutes after birth, babies interact with adults, communicating through a series of small movements that mimic and react to behaviors they see around them. Beebe has been able to track patterns of interaction occurring as early as four months and favorably correlate them to future intelligence and social development. Her work has been used to support legislation at the state level to encourage more generous parental leave, as well as education for OBGYNs providing care to Medicaid patients.

I do not doubt that my lack of interest in play is related to the type of attachment I had to my own mother—who wasn’t so into play herself—which I would guess could be in turn related to how she interacted with my grandmother, and so on. I also do not doubt that a factor in my feelings on play was my own mental state after Guy was born. For traumatized mothers—ones who had less than perfect childhoods themselves, or maybe those who suffer from any sort of postpartum depression and disappointment with the narratives surrounding motherhood, like me—connecting to and recognizing the emotional states of babies can feel like more of a challenge.

When you have a child, by any means, you owe it to that baby to do your best to love it and teach it to be loving, but perpetuating unattainable and unnecessary norms of what motherhood “should” look like—when research shows us that interaction, not specific to play, is what’s essential—feels like just another way to judge women and birthing persons. Instead, we need to be facilitating conversations about all the ways being a mom can look; that there are wonderful parents for whom playing is second nature, and others, like me, for whom it’s not. In a world that is more authentic and honest about the various realities of motherhood, we will inevitably be rewarded with more support for those diverging realities, a greater sense of community among parents, and a more broad and diverse narrative about what parenthood can be, which is essential to creating a world that is more just and equitable for all types of mothers everywhere.

I’ve made peace with the seeming contradictions in my love for Guy—that instead of going to the park, I prefer to take him for my matcha and a baked good outside of traditional meal times; or that I bring him as I run my own errands, asking him questions about school and life. It’s okay that I’ve found the types of play that I can tolerate, like coloring, and enjoy those with him in short increments, usually less than 15 minutes. It’s okay that when he asks me to engage in other types of play, I make a clear boundary. Mommy doesn’t have fun doing that, but I will be right here reading while you do it! And then we can talk about it. Everybody likes different things. His daily, effusive joy and happiness is proof that he knows he is cared for, that he feels connected to me, that he knows we can lovingly interact, even if not via games of pretend.

Guy and I have our own world where we are enveloped in a bubble of our love, as different as it may appear when compared to other peoples’ bubbles. When I walk down the street holding his small, warm hand, listening to him point out the new words he’s learned like double-decker bus or maple tree in his sweet little stammering voice; when he asks me to stop at every deli to smell the dyed flowers outside in their plastic buckets and proclaim that each of them is yummy!; when he puts new sneakers on his pudgy, clumsy feet and walks like he put on new legs, I’m so filled with pride and love and a connection that exists with no one else.

Sarah Hoover

August 16th 2023

When it comes to experts on TV, women are still neither seen nor heard

What does an “expert” look like? If you took the example of news media, it would invariably be a man; usually – in Britain anyway – a white, middle-aged man.

Women make up roughly half of the world’s population and have also increased their representation in public life over the past ten years. And yet when journalists reporting for television, radio or newspapers turn to an expert, it tends to be male. But while you may have started to notice that every panel on TV has three men to every woman, you might not realise just quite how extensive this imbalance is.

Since 1995, the Global Media Monitoring Project has carried out research into gender and the media. Every five years, volunteers around the world record a snapshot of the gender representations in news stories over one day. The methodology of the survey has been updated and improved with each survey – and 114 countries participated in the last one. Sadly, the results have changed comparatively little. According to the Who Makes the News report, compiled from the findings in 2015, in newspaper, television and radio news women accounted for just 24% of the people heard, read about or seen. That figure hasn’t changed since 2010. In addition, only 10% of all stories focused on women, a figure unchanged since 2000.

You might assume those numbers are skewed by countries where women play less of a role in society. However Lis Howells of City University in London has analysed the numbers of female contributors on the UK’s flagship broadcast news programmes – including ITV News at Ten, Channel Four News and the Today programme on BBC radio 4. Her research has shown that male contributors still outnumber women by three to one – and that’s an improvement from six to one in 2011 thanks in part to a campaign by Broadcast Magazine.

Disinformation is dangerous. We fight it with facts and expertise

But there is an additional problem. When women do appear in broadcast news, according to journalism academics Karen Ross, Karen Boyle, Cynthia Carter and Debbie Ging, they invariably fall into several stereotypical categories. Increasingly they tend to be interviewed about their personal experience – often as victims of crime, or as parents or as consumers. They also appear far more often than men in health stories. Where they tend to appear far less is as authoritative or elite sources in political or economic stories.

The Fawcett Society highlights that the press also tends to mention what women are wearing. This is also true of the coverage of sportswomen. Meanwhile, the images of women we are given in many newspapers are generally sexualised and stereotyped. It’s an issue the campaign group Object highlighted to the Leveson Inquiry into press standards. Anna Van Heeswijk, the CEO of Object, told the inquiry that in many cases there was “no marked difference” between pornography and some of the pictures in the UK tabloids.

As a political journalist for the BBC Northern Ireland programme Hearts and Minds for around a decade, I spent a lot of time trying to find female contributors – but if women simply didn’t want to take part, it then seemed acceptable to fall back on the male experts who were generally available and spoke well. As a listener to the media I used to produce, a lot of the time I still hear the same men on air that I was interviewing five years ago.

Everyday sexism

It’s easy to understand why women can be reluctant to be interviewed for broadcast. When a woman gives her opinion in public there’s always the chance she is opening herself up to abuse. The renowned professor of classics, Mary Beard, suffered intense online trolling after appearing on television. And when the Guardian analysed 70m online comments on its articles, it found that of the ten people who received the most abuse, eight were women.

In addition to that, women tend to find it harder than men to ignore “imposter syndrome” – where they feel as if they are not qualified to talk about a given subject, even if they are experts. And while there have been campaigns by broadcasters to offer media training to women, unless these potential new contributors are flagged up to journalists, they are unlikely to be used.

The issue of women in news and current affairs broadcasting was the subject of an inquiry by the House of Lords Communications Committee in 2015. Its report called on public service broadcasters “to reflect society by setting the standard in ensuring gender balance”. Similarly, the National Union of Journalists highlighted the low numbers of female senior managers in news organisations – and the Lords committee report backed the union’s recommendation that this be addressed through positive action in recruitment and promotions.

Token efforts

In 2014, Danny Cohen, then the BBC’s director of television, told The Observer that the BBC would no longer broadcast all-male panel shows. This seems like a step forward, but there is a danger of that smacking of tokenism – as Buzzfeed has shown.

Despite refusing to join Broadcast Magazine’s campaign (the BBC explained as a public broadcaster its “primary role is to ensure the people who appear on our programmes are qualified to tackle the issues we explore”), the corporation launched an “Expert Women” training course in 2014.

A number of organisations have begun to compile their own lists of female experts – in an attempt to counter the argument that women speakers are not out there. In the Republic of Ireland the group Women On Air has increased the number of women appearing on the national broadcaster RTE through their creation of The List. The Women’s Room – which campaigns on the issue – has a database of female experts.

But this is not a problem that women should have to solve. Many are now challenging and mocking gender inequality when they see it. The Twitter account Academic Manel Watch (@manelwatchire) was set up to object to the use of all-male panels in Irish academia. It follows on from the successful AllMalePanels blog with its distinctive “Hoffsome” stamp. And that’s a badge of honour that no organisation should want to be awarded.

Fake news, disinformation, conspiracy theories …

If you are struggling to know who or what to trust, it’s little wonder. The consequences are real: democracy is threatened and, in some extreme cases, civil unrest and even armed conflict erupt. Now, more than ever, people need to be able to turn to reliable, evidence-based and non-partisan journalism. I help curate our daily email and this is what it offers: trusted news written by academics and experts.

Jonathan Este

Associate Editor, International Affairs Editor

When we give AI a humanoid form, we typically choose the robot to have feminine characteristics. Are we playing on stereotypes?

By Mark Shea7th August 2023

When we give AI a humanoid form, we typically choose the robot to have feminine characteristics. Are we playing on stereotypes?

There is a popular idea that artificial intelligence (AI) is out to get us.

It was this public image problem that the United Nations was recently trying to address at its AI for Good conference in Geneva.

The event in July was intended promote AI to help solve global problems, and it was described as the largest-ever gathering of humanoid robots.

There was Ai-Da (the “world’s first ultra-realistic humanoid robot artist”) and Grace (the “world’s foremost nursing assistant robot”) as well as Sophia, Nadine, and Mika. There was even a rock star robot, Desdemona.

All of these androids have one thing in common – they are all female by design. So why is it that creators typically choose to give their robots feminine characteristics?

It is often argued that the choice to make AI voice systems female is rooted in gender bias. But sometimes there is a more innocent reason for the sex a designer gives their robot: they have modelled it on themselves.

You might also like:

- The truth about sex robots

- The AI emotions dreamed up by ChatGPT

- The Martian robots that came to life

This is the case with Nadine, whose creator Nadia Magnenat Thalmann describes her as a “robot selfie”. Meanwhile, Geminoid, the only robot at the conference that was explicitly male, is the spitting image of its maker, Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro.

One of the keynote speakers at the conference was Ai-Da, an AI machine which can draw, paint and sculpt, and is also a performance artist.

Lisa Zevi, head of operations for the Ai-Da project, tells the BBC that in this particular case, there was a good reason for giving Ai-Da a broadly female look.

“Female voices are typically very underrepresented in both the art and technology spaces,” she says. “We want to give a voice to those underrepresented groups effectively.”

Specifically, Ai-Da’s persona is inspired by Victorian mathematician Ada Lovelace – considered by many to be the first computer programmer – as is her appearance.

Other than those robots modelled on an individual, one particular reason is often suggested for choosing a female robot: we have an innate preference for women’s voices.

Karl MacDorman, an expert in robotics and human-computer interaction from the University of Indiana in the US, believes this argument may have a basis. He has conducted research which has found that women prefer women’s voices, and men do not really have a preference.

Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro is one of the few designers to make a human-like robot with male features (Credit: Getty Images)

By testing their reactions to voices, the research found a discrepancy between what people report on questionnaires and what they really feel – women like a female voice far more than they admit, and men say they greatly prefer a female voice on questionnaires (even though they don’t really care).

“Thus, a female voice may work better for both groups. Women on average are happier interacting with female voices, and men believe they should be happier, even if they’re indifferent,” MacDorman concludes.

This might not tell the whole story though.

Early versions of AI like Siri and Alexa were given female voices, and MacDorman’s work has been quoted as justification for this choice. Yet he believes some major corporate decisions had already been made for entirely different reasons, and his findings were simply convenient.

Women like a female voice far more than they admit, and men say they greatly prefer a female voice on questionnaires

“I suspect they had made their decision before I had published any work on this topic,” he says. “They probably made the decision for reasons that are unconscious, or reasons that they might not like to admit to, and then they need the justification for it later when they are challenged.”

MacDorman believes our own expectations may play a bigger part in the decision-making than many designers are prepared to admit. “In terms of quality of service or customer service roles I think that they may be more associated with women than with men.

“The initial stereotype then becomes reinforced just because it becomes a popular choice to give artificial intelligence a female voice.”

MacDorman believes that this could be considered sexist, because the roles that AI typically performs – delivering information or customer service – are in a sense servile.

And he hints that this may also play into male fantasies.

Kathleen Richardson, professor of ethics and culture of robots and AI at the UK’s De Montfort University, remembers when humanoid robots did not typically take an adult female form.

“In the lab that I was in [15 years ago], they always made them child-like,” she tells the BBC. “The idea was, if they were childlike, they wouldn’t be threatening to people, and people would be more comfortable with inviting them into their home.”

Ai-Da has been described as the “world’s first ultra-realistic humanoid robot artist” (Credit: Getty Images)

Richardson says this drive to make androids less threatening has morphed into the female forms that we see today, and it is driven by the preoccupation that we have about the increasing role that technology is playing.

“You’ve got to dislodge this very deep fear of depersonalisation and dehumanisation that comes with introducing more technologies into our lives, particularly in our personal arenas,” she says.

“People write reams of how terrifying it is, how the terminators are around the corner. That would be terrifying to have in the home, right?”

MacDorman – who has also worked with robots for decades – agrees these fears had a role in robot design, especially early on. “A female android is generally considered more approachable, especially for children, so it was considered better suited to human-robot interaction experiments,” he says.

We can’t just transfer what’s going on inside people and inside people’s relationships to these new artefacts – Kathleen Richardson

This tallies with his experience of working on robots in Japan between 2003 and 2005 – many of the experiments were with children and the team he worked with believed a female android seemed less threatening.

But Richardson suspects that there may be an altogether more basic motive at play in modern designs of humanoid robots.

She likens robots to art – what you see is just an image on a surface – and believes that robot design suffers from the same issues that modern art critics often lament when they appraise historical paintings.

“There was a famous theorist called Laura Mulvey who talked about the male gaze in art, and how male artists were representing female figures. They were normally representing them as submissive, as naked, as objects of male desire. And I think in a way, we’re seeing the male gaze just replicated in robotics, because these are just images on surfaces – there’s nothing that that sits behind these images. There’s no sentient being. There’s no life.

“We can’t just transfer what’s going on inside people and inside people’s relationships to these new artefacts that are created.”

The sci-fi film Blade Runner is one movie which explored the idea of artifical humans created for sexual purposes (Credit: Warner Bros/Getty Images)

When she looks at the anthropomorphic adult female figures on display at the Geneva conference, Richardson says she sees “a bunch of puppets”.

MacDorman agrees that heterosexual male designers – and it is a very male-dominated industry, he says – are choosing to make their creations female because of their interest in the opposite sex.

“There’s definitely a sexualisation. The more realistic the robot and the more realistic the voice, the greater the tendency to sexualise it. If it’s something very realistic, there’s the tendency to see it or to treat it as if it were human. It’s kind of pressing our Darwinian buttons, so to speak,” he says.

Where could this sexulisation of robots end up? Richardson fears a future in which robots are routinely used for sexual purposes. Her Campaign Against Porn Robots aims to draw attention to the ethical harm of normalising such uses of this technology.

The idea of having sex with an android has existed in mainstream entertainment for decades, in science fictions films such as Blade Runner, AI Artificial Intelligence, Her and Ex Machina.

In her book Man-Made Women, Richardson warns of a growing trend – the idea has jumped from science fiction to morning talk shows and music videos. Sex doll brothels are opening in Barcelona, Berlin and Moscow.

There’s a concern generally with AI, especially when it’s related to sex: human relationships are difficult – Karl MacDorman

“For those wanting to attend talks on the subject there is even an annual international conference on love and sex with robots,” she writes.

She cautions that there would be a massive cost to normalising such interaction. “What we’re building into society is this very egocentric idea that actually what a single human being is feeling and thinking and experiencing is “a relationship”. So they can project onto an AI avatar all these feelings.

“But people know intuitively, a relationship involves two parties. It’s not just something happening in one person – it has to be something that happens between you and another person. And the relationship is the bit in the middle, really, isn’t it? It’s not going on just on one side or the other.”

MacDorman sees the potential for a growing industry to evolve around this function.

“There’s a concern generally with AI, especially when it’s related to sex: human relationships are difficult. There’s risk involved with any kind of intimacy, and AI is more compliant.”

Some people find pornography easier than dating, he says, and AI could provide a way of avoiding the effort of dealing with other human beings, and the fear of rejection that this brings.

Many recent AI assistants have also taken on a female form – a trend that has become hard to reverse (Credit: Getty Images)

One particular danger, he says, is that the often servile nature of AI can feed people’s narcissism.

But the high price of such robots may act as a limit to their adoption. “In order to build an android, there’s considerable cost relative to other kinds of robots,” he says. “To make them realistic is expensive.”

He sees more of a future in animated characters which are interactive, rather than three-dimensional humanoid “companion bots”. “Pretty much anything with moving parts is going to be problematic. Think about the attention the automobile requires compared to whatever computer you’re working on.

“You probably use the computer for a much longer period of time throughout the day, and it requires much, much less attention.”

He thinks that regardless of our erotic desires, humanoid robots will therefore remain unaffordable for most consumers.

Most – but not all. “Just as some people can afford supercars, there will be those who can afford androids,” he says.

July25th 2023

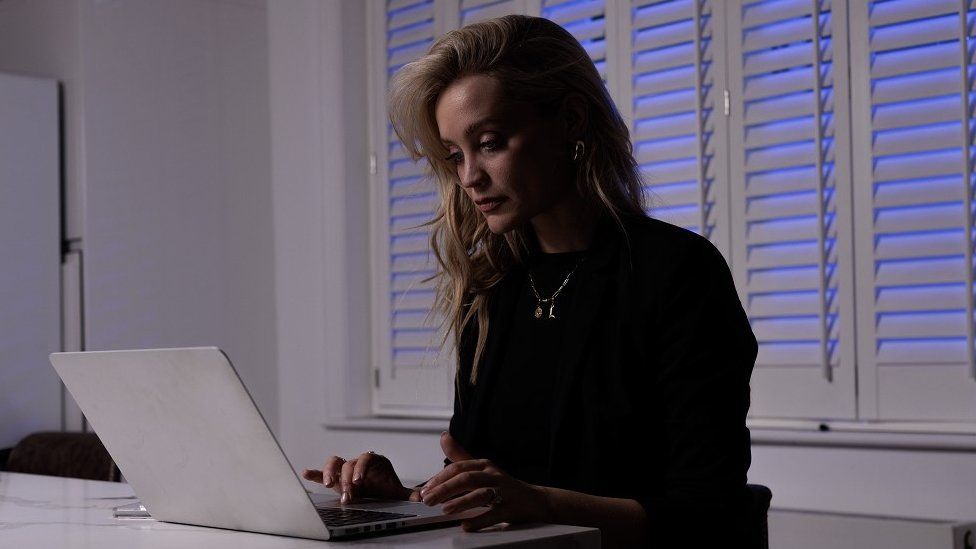

Laura Whitmore on incels, rough sex and cyber stalking

- Published

- 12 hours ago

By Helen Bushby

Entertainment reporter

Broadcaster Laura Whitmore is arguably most famous for appearing on shows with a “fluffy façade”, such as Love Island and Celebrity Juice, but her upcoming TV series could not be more different.

It started as a documentary idea about incels – young men describing themselves as “involuntarily celibate”, who hold misogynistic beliefs, with some launching violent attacks.

But this soon morphed into two more episodes on rough sex and cyber stalking.

“Although I’ve worked on things that might have a fluffy façade, I’ve always dealt with dark situations – we all do in life,” she tells the BBC.

Her goal was for the series to explore topics that are “really important, and that I feel are worth it”.

The result was ITV’s Laura Whitmore Investigates. We see her flex her editorial muscles, having done a journalism degree at the start of her career.

ITV’s controller of factual programmes, Jo Clinton Davis, has said the issues in the series “feel like peculiarly 21st Century threats emerging from, or aggravated by, our online world”.

Whitmore is hoping to offer a fresh perspective, saying: “I think it hasn’t really been looked at this way, from a female who is known probably from a more entertainment, glitzy side.”

It is quite a juxtaposition with her recent work on ITV, as former host of reality dating show Love Island, and team captain on comedy panel series Celebrity Juice.

She has tackled serious issues before, however, joining campaigners in 2018 calling for the criminalisation of upskirting, the taking of an image or video under somebody’s clothing.

Whitmore was not afraid to tackle the complex, often troubling documentary subject matter, even if it meant putting herself into uncomfortable situations.

“I came into this to try, as much as I could, to be without prejudice – a blank canvas – because they’re not necessarily my stories,” she says.

“I’m a female in her 30s who has definitely dealt with misogyny – but not to the extremes that a lot of women and men who I talk to.

“One thing I’ve learned over my career is that you need to question things you’re not okay with and don’t understand. And you can completely change your mind.”

In the cyber stalking episode, Whitmore reveals that she herself has been stalked.

She tells the BBC: “I had an incident, and at the time, I was told, ‘It’s just part of the world you live in; that’s the job you do,’ and it was common to have to deal with it.”

Whitmore meets cyber-stalking victims and spends time with the UK’s first special stalking police unit, learning what can be done to properly tackle the problem.

She also speaks to a tech company helping victims by “stalking the stalkers” to reveal their identity.

“We are a lot more vulnerable than we know,” she says.

“People have access to us in a way I couldn’t possibly understand beforehand.

“It’s not just stalking someone hiding in the bushes outside your house, this is ex-partners still having control over the Alexa in the house and the heating, and ordering pizza in the middle of the night.

“If you add all these together, it is harassment. And I can see what it’s done to victims. A lot of them don’t want to leave their house now.”

Whitmore does not shy away from exposing her own vulnerabilities in the series, something which was also very apparent the day after her friend Caroline Flack took her own life in 2020.

Fighting back tears on her Radio 5 Live show, she paid tribute to the “vivacious” and “loving” ex-Love Island host and appealed to listeners to “be kind” to others.

Whitmore reflects back on this incredibly difficult moment.

“I think I did it because I needed to do if I’m honest with you, at that time. I said what I needed to say. But I still don’t think I’ve fully dealt with that if I’m honest.”

Whitmore also reveals she had an unexpected response after interviewing an incel in the US with a big social media following, for the documentary series.

She admits she had been “nervous”, given he was so openly hostile to women.

“I’m leaving myself vulnerable. So I’m not gonna lie. I was a little bit hesitant,” she says. “But you don’t get anywhere in life burying your head in the sand.

The interviewee did not show his face to her.

“I was really surprised… he was wearing a mask – that could be quite a intimidating situation.

“And then l left feeling sorry for the man I’ve interviewed. That wasn’t expected.

“This was a man who from a young age needed help and never got it.”

She stresses that while she does not in any way condone his views and videos, she did gain much more understanding, having heard him talk about his early life.

“And I think when we understand the why, we’re like, ‘Well, how do we stop that? Is there a way we can reach out and help them?'”

‘A bit embarrassed’

Whitmore feels that we “we don’t deal with or talk about” difficult issues enough”, which is why she’s keen to raise difficult issues in her series.

“I know I’ve been in situations before where it’s easier to say nothing than be uncomfortable. But I think it’s important to be uncomfortable,” she adds.

The rough sex episode is a case in point.

Whitmore is exploring its “dark side”, and asks whether “increasingly liberal attitudes to sex promote sexual violence”.

We see her attend a BDSM workshop and a pornographic film shoot.

“I grew up in Catholic Ireland and went to a convent school, and you didn’t really talk about sex, and were kind of a bit embarrassed,” she says.

“There’s so much more conversation around the importance of consent than I thought, when it comes to talking about what we are okay with – and not okay with.”

In the same episode, we see her meet the families and victims of rough sex.

Whitmore asks if BDSM culture has “given men the excuse they need to get away with murder”, highlighting the women killed by men who have gone on to claim in court it was a “sex game gone wrong”.

This episode had the biggest impact on her personally.

“I think that’s because I spoke to so many victims’ families,” she says.

“I started my career in a newsroom, and always thought I wasn’t built for it because I was probably too emotional as a person. I found it really hard to step away. And I still do now.”

‘I feel really protective’

We see her crying on camera when she speaks to the relatives.

“I think with documentary making, it’s okay to have a bit of emotion in there,” she explains. “But I found that really hard.”

As associate producer, she was also able to tell the families and women she spoke to about the documentary as a whole.

“I said to them,’Look, I’m going to BDSM workshops at the start but that’s nothing to do with this part of it.’ So I felt at least I have a chance to look at the edit and go, ‘Can we move this around?’

“I feel really protective over how we display those interviews, and how they’re done.”

Whitmore, whose career also includes hosting podcasts and starring in West End supernatural thriller 2:22, says making the documentaries was also about “claiming my power… and personal autonomy”.

“I’m in my 30s now, so it’s very different from when I started out on MTV in my early 20s.”

But she doesn’t think she could do documentaries full-time.

“I still love entertainment. I think I need both,” she says.

“I just enjoy people. I enjoy storytelling. I find that fascinating.”

Laura Whitmore Investigates is available to stream on ITVX from 27 July

Related Topics

- Laura Whitmore steps down as Love Island host

- Published22 August 2022

- Incels: A new terror threat to the UK?

- Published13 August 2021

- Inside the dark world of ‘incels’

- Published13 August 2021

June 18th 2023

How did patriarchy actually begin?

By Angela Saini30th May 2023

For centuries, people have held mistaken assumptions about the origins of male-dominated societies, writes Angela Saini.

I

In 1930, when London Zoo announced its baboon enclosure would be closing down, the story made headlines.

For years, “Monkey Hill”, as it was known, had been the scene of bloody violence and frequent fatalities. The US news magazine Time reported on the incident that proved to be the final straw: “George, a young member of the baboon colony, had stolen a female belonging to the ‘king,’ the oldest, largest baboon of Monkey Hill.” After a tense siege, George ended up killing her.

Monkey Hill cast a long shadow over how animal experts imagined male domination. Its murderous primates reinforced a popular myth at the time that humans were a naturally patriarchal species. For zoo visitors, it felt as though they might be peering into our evolutionary past, one in which naturally violent males had always victimised weaker females.

In truth, Monkey Hill wasn’t normal. Its warped social environment was the product of too many male monkeys being placed with tragically too few females. Only decades later – with the discovery that one of our closest genetic primate relatives, bonobo apes, are matriarchal (despite the males of the species being bigger) – have biologists accepted that patriarchy in our own species probably can’t be explained by nature alone.

What was happening at Monkey Hill in London Zoo was not typical (Credit: Getty Images)

Over the past few years, I’ve been travelling the world to understand the origins of human patriarchy for my book The Patriarchs. I learned that, while there are many myths and misconceptions about how men came to have as much power as they do, the true history also offers insights into how we might finally achieve gender equality.

For starters, human ways of organising ourselves actually don’t have many parallels in the animal kingdom. The word “patriarchy”, meaning “rule of the father”, reflects how male power has long been believed to start in the family with men as heads of their households, passing power from fathers to sons. But across the primate world, this is vanishingly rare. As anthropologist Melissa Emery Thompson at the University of New Mexico has observed, inter-generational family relationships in primates are consistently organised through mothers, not fathers.

Among humans, patriarchy isn’t universal either. Anthropologists have identified at least 160 existing matrilineal societies across the Americas, Africa, and Asia, in which people are seen to belong to their mothers’ families over generations, with inheritance passing from mother to daughter. In some of these communities, goddesses are worshipped and people will stay in their maternal homes throughout their lives. Mosuo men in southwestern China, for instance, might help raise their sisters’ children rather than their own.

Often in matrilineal communities, power and influence are shared between women and men. In matrilineal Asante communities in Ghana, leadership is divided between the queen mother and a male chief, who she helps to select. In 1900, the Asante ruler Nana Yaa Asantewaa led her army in rebellion against British colonial rule.

You may also like:

The further we dive into prehistory, the more varied forms of social organisation we see. At the 9,000-year-old site of Çatalhöyük in southern Anatolia in modern-day Turkey, once described as the oldest city in the world for its size and complexity, almost all the archaeological data points to a settlement in which gender made little difference to how people lived.

“Most sites that archaeologists dig, you find that men and women, because they have different lives, they have different food and they end up with different diets,” according to archaeologist Ian Hodder at Stanford University, who led the Çatalhöyük Research Project until 2018. “But at Çatalhöyük you don’t see that at all.” Analysis of human remains suggests that men and women had identical diets, spent around the same amount of time indoors and outdoors, and did similar kinds of work. Even the height difference between the sexes was slight.

Women weren’t invisible, either. Excavations of this and other sites dating to around the same time have unearthed an abundance of female figurines, now filling the cabinets of local archaeological museums. The most famous of these is the Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük, today behind glass at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. It depicts a woman sitting upright, her body deeply indented with age and glorious rolls of fat spilling out around her. Underneath her resting arms appear to be two big cats, possibly leopards, looking straight ahead as though she had tamed them.

The Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük – an early female ruler (Credit: Museum of Anatolian Civilisations/Wikimedia Commons)

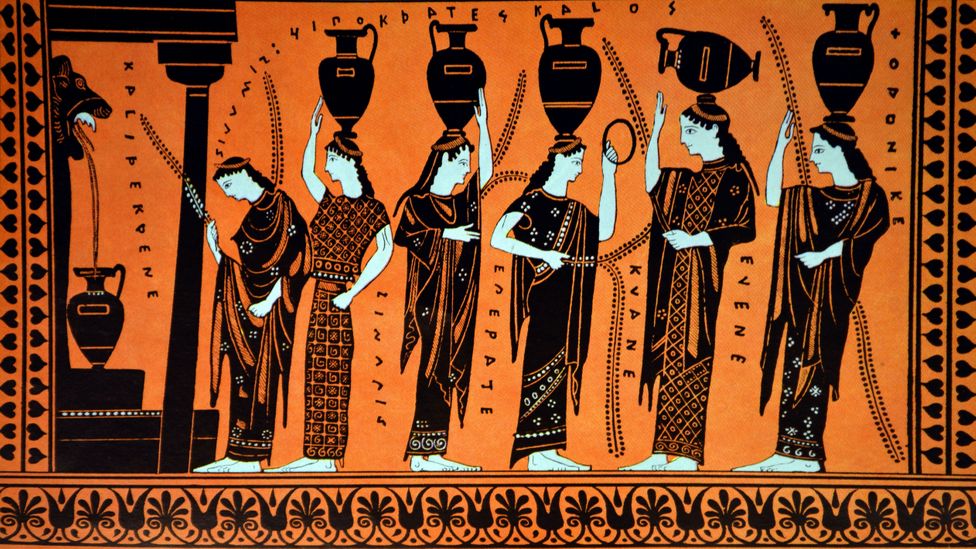

As we know, the relatively gender-blind way of life at Çatalhöyük didn’t continue forever. Over thousands of years, social hierarchies gradually crept into this broader region, which spans modern-day Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Thousands of years later, in cities like ancient Athens, entire cultures had developed around misogynistic myths that women were weak, not to be trusted, and best confined to the home.

The big question is why.

Anthropologists and philosophers have asked whether agriculture could have been the tipping point in the power balance between men and women. Agriculture needs a lot of physical strength. The dawn of farming was also when humans started to keep property such as cattle. As this theory goes, social elites emerged as some people built up more property than others, driving men to want to make sure their wealth would pass onto their legitimate children. So, they began to restrict women’s sexual freedom.

The problem with this is that women have always done agricultural work. In ancient Greek and Roman literature, for example, there are depictions of women reaping corn and stories of young women working as shepherds. United Nations data shows that, even today, women comprise almost half the world’s agricultural workforce and are nearly half of the world’s small-scale livestock managers in low-income countries. Working-class women and enslaved women across the world have always done heavy manual labour.

More importantly for the story of patriarchy, there was plant and animal domestication for a long time before the historical record shows obvious evidence of oppression based on gender. “The old idea that as soon as you get farming, you get property, and therefore you get control of women as property,” explains Hodder, “is wrong, clearly wrong.” The timelines don’t match up.

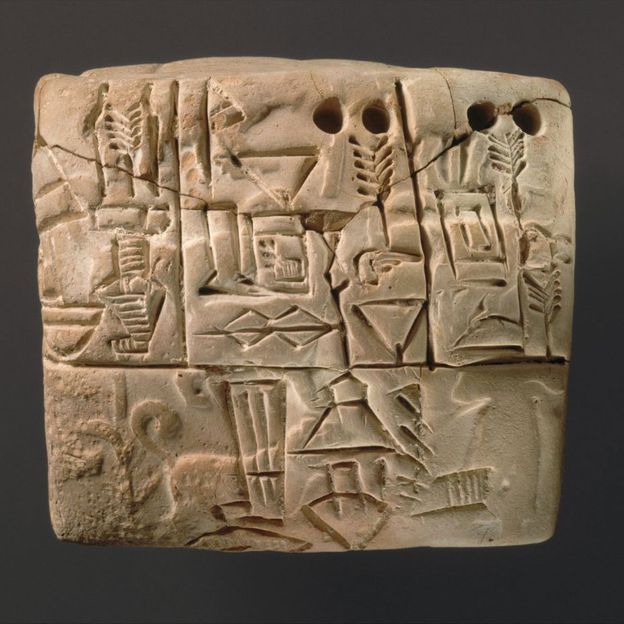

A Mesopotamian cuneiform tablet from Uruk, featuring an impression of a male figure, hunting dogs, and boars (Credit: Getty Images)

The first clear signs of women being treated categorically differently from men appear much later, in the first states in ancient Mesopotamia, the historical region around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Around 5,000 years ago, administrative tablets from the Sumerian city of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia show those in charge taking great pains to draw up detailed lists of population and resources.

“Person power is the key to power in general,” explains political scientist and anthropologist James Scott at Yale University, whose research has focused on early agrarian states. The elites in these early societies needed people to be available to produce a surplus of resources for them, and to be available to defend the state – even to give up their lives, if needed, in times of war. Maintaining population levels put an inevitable pressure on families. Over time, young women were expected to focus on having more and more babies, especially sons who would grow up to fight.

The most important thing for the state was that everybody played their part according to how they had been categorised: male or female. Individual talents, needs, or desires didn’t matter. A young man who didn’t want to go to war might be mocked as a failure; a young woman who didn’t want to have children or wasn’t motherly could be condemned as unnatural.

As documented by the American historian Gerda Lerner, written records from that time show women gradually disappearing from the public world of work and leadership, and being pushed into the domestic shadows to focus on motherhood and domestic labour. This combined with the practice of patrilocal marriage, in which daughters are expected to leave their childhood homes to live with their husbands’ families, marginalised women and made them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse in their own homes. Over time, marriage turned into a rigid legal institution that treated women as property of their husbands, as were children and slaves.

Greek pottery, dated to 400BC, depicting women collecting water for a bride (Credit: Getty Images)

Rather than beginning in the family, then, history points instead to patriarchy beginning with those in power in the first states. Demands from the top filtered down into the family, forcing ruptures in the most basic human relationships, even those between parents and their children. It sowed distrust between those whom people might otherwise turn to for love and support. No longer were people living for themselves and those closest to them. Now, they were living in the interests of the patriarchal state.

A preference for sons is still a feature of traditionally patriarchal countries today, including India and China, where the bias has led to such high rates of female foeticide that sex ratios are grossly skewed. The 2011 Indian Census showed it had 111 boys for every 100 girls, although data suggests these figures are improving as social norms change in favour of daughters.

Exploitation of women within patriarchal marriages continues. Forced marriage, the most extreme version of this, was designated a form of modern-day slavery by the International Labour Organization in its statistics for the first time in 2017. The most recent estimates, from 2021, indicate that 22 million people globally live in forced marriages.

The lasting psychological damage of the patriarchal state was to make its gendered order appear normal, even natural, in the same way that class and racial oppression have historically been framed as natural by those in power. Those social norms became today’s gender stereotypes, including the idea that women are universally caring and nurturing and that men are all naturally violent and suited to war. By deliberately confining people to narrow gender roles, patriarchy disadvantaged not just women, but also many men. Its intention was only ever to serve those at the very top: society’s elites.

Like Monkey Hill at London Zoo in the 1920s, then, this is a warped system, one that has fostered distrust and abuse. Movements for gender equality across the world are symptoms of the social tension humans have been living with in patriarchal societies for centuries. As the political theorist Anne Philips has written, “Anyone, given half a chance, will prefer equality and justice to inequality and injustice.”

As daunting as the struggle against patriarchy may feel at times, though, there is nothing in our nature that says we can’t live differently. A society made by humans can also be remade by humans.

*Angela Saini is a science journalist and author of four books. This essay is based on her latest, The Patriarchs: How Men Came to Rule, which was recently shortlisted for the Orwell Prize.

May 4th 2023

News – 19 April 2023 18:17

Woman jailed following fatal stabbing in Croydon

A woman has been jailed for the murder of her partner in Croydon.

Kamila Ahmad, 24 (10.08.98) of Robinhood Lane, Mitcham appeared at Croydon Crown Court on Wednesday, 19 April where she was sentenced to a minimum of 23 years after earlier being found guilty of fatally stabbing 19-year-old Tai Jordan O’Donnell.

At the same trial, she was also found guilty of causing grievous bodily harm on another man in 2015 and was sentenced to seven years, to be served concurrently.

Detective Sergeant Dave Brooks, from the Specialist Crime Command, said: “Tai was a much-loved son and brother and his death has left his family completely devastated and their lives will never be the same and our thoughts remain with them.”

On 3 March 2021, police and the London Ambulance Service were called to a stabbing at a flat on Alpha Road in Croydon.

On arrival, officers found a man – later identified as Tai – laying on the sofa with several stab injuries, he was pronounced dead at the scene having been injured some hours before the alarm was raised. His cause of death was later confirmed as severe blood loss due to a wound to the left thigh.

Blood pools were discovered throughout the property as well as outside the entrance. It was clear that Tai had been moved whilst seriously injured but no call for help was made. Efforts had been made to clean the scene as evidenced by the increased presence of cleaning fluids and blood stained bedding, clothing and trainers piled at the washing machine.

Detectives from the Met’s Specialist Crime Command immediately launched a murder investigation and Ahmad was arrested two days later, claiming she knew nothing about Tai’s death.

When officers searched an address linked to Ahmad, they found items discarded by Ahmad including a bloodstained rucksack and jacket. When forensically tested, they were found to be a DNA match to Tai.

The court heard that Ahmad had also carried out a knife attack on another man almost six years before the murder, in July 2015, following an argument over a remote control. The victim, Ahmad’s then partner, was stabbed three times before being moved into the street in an attempt to mislead police into believing that he had been attacked by an unknown third party. He did not initially wish to proceed with a prosecution against Ahmad but upon hearing of the murder of Tai felt compelled to support the investigation.

Hearing the parallels of the two offences enabled the jury to reject a claim of self-defence made by Ahmad who had inflicted the same behaviours and violence upon both partners.

DS Brooks, added: “We wish to reaffirm that the Met will take all instances of domestic abuse seriously and urge anyone living with violence no matter what their gender to seek help.”

Subjects

Categories

Metropolitan Police

Media Enquiries: Contact 0207 230 2171 or press.bureau@met.police.uk

April 25th 2023

Women now dominate the book business. Why there and not other creative industries?

April 4, 20236:31 AM ET

Mohamed Hassan/Pixabay

Ever since she was a little girl, Jessie Gaynor has had a passion for books. Whether classic literature or YA fiction, she spent her youth devouring novels. She wouldn’t just read them. She would reread them, sometimes the same book over and over again.

“My mom used to say that my rereading of books worried her because she thought I wasn’t expanding my horizons enough,” Gaynor says. “And, later, in retrospect, she decided that what I was doing was learning the language of the books.”

In the sixth grade, Gaynor read Angela’s Ashes. She loved the book so much, she actually looked up the author in the phone book and called him to talk about it. She got his answering machine and didn’t talk to him, but she self-mockingly tells the story as an early example of her literary enthusiasm.

Gaynor carried this enthusiasm for books into adulthood. She’s now a Senior Editor at Literary Hub, an online publication that focuses on literary fiction and nonfiction. And, just recently, she’s become an author herself.

This June, publishing powerhouse Penguin Random House is set to publish Gaynor’s first novel, The Glow. It’s a dark comedy that centers on a struggling publicist named Jane Dorner who, in a desperate effort to save her job, tries to land a lucrative client: an enchanting wellness guru. “Jane decides that she will try to aggressively monetize this woman’s shtick,” Gaynor says.

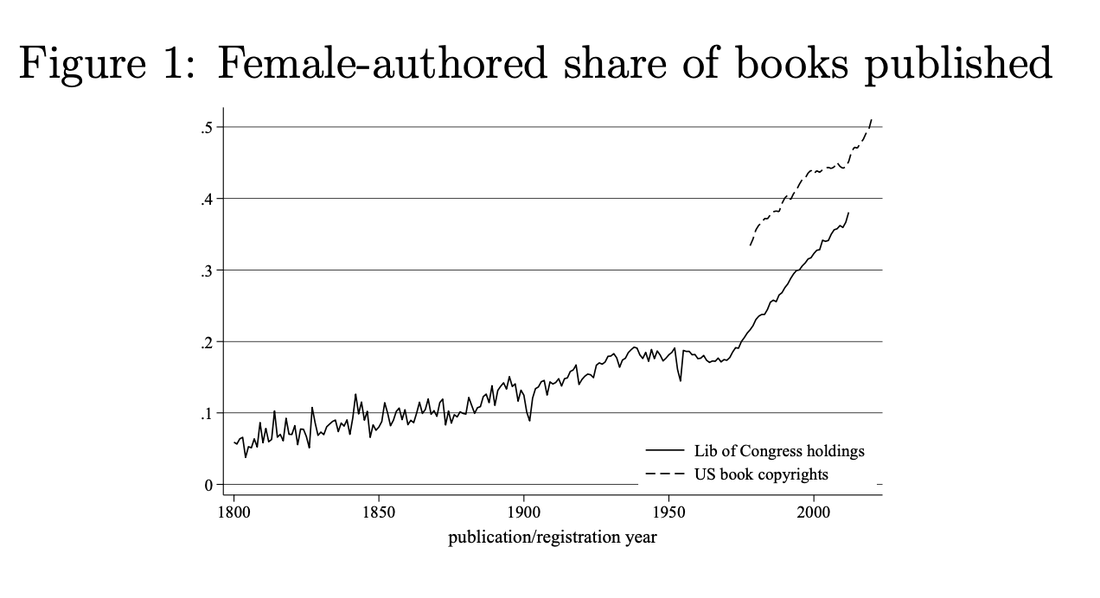

Gaynor is part of a sea change in book publishing that has seen women surge ahead of men in almost every part of the industry in recent years. Once upon a time, women authored less than 10 percent of the new books published in the US each year. They now publish more than 50 percent of them. Not only that, the average female author sells more books than the average male author. In all this, the book market is an outlier when compared to many other creative realms, which continue to be overwhelmingly dominated by men.

These findings and others come from a new study by Joel Waldfogel, an economist at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management. Waldfogel crunches the numbers on the book market’s female revolution. And, in a recent interview, the economist helps us think through potential reasons why women trail men in many creative industries, but have had spectacular success in achieving — in fact, surpassing — parity with men in the US publishing business.

Author Jessie Gaynor

Ebru Yildiz/Jessie Gaynor

Female Authors Leap Ahead

Waldfogel got interested in studying female representation in creative industries after spending part of last year at the U.S. Copyright Office as a visiting scholar. The federal agency, which is part of the Library of Congress, is tasked with keeping records on copyrighted materials.

One of the first projects the Copyright Office had Waldfogel work on was a data analysis of the evolution of women in copyright authorship. Looking at the numbers, Waldfogel’s eyes opened wide when he realized that women have seen incredible progress in book authorship but continue to lag in other creative realms.

For example, while they have made inroads in recent years, women still accounted for less than 20 percent of movie directors and less than 10 percent of cinematographers in the top 250 films made in 2022. Likewise, when looking at the data on patents for new inventions, women make up only between 10 to 15 percent of inventors in the US in a typical year.

For a long time, the book market saw a similar disparity between men and women. Sure, some rockstar female authors come to mind from back in the day: Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, Emily Dickinson, Agatha Christie, Zora Neale Hurston — to name just a few prominent ones. But, Waldfogel says, between roughly 1800 and 1900, the share of female authors hovered around only 10 percent each year.

In the 20th century, female authorship began to slowly pick up. By the late 1960s, the annual percentage of female authors had grown to almost 20 percent.

Then, around 1970, female authorship really began to explode. “There was a sea change after 1970,” Waldfogel says.

The boom in female authorship

Joel Waldfogel/NBER

By 2020, Waldfogel finds, women were writing the majority of all new books, fiction and nonfiction, each year in the United States. And women weren’t just becoming more prolific than men by this point: they were also becoming more successful. Waldfogel analyzes data from a whole range of sources to come to this conclusion, including the Library of Congress, the U.S. Copyright Office, Amazon, and Goodreads. Waldfogel finds that the average female-authored book now sees greater sales, readership, and other metrics of engagement than the average book penned by a male author.

Why 1970?

The progress women have made in the book market can be seen as one small part of the broader feminist movement. Picking a single year as a clear turning point for any social movement can get pretty arbitrary. Dramatic social changes often proceed incrementally, not in one fell swoop. That said, if you were to pick one single year as an inflection point, 1970 is a pretty good one for the women’s movement, not just in book publishing, but in a whole range of social and economic pursuits.

Female participation in the overall US labor market seems to have really picked up steam after 1970 (although, to our point, you can clearly see the antecedents for this progress beforehand). Economists have offered various theories and evidence for why, after centuries of playing second fiddle in the labor market, American women made significant advances. The lasting effects of women entering the labor force as men fought overseas during WW2, the feminist movement, cultural change, and declining discrimination surely played important roles.

So did the increasing diffusion of labor and time-saving technologies, like electricity, plumbing, dishwashers, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and microwaves, which changed the economic calculus for many families. Before households adopted widespread use of these technologies, domestic work was much more burdensome than it is now, requiring hours and hours of labor per day. The bulk of that work was done by women. As new technologies decreased that workload, various economic studies suggest, women were increasingly freed to pursue careers — including careers in publishing.

The birth control pill, which exploded in use during the 1960s, and increased abortion access in the 1970s, also helped free women to enter domains traditionally dominated by men, by giving more women greater choice over if or when to have children, and how many.

Intimately related to the pursuit of writing books, women began investing more and more in education around 1970. “If you look at the share of women who are going to college, it looks very similar to book publishing,” Waldfogel says.

It’s probably no coincidence that, by 2020, women weren’t only the majority of book authors, they had also become the majority of college graduates in the United States. Women also now represent around 70 percent of high school valedictorians every year.

But why has the book market seen so much more progress than other industries?

Despite progress over the last half century, however, women continue to lag behind men in many parts of the labor market, including many creative industries. Why are books different?

The answer matters not just for women, but for society at large. With women continuing to represent less than 15 percent of inventors in the US, to give one glaring example, Waldfogel worries that there are likely a whole bunch of “Lost Marie Curies” out there who could be helping us find cures for diseases or creating innovative, new technologies. But something seems to be holding them back. The reason why the book market has seen so much more progress might help us figure out how to replicate the success there in other domains.

However, lacking hard evidence, Waldfogel’s new study offers no rigorous explanation for why the book market revolutionized while others saw limited progress.

Waldfogel says his best guess for why women have seen so much progress in book publishing in the US, as opposed to other creative domains, has to do with the reality that the process of book-writing is typically a solo endeavor, in which the author has more power to choose when and how to do the work.

Maybe the fact that book writing is done mostly alone means there is less discrimination and fewer female-disadvantaging biases and social dynamics in the industry. Industries like movie production and scientific and technological inventing are dominated by gigantic corporate bureaucracies, which are intensely hierarchical. They also are more capital intensive. Maybe that opens the door to more sexism and a resistance to investing in historically underrepresented creators like women.

But American publishing, while seeing huge growth in self-publishing in recent years, also continues to be dominated by large corporations, like NewsCorp and Amazon. There is a twist, however, which is that individual publishing houses in the US — unlike film, TV and other creative production organizations — are largely dominated by women. In 2015, the publisher Lee & Low Books surveyed the staff at 34 US-based publishers and 8 review journals. They found that, while the industry is disproportionately white, it’s also disproportionately female. About 78 percent of staffers at all levels and 59 percent of executives in the publishing industry identified as women in the survey.

In her process of writing The Glow and getting to know the book publishing industry through her work at Literary Hub, Gaynor says, she’s seen this herself. “In my work, I encounter a lot more women who work in publishing, and I think it makes sense that women editors and women publicists are very happy to read books by other women and buy them,” she says.

The demand for books in the US is also disproportionately driven by women. Surveys over at least the last couple decades have consistently found that American women are more likely to read books than American men, especially when it comes to fiction.

Gaynor says some of the most famous channels in which books gain popularity in the US are run by women. She points to Oprah’s Book Club and Reese’s Book Club (which is helmed by Reese Witherspoon). “Even TikTok, with the popular BookTok videos, my sense is it’s mostly women — and BookTok is driving sales hugely right now,” Gaynor says.

Beyond the demographics of book readers and publishers, the social dynamics of the book writing business could be more favorable for women than other creative industries. For example, it is a generally solitary affair that lacks the office politics, practices and hierarchies that can still all too often leave women at a disadvantage.

“We hear a lot about women being socialized to not take the lead, not make a fuss,” Gaynor says. Other creative pursuits — like movie directing, for example — may reward self-confidence and assertiveness, traits that research suggests is more associated with men, on average. “I have a personality that is — I don’t know if I can blame this on my gender socialization — but I don’t like to feel like I’m bothering people. One of the great things about publishing a book is that you get an agent who bothers people on your behalf. Also, the solo part of writing a book is also very appealing because you just get to write the book and then put it in someone else’s hands. You have to advocate for yourself to a certain extent, but the work is not about being loud, which I know for some women, at least like me, that can be an uncomfortable thing.”

A growing body of research in economics points to something more than personality traits and interests that separate men and women in the labor market. The Harvard economist Claudia Goldin has published influential research that suggests one central culprit behind gender inequality in the labor market: the reality that women continue to bear the overwhelming burden of caregiving responsibilities in many couples. As a result, Goldin finds, women, on average, show greater demand for “temporal flexibility.” That is, they put a greater premium on jobs that offer flexibility in their work schedule. These jobs tend to offer smaller paychecks, but they also allow more time and flexibility to spend on unpaid domestic work at home.

Gaynor is quick to point out that, for most authors — and for fiction authors, in particular — writing a book is a “really low-paying field.” That may dissuade more men, on average, from aspiring to pursue a writing career. “I know women are driven by a number of market forces, but I do feel like it seems possible that more women would be more willing to work in a low-paying field at first.”

At the same time, book writing, for the most part, offers the ultimate in temporal flexibility, to use Claudia Goldin’s terminology. You can write a book whenever — morning, afternoon, or night. That may be particularly attractive to some women, who are more likely to be saddled with domestic work. And it might put men and women on a more equal footing in the industry. Unlike being a corporate lawyer or executive or inventor, writing doesn’t place a large premium on being available to work at all hours, which entails a greater sacrifice of your family life.

Gaynor says she mostly wrote her book before having her kids, waking up early to write before starting work at her day job. After having her first child, she says, she did have to spend a significant amount of time addressing edits from her editor and finalizing her book. But, she says, her editing process “was facilitated by my husband doing more of the childcare in the mornings.”

Whatever the reasons for the boom in female authorship, Waldfogel says that readers of all kinds, not just women, are clearly benefiting from it. And so are we, with new books like The Glow, which will be on bookshelves on June 20.

April 24th 2023

Book preview

28/259 pages available

About

5/5Waterstones4.6/5Amazon UK4.4/5Goodreads

87% liked this book

Google users

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men is a 2019 book by British feminist author Caroline Criado Perez. The book describes the adverse effects on women caused by gender bias in big data collection. Wikipedia

Originally published: 25 June 2019

Author: Caroline Criado-Perez

Nominations: Goodreads Choice Awards Best Science & Technology

How Black Women Brought Liberty to Washington in the 1800s

A 2021 book shows us the capital region’s earliest years through the eyes and the experiences of leaders like Harriet Tubman and Elizabeth Keckley

- Karin Wulf

Photo by MPI / Stringer / Getty Images

A city of monuments and iconic government buildings and the capital of a global superpower, Washington, D.C. is also a city of people. Originally a 100-square-mile diamond carved out of the southern states of Maryland and Virginia, Washington has been inseparably tied to the African-American experience from its inception, starting with enslavement, in part because of commercial slave-trading in Georgetown and Alexandria. In 1800, the nascent city’s population topped 14,000, including more than 4,000 enslaved and almost 500 free African-Americans.

Before the Civil War, Virginia reclaimed its territory south of the Potomac River, leaving Washington with its current configuation and still a comparatively small city of only about 75,000 residents. After the war the population doubled—and the black population had tripled. By the mid-20th century Washington DC had become the first majority-black city in the United States, called “Chocolate City” for its population but also its vibrant black arts, culture and politics.

In a 2021 book, At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, & Shifting Identities in Washington, DC, historian Tamika Nunley transports readers to 19th-century Washington and uncovers the rich history of black women’s experiences at the time, and how they helped to build some of the institutional legacies for “chocolate city.” From Ann Williams, who leapt out of a second story window on F Street to try and evade a slave trader, to Elizabeth Keckley, the elegant activist, entrepreneur, and seamstress who dressed Mary Todd Lincoln and other elite Washingtonians, Nunley highlights the challenges enslaved and free black women faced, and the opportunities some were able to create. She reveals the actions they women took to advance liberty, and their ideas about what liberty would mean for themselves, their families, and their community.