The Covid situation has focused -or should have – the Western Consumerist masses on the Third World. The term Third World has been replaced by smug western elite media by the euphemism ‘The Developing World.’ A rose by any other names would smell as sweet. So renaming the Third World does not hide the all pervading stink of corruption and exploitation.

R,J Cook

Africa , with massive resources, ruled by corrupt dictators ,is the world’s second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. Africa’s population will double by 2050. The average African woman has 15 children. Disease is rife and endemic. At about 30.3 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth’s total surface area and 20% of its land area. With 1.3 billion people as of 2018, it accounts for about 16% of the world’s human population. WikipediaArea: 30.37 million km²Population: 1.216 billion (2016)Largest city: Lagos

June 22nd 2022

White Lies

‘COVID will come back to haunt us from Africa’ (msn.com)

Comment on above. The comfortable white and black rich elite have exploited the George Floyd police murder to amplify BLM and divert attention from facing the truth about Africa and the western World’s black negroid culture. Ordinary blacks are being encouraged to scapegoat poor whites – leading to white resentment because it is offensive nonsense to blame all whites for slavery and calling them privileged.

No doubt vaccine take up is troubled in Africa due to fertility and religious issues. That does not mean that vaccines are the answer. Africa like the whole third world and Latin America is obsessed with religion and the after life. The rich like this trick and used it n the poor whites during the Industrial Revolution. Overpopulation encourages disease , but the elite want the cheap labour. They also used it to divide and rule their empires.

R J Cook

Democracy Now! <digest@democracynow.org>

The South African

www.thesouthafrican.com

The South African

English-language South African daily online newspaper

The South African is an English-language South African online news publication created in March 2003 by the multinational media company, Blue Sky Publications, and it operates as an online news and lifestyle publication with offices in South Africa and the United Kingdom. The publication started as a London-based broadsheet newspaper aimed at providing news for South Africans living in London.

THE IMPACT OF RACIAL INEQUALITY IN SOUTH AFRICA – July 29th 2021

The World Bank recently released a 147-page report extensively detailing the root causes of economic struggle in South Africa. Researchers found that one of the most prominent factors behind poverty is racial inequality in South Africa.

Apartheid, the government-enforced segregation and discrimination against non-white people, came to an end in 1994 with the introduction of a racially mixed, democratically elected parliament under the leadership of Nelson Mandela. But although discriminatory policies stopped being imposed by the government, that unfortunately does not mean that racism vanished from the country. In fact, South Africa remains the most racially unequal country in the entire world.

The residual effects of apartheid have had tremendous impacts on the poverty rate, and the remnants of racial inequality in South Africa are still playing a role in the nation’s economic structure to this day.

Employment Disparities Remain After the End of Apartheid

Because apartheid took place relatively recently, many non-white people in South Africa who lived through it are still recovering from being discriminated against during that time. The report states that non-whites statistically have fewer skills, simply because they were excluded from the workforce for so long. This means that they are still more likely to be unemployed than white people. In fact, black South Africans saw a 31.4 percent unemployment rate in 2017, while among white South Africans the rate was only 6.6 percent.

Employment is hard to come by for non-whites because of how the education system was set up during apartheid. White education focused on reading, language and math, while non-white education mainly trained people to become unskilled laborers so that white people would not have to compete with non-white people for high-paying jobs.

This plan worked exactly as it was intended to, and many non-white people are doomed to a life of working low-paying jobs simply because they were never taught the skills to advance in their careers. As of last year, white South Africans still bring in an average income that is five times greater than that of black South Africans.

Race-Based Displacement Caused Lasting Inequality

Another measure taken to promote racial inequality in South Africa during apartheid was the passage of the Group Areas Act of 1950. This resulted in millions of people being forced out of their homes and sent to live in specific areas based on their race. White people were able to live in the most developed areas, while non-whites were usually placed in barren rural townships. Even if non-whites happened to live in decent areas, their neighborhoods could be demolished to make room for white residences if the land appealed to them.

Because of this mass displacement, many non-whites still live far away from developed regions (even though it is no longer mandated by law) because it is too difficult to find somewhere else to live. For instance, the Western Cape province–home to Cape Town, one of South Africa’s biggest tourist destinations–is the most developed province in South Africa. The Western Cape has the lowest black population out of all the provinces at 32 percent. However, the Eastern Cape, South Africa’s most underdeveloped province, has the highest black population at 86 percent.

The distance from their townships into more populous cities makes it harder for non-whites to find employment in commercial areas, and even if they are able to secure a job, the cost of transportation to get there is very high. In fact, the average South African commuter spends about 40 percent of his or her income on transportation.

Government Efforts to Address Racial Inequality in South Africa

The South African government has taken measures to combat poverty related to racial inequality. The first of these was the establishment of minibus taxis, a cheaper form of public transportation from rural areas into cities. This has helped alleviate some of the cost and inconvenience that comes with living outside of populous areas.

Another important step taken by the government to overcome racism was the passage of the Employment Equity Act. This act made it illegal for employers to discriminate against their workers based on race and requires employers to promote diversity in the workplace through affirmative action programs.

Though these are great initiatives for helping those who were unfairly affected by apartheid and the racism that still lingers today, much more can be and needs to be done to reduce poverty by battling racial inequality in South Africa.

– Maddi Roy

Photo: Flickr

Issues for Africans in the West – July 29th 2021

Mental Health Issues Facing the Black Community.

From Ramya Murugesh

By sharing this resource and others, we can help start a conversation about how racism and discrimination affect the mental health of the African-American community. We can help to reduce the shame and stigma sometimes associated with mental illness and mental health treatment in the Black community.

For example, did you know that:

- Black Americans are 20% more likely to experience serious mental illness?

- 17% will develop a substance abuse disorder?

- Just 1/3 will receive the help they need? (The resource includes several free or low-cost mental health treatment options.)

Amidst everything going on in our world today, this is a heavy topic and relevant to many.

If you want to learn more, please check out our link and feel free to include it on your page if it would be beneficial:

Mental Health Issues Facing the Black Community

The following universities have already shared our guide:

- Columbia University

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of Minnesota

May 1st 2023

FGM in Sierra Leone: I believe my girlfriend died because her genitals were cut

- Published

- 11 hours ago

By Tamasin Ford

BBC Africa Eye

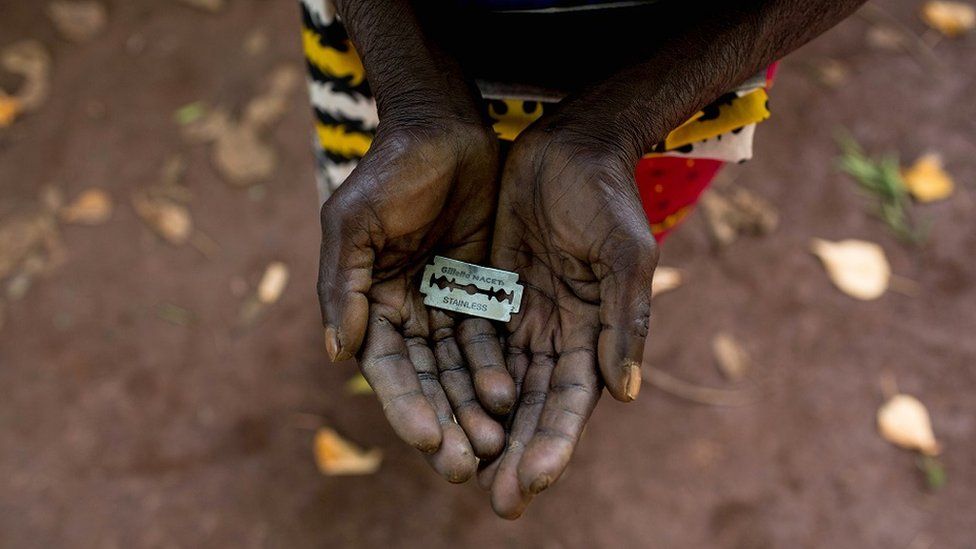

Sierra Leone has one of the highest rates of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Africa and it can sometimes end in tragedy. BBC Africa Eye has been hearing from one man who believes his girlfriend died after having her genitalia cut.

Fatmata Turay was 19 years old when her mother called her to come home to their village.

She was to be initiated into the Bondo society, a centuries-old tradition involving music and dancing where young women are prepared for adulthood.

Thirty-six hours later, Fatmata was dead.

From the day of her funeral on 18 August 2016, her boyfriend, journalist Tyson Conteh, took out his camera and started filming.

In a later recording he looked straight down the barrel of the lens to explain why he wanted to document what was happening.

“I want to use this film, which is so much passionate to me, to create a debate. Fatmata does not want to see another girl, a woman, die. That’s her wish.”

He said Fatmata had been speaking to him in his dreams, and wanted him to expose the truth of her death and put an end to the practice of FGM.

FGM involves the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, often focusing on the clitoris.

The United Nations Population Fund has documented the practice in 92 countries, but it is most prevalent in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

In countries like Somalia, Sudan and Djibouti, a form of FGM called infibulation is practised where the labia is removed and then used to almost completely seal the vaginal orifice, leaving a small opening for urine and menstrual blood. When the woman marries, they must be cut open before they can have sex.

There are no health benefits to FGM. The World Health Organization warns it can lead to urinary, vaginal and menstrual problems, as well as complications during childbirth and death.

In Sierra Leone, it is estimated that 83% of women and girls aged between 15 and 49 have undergone FGM.

One of the main reasons for the procedure is to tame a women’s sexual desire. If they are “cut”, it is thought it will protect their virginity and once they are married, they will remain faithful to their husband.

“An uncut woman loves sex more than a cut woman. That’s why we reduce the urge in them,” said Aminata Sankoh, a soweis, the name given to the women who perform the cutting in Sierra Leone.

‘It took me a week to urinate’

Conteh got rare access to film the all-female Bondo society, an age-old bedrock of beauty, art and culture.

It is a celebration where the traditional role of a wife and mother is conferred from Bondo elders to young women.

It is seen as an expected and necessary rite of passage.

However, part of the initiation process is undergoing FGM. Conteh was not allowed to film this.

“In our culture, our people have for a long time been initiated into the society,” said Ngaima Kamara, a leading soweis.

“If you are not initiated, you will be ashamed of washing with me at the stream. If I pass by you, I will blank you. If we meet somewhere I can tell you I do not talk to an uncut woman. Like you are sick.”

In his documentary, Conteh recounted what happened to Fatmata just over a day after attending the Bondo ceremony.

“We met her body laid on a mat, just outside the house in the floor. And it was wrapped in white,” he said.

“You see the blood coming out. You see like there is blood and we realised that she had died in the Bondo society after she was mutilated.”

The police arrived and Fatmata’s body was taken to the mortuary in Makeni.

Her mother and the soweis were arrested.

Six days later, a post-mortem was carried out by Sierra Leone’s only pathologist at that time, Dr Simeon Owizz Koroma.

Also present was Dr Sylvia Blyden, the then minister for social welfare, gender and children’s issues.

Dr Blyden is a supporter of the right of consenting adult women to practise FGM but is strongly against underage and forced FGM.

In a public statement, she released details of the post-mortem and said FGM had nothing to do with Fatmata’s death. The soweis and Fatmata’s mother were released.

Conteh investigated the possibility of whether his girlfriend’s death was covered up to protect the Bondo society. Dr Blyden maintains she would never substitute the truth over the reputation of the Bondo society.

Rugiatu Turay, no relation to Fatmata Turay, was Dr Blyden’s deputy minister at the time and is a long-time campaigner against FGM.

She founded and runs the Amazonian Initiative Movement, an organisation in Sierra Leone focused on ending FGM.

She said she was lucky to survive after she was cut when she was 11 years old.

“Plenty people have died. We know, we all know. We should be honest,’ she said.

“I almost died. If I wanted to pee. It took me a week to be able to urinate. One week. Even after initiation ended, my vagina swelled.”

‘Bondo will end’

Ms Turay questioned why Dr Blyden was present at the post-mortem.

“Why do you allow your minister to go into a mortuary to do a post-mortem? Even if she is a doctor, she has no business there.

“She stood with the soweis. That shows that she already took sides. We believe that the result, which we never saw, was changed. We believe that. We cannot bargain the lives of women for votes.”

Dr Blyden denied speaking publicly about Fatmata’s cause of death but stands by her claim that Fatmata did not die as a result of FGM, saying the findings of the post-mortem matched Fatmata’s medical history.

She said any suggestion of a cover-up was false and malicious and added that the autopsy was conducted in full view of family, human rights organisations, police and medical personnel.

She argued that it was her duty as a minister to attend the autopsy and denied she was there for any political gain.

BBC Africa Eye approached Dr Owizz with the allegations in the film, but he declined to respond.

Four years ago, Ms Turay set up the first Bondo society without FGM, called Alternative Rites or Bloodless Bondo.

She believes that the Bondo itself could end if women do not stop practising FGM.

“If women or anybody continues to advocate the cutting in Bondo, it will reach a point when Bondo ends. It will reach a point where Bondo will stop.”

You can watch the full BBC Africa Eye documentary, FGM: For the love of Fatmata here.

Related Topics

- What is FGM, where does it happen and why?

- 6 February 2019

- Female genital mutilation was my ‘reward’

- 26 June 2021

- My mother said ‘forgive me’ for my FGM

- 9 February

July 18 2021

Three Presidents Who Opposed Covid Vaccines Have Conveniently Died, Replaced by Pro-Vaxxers

“Coincidences” always seem to favor the globalists.

by JD RuckerJuly 18, 2021 in Conspiracy Theory, Globalism, Healthcare, Opinions, Science, The Great Reset

We took a lot of heat last week for publishing an article speculating that Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated to usher in vaccines into his country. By “heat,” I’m not talking about the standard trolls or Twitter DMs. The site was hit by a massive wave of hack attempts that failed miserably. Praise God and thank you to my security firm!

The attacks are likely to ramp up after this article is released as it details the events surrounding two other world leaders who happen to have died to allow for Covid vaccines to be brought into their countries. Nobody other than Free West Media is covering it thus far; I searched even the fringiest sites I could find for a hint of speculation and it was notably missing. Maybe they don’t know. Yet. Maybe they’re fearful of the same types of attacks we suffered. Either way, we’re ready to spread the word.

[Update 1: As anticipated, the attacks came in quickly. This time, I was monitoring the traffic in real time. It’s conspicuous that before the surge of attacks, there was an odd amount of traffic coming from… wait for it… Washington DC and Fort Meade, Maryland.]

Here’s the article by Free West Media followed by my commentary:

Coincidence? Three presidents dead after blocking distribution of Covid vaccines

The leaders of three different countries died after having stopped the distribution of the experimental Covid-19 jabs. All three countries took the decision to distribute the vaccines to their citizens only after their leaders passed away.

One of them was Haitian President Jovenel Moise, who was assassinated at his home in Port-au-Prince recently by a group of mercenaries.

The Caribbean country has been eligible for free vaccines through the COVAX scheme, run by the World Health Organisation as well as global vaccine charities, but Moise had notably refused the AstraZeneca shots. Only days after his murder, the US dispatched vaccines to Haiti, together with a team of FBI agents.

This means that Haiti is now no longer the only country in the Western Hemisphere not to accept the Covid injection.

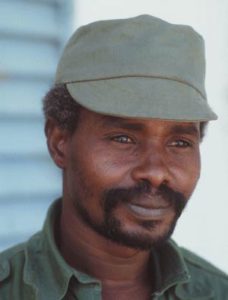

Soon after President John Magufuli of Tanzania had declared the vaccines dangerous, he passed away from a “heart ailment”. In February 2021, his health minister had told the media: “We are not yet satisfied that those vaccines have been clinically proven safe.” The death of the immensely popular Magufuli resulted in thousands of mourners crowding into a stadium to view his body. However, soon after Magufuli’s death, Tanzania ordered a huge shipment of the products worth millions of dollars for its 60 million citizens.

“You should stand firm. Vaccinations are dangerous. If the White man was able to come up with vaccinations, he should have found a vaccination for AIDS by now; he would have found a vaccination [for] tuberculosis by now; he would have found a vaccination for malaria by now; he would have found a vaccination for cancer by now,” Magufuli had warned in January, 2021.Little Did They Know They Were Being WatchedMighty ScoopsAds by Revcontent

Magufuli, a former chemistry teacher, also trashed PCR tests by demonstrating how a goat and a papaya fruit had both tested positive for Covid-19. Magufuli’s view on PCR tests is shared by the international trial lawyer Dr Reiner Fuellmich who has launched a historic class-action lawsuit in Germany and the US against Christian Drosten and the other scientists who created the PCR testing protocol used to “diagnose” Covid-19.

In November, 2020, an appeals court in Portugal had ruled that “the PCR process is not a reliable test for SARS-CoV-2, and therefore any enforced quarantine based on those test results is unlawful”. The judges, Margarida Ramos de Almeida and Ana Paramés, referred to several pieces of scientific evidence showing that in PCR tests with 35 cycles or more the accuracy dropped to three percent, meaning up to 97 percent of positive results could be false positives.

In March this year, an Austrian administrative court acknowledged the limitations of PCR and antigen testing in use currently, ruling that “PCR tests have no diagnostic value”. This view was echoed in April by a German court in Weimar, stating that PCR tests were not “suitable for determining an ‘infection’ with the SARS-CoV-2 virus”. It also ordered the lifting of various restrictions in the region.

Burundi was the second African country to reject Covid shots in February this year. The health minister of the African nation, Thaddee Ndikumana, told reporters that prevention was more important, and “since more than 95 percent of patients are recovering, we estimate that the vaccines are not yet necessary”.

Burundi’s late President Pierre Nkurunziza was harshly criticized for not advancing the notion of injections against SARS-CoV-2. Remarkably, the current President Evariste Ndayishimiye now describes the virus as Burundi’s “worst enemy”.

In the most vaccinated countries, like Israel, the UK or the Seychelles, and especially in Gibraltar which boasts a 100 percent vaccination rate, the alleged delta variant now doubles every 3 days. Perhaps the current 23 cases is not significant, but 23 cases in an area with 35 000 inhabitants is the equivalent of 45 000 cases per day in a country like France.

And it has been more than a month and a half since 100 percent of the population of Gibraltar was vaccinated with two doses. This “paradise” for the vaccinated vindicates the hesitation of the Africans to take part in the mass experiment.

Editor’s Commentary: Like I said in the opening, there is no way this is all just one big coincidence. We noted in the original article that among those accused of the assassination in Haiti were people on the FBI’s and NSA’s payrolls. Yes, the Deep State is very much directly involved in the globalist agenda surrounding these “vaccines.” Of that, there can be no doubt. Nothing at this scale happens without their direct involvement.

Freedom Just Another Name For Nothing Left To Lose – July 17th 2021

Inside the World of the Black Elite: An Interview With Margo Jefferson

43.60K

Jason Parham09/29/15 03:10PM Filed to: INTERVIEWS

Upon the publication of Lawrence Otis Graham’s Our Kind of Peoplein 1999, the New York Times asked, “Is There a Black Upper Class?” On the surface, it was a foolhardy question—of course there was, and is, a black upper class—but if you were to peel back its exterior, as Graham did in his book, underneath revealed a world of race leaders: men and women and children who were in a constant “state of self-enhancement.” Here was a place, a land, very few Americans knew about.

Pulitzer-winning writer and cultural critic Margo Jefferson’s new memoir, Negroland, maps this very terrain, one on which money, privilege, and racism intersect in sometimes insidious ways. In Negroland—what Jefferson terms “a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty”—lived the best of Afro-America: doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, teachers, and all-around strivers of the Third Race, the black aristocracy. Here in this community there were national and local clubs like Boule, Jack and Jill, the Guardsmen, Links, and black sororities and fraternities like Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Phi Alpha, founded to ensure that blacks of a certain pedigree would “embody and perpetuate the values of the Negro elite.”

Jefferson grew up in the well-to-do environs of Chicago—Bronzeville and Park Manor—the daughter of a doctor and a socialite (her father was the head of pediatrics at Provident Hospital, one of the oldest black hospitals in the country). But the cushion of Jefferson’s world would not always be so. “Nothing highlighted our privilege more than the menace to it,” she writes. A good education, expensive clothes, fancy cars, and comfort, she discovers, would not save her, or other residents of Negroland, from the terrors of the outside world.

In Negroland, Jefferson examines her own social navigations among, and in response to, the white world, and is equally critical of the cracks that splinter the foundation on which her own people stand: hierarchies based on skin color, wealth, “passing,” and status within social circles. “I’m a chronicler of Negroland, a participant-observer, an elegist, dissenter, and admirer; sometime expatriate, ongoing interlocutor,” she confesses in the book’s opening pages.

Yet despite the security of Negroland and her later successes, Jefferson admits she began to harbor feelings of depression. “Negroland girls couldn’t die outright. We had to plot and circle our way toward death, pretend we were after something else, like being ladylike, being popular, being loved… In the late 1970s, I began to actively cultivate a desire to kill myself.” This admission, and others, is a reminder that the everyday realities for those living within the world of the black bourgeoisie were far from pristine.

I recently spoke with Jefferson via phone.

The black aristocracy is not a subject that is often written about, especially with such a critical eye. It’s a welcome book in such an interesting time in history.

Yes. Very true. It is indeed an interesting time in history. [laughs]

Interesting is not necessarily the right word.

Well, interesting covers a range: from surprising to appalling. We can cover a lot of ground with that.

Right. So in the last decade alone: from, let’s say, the election of President Obama to the current state of black men and women getting killed at such a rapid pace. So by interesting, I guess I mean to say, the book arrives during a time of—

—what appears to be absolute progress mixed with these revelations of continuing, extending brutalities.

Did you always expect to write this book?

Not always. I started to really think about it, consciously let’s say, around 2007 or 2008. I’d worked on a couple of theater pieces through an institute that Anna Deavere Smith ran that used this material. That’s when it settled in my mind as material I could put out in the open. I did not start working on it until later. In 2008 I got a Guggenheim Fellowship; I applied and started writing it. And then life intervenes and you get slowed down, but I knew that I had to finish this.

The book operates in varying ways: it’s part social history, part memoir, part insider’s tale. When you began to seriously write Negroland, was the intention to purposefully construct it in this way?

I didn’t always know. It was only my second book. On Michael Jackson had been a book-length essay, and maybe the one thing they have in common is that they aren’t following a straightforward sequence—they move by theme and association. That structure, even in terms of reading, always appeals to me. When I thought about a memoir, and really got working, I knew I wanted it to be doubled. Meaning: a cultural memoir and a personal memoir; mapping a relationship with this world, with all of its tensions, and links to the larger white and larger black world. But I am also the character—watching, being affected—so in that way, it was a personal memoir. The world itself is so full of changes—of negotiations, changes of position, seeing things one way, then another, gauging responses, status changes that can happen in an instant. I felt the structure needed to reflect all those social shifts, political shifts, cultural shifts, and swings of mood and of status.

Let’s talk about the status within that world. You refer to the black bourgeoisie as “the Third Race.”

That’s how we thought of ourselves. And that really starts before W.E.B. DuBois. It’s modern name was the Talented Tenth, the race leaders. The people who are educated, who are cultivated. This Victorian-into-modern sense of achievement. And of also: cultivation, education, dignity. All of these things were, in today’s parlance, respectability politics. They were to prove, to refute bigotry’s claims, and to prove, as a people, we deserved equal rights and were progressing and moving and could equal the best of white people. That’s the lineage.

Growing up in Chicago, how early on did you recognize the scope of your privilege?

For a child, for the black bourgeois, the scope—and I think this is true for any group that has been discriminated against, oppressed, and whose status is always contested—varies. Within an all-black world, it felt very, very secure. How is this manifested? By material things—your house, clothes, by manners, by the schools you go to, by what your parents say to you about how you’re supposed to carry yourself in the world. It always shifts when you move into various parts of the white world. Then you are contending with much shakier status. You start learning that your privilege can be challenged or disregarded at any minute. You’re learning those things almost simultaneously.

What’s the earliest example of your security being challenged in the white world?

The earliest one I am conscious of, in fact, is when I’m in elementary school. I come home and ask my mother questions; mind you, I’m at a school I feel very comfortable in; it was a progressive school, not a lot of incidents, and I had real friends. So I say to my mother, some other student has asked me if we’re rich and upper class. I was young, and thought, Oh, how nice. I thought this was flattering. My mother’s answers made finally clear to me that what was implied—and, of course, this child didn’t know that; it was coming from the parents—was that this little Negro girl and her mother, who seems to be driving a car as nice as mine and seems to speak standardized English, were asking what kind of status did we have. You know, what kind of status do they have? I suppose in their world they are upper class. She must have overheard a lot of speculation. It was basically saying: what oddities are these people given the inferior race they’re from. That, with my mother making clear to me, we were going to be negotiating between our own world, in which we were considered upper class, the larger American world, in which we’d be considered bourgeoisie, and the world dominated by racism—by white constructs of race—in which we would just be considered a mass of Negroes that they really didn’t have want to bother with and didn’t think well of.Negroland: A Memoir

Early on you write that Negroland women wanted to be seen as ladies, not necessarily “black.” It reminded me of that Ralph Ellison passage from Invisible Man where the narrator meets Brother Jack, and Brother Jack asks, “Why do you fellows always talk in terms of race?” and he responds, “What other terms do you know?” There is a similar push and pull in the book; citizens within Negroland do not always want to be identified as black, but the world continues to push color and these constructs onto them, even as they pull away.

It’s a question of free space. There was certainly within Negroland race pride and race consciousness, along with snobbery and over identification with white values. We were always supposed to be aware that we were to help carry the race forward, but what you want is free space to simply live your life and be yourself. Everyone wants that. You don’t want to have no choice. With race consciousness—which is always problematic; yes there is race pride, but when it is being forced on you from the outside white world, you’re not controlling it, when you’re not in control of that consciousness, those questions, those criticisms—you can be turned into a sociological object, an object of scorn, a test case, at any point. You have no control over that. You have control over how you respond to it, but not over its intrusion into your life—your external life and your interior life.

This response then becomes a sort of performance.

Yes. Absolutely. Even the anticipation of it. Maybe it’s not going to happen this time, but you better be ready in case it happened. There’s a constant vigilance and weariness, and then the performance. Which, again, has to be shaded and altered according to white characters; some intrusions are very subtle and some are quite blatant.

Beauty comes up in the book often. This notion of skin color as it relates to degrees of privilege, which is really a larger conversation about ownership and who dictates what is acceptable and what is not acceptable. I imagine navigating that landscape within Negroland—with its strict guidelines of beauty and decorum—must have been more difficult that having to navigate that terrain outside Negroland.

I thought you were going to say in a different period, because it’s all more fluid and flexible and generous now. Starting with, I would say, Black Power, those very constricted standards of Anglo-Saxon beauty got challenged and pushed out. Everything started to change, change, change.

Historically, these divisions—whereby lighter was better, thinner noses; let’s just say Anglo-Saxon looks—go back several centuries. These divisions and hierarchies started as soon as blacks arrived and mingled with each other, began to intermingle with white people, and were divided into house servants, field hands, free Negroes, not. All of these markers—what color you were, what you looked liked—had huge social and political consequences. They got passed on, not surprisingly, and really ruled in a society that was Anglo-Saxon. And I say that very specifically, because other immigrant groups who register as white were also aspiring to Anglo-Saxon models. That was what you were living up to.

We’re talking about physical markers; one of the key distinguishing facts for Negroes, black people, African Americans, was that we could be judged, categorized, dismissed, or abused instantly on the ground of visibly registering as Negro in some way. These markers of skin, features, all of that, became a determinant of one’s fate. Now place that on women, and black women therefore are bringing this body of prejudice and consequence into this maniacal, rigorous world whereby women are judged by excruciating visual standards, along with manners. All of which, again, is very white and very Anglo-Saxon, and which black women had been systematically excluded from so they could in no way live up to notions of being beautiful, being a good mother, being respectable, being virtuous.

That must take a traumatic toll, psychological and physical, on the body for black women.

Well, I wouldn’t say it’s always traumatic. But it’s very demanding. It certainly has its moments. If you look at a novel like The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison; there’s an example of trauma. If you look at a novel like Quicksand or Passing by Nella Larsen there’s an element of trauma, but also there are social complications and navigations. These become stories of extremely complicated, demanding, and sometimes killing, manner.

Which sort of leads me to my next question. I want to talk about, as you write, that “sanctioned, forbidden space between white vulnerability and black invincibility.” Despite all the privileges Negroland had provided, it could not guard you from depression and thoughts of suicide.

Everyone is driven in a different way. The burden of being a constant symbol, of having to live up to a symbol of advancement, of progress, of being perfect in some way and always representing the destiny of an entire people—that is supposed to be invincibility. That’s enormous. That translates often in black life, or translated traditionally into admonishes along the lines of, No, you can’t fail; You can’t show that kind of grief or despair, depression, because it was a kind of failure.

A weakness.

It can be a major weakness if you give way to it. And it can defeat you, and it shows that they’ve won. Sometimes we even used to be told, We don’t commit suicide, we’re too strong for that. These are battle weapons, aren’t they? This sense, this charge, to be invincible, and not to give way even in private, as if momentary despair, grief, melancholy, even if giving into them for a moment, could weaken you like a toxin in your system, could render you not fit for the life battle. This was exhausting. For me, and I’m not alone in this, giving into and residing in, for real periods of despair and depression, became a kind of rest space.

What do you mean by “rest space”?

A space retreat—I’m not responsible to anything in the larger world right now. I need respite. And also: I need to acknowledge, whatever despair and depression do, the toll the grief is taking on me. I need to acknowledge the toll certain parts of my life are taking on me. I have to do that, even if it temporarily paralyzes me to suppress it. Otherwise, paradoxically, I can’t go on. When I can reside in that, and recoup, then I can continue. In a strange way it’s a survival method.

Had you not been recognizing that grief before?

As people who grapple with depression, there’s the other side—I’m vivacious, lively; as a child I had really performed. And I enjoyed the performance. Like many people, and this in not unusual, I began to discover the successfully hidden aspects of myself when I got to college. Also, let’s remember, I got to college in 1964; the world was in tumult. You were exposing yourself and revealing yourself, and throwing whatever feelings you had into all of these passionate movements and discussions; you were writ large. The world was upending, helping upend the way you’d lived before and thought before. So, of course, that leads to all kinds of inner tumult. You can’t protect the inner psyche from the changes the world is asking of you.

But even in this inner tumult, you write: “You must set an example for other Negroland girls who suffer the same way. You must give them a death they can live up to.” Amidst both internal and external changes, you still carried this sense of uprightness you’d learned as a child.

It stayed with me. But I am, as they say in literature, being bitterly ironic there. That was a moment. That was one of my temporary resolutions. I say, Ok, If I’m going to kill myself then I want that to be an example and help set a pattern that will be useful for Negro girls or black women who want to do the same. I didn’t want it to be squalid or worthless; I wanted it to be distinctive, noteworthy. Even then, I wanted to excel at it.

What are you hoping readers take away from the book?

That the work and the play, the entanglement of an individual life, with a world, with a society, with these larger forces, this constant push-pull between who are you are, the solitary character, and what the demands of the world, from your family to society, what they are are, and what’s being made between you. I hope people will also look at the power and privilege—they’re such big words, like race and gender and sex—because they manifest themselves in our lives in so many ways. I would want the book to spark readers to make those connections in their lives. We all live several lives—there’s the internal, there’s the external, there’s the life of me as a black woman, there’s the life of me as an American citizen—and we’re all doing this, and how are you faithful to those lives?

How the fall of Qaddafi gave rise to Europe’s migrant crisis – Posted July 14th 2021

Under Qaddafi, Libya worked closely with Europe to harshly stem the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean. But the country’s chaos has upended that.

Carmelo Imbesi/APSurvivors of the boat that overturned off the coasts of Libya over the weekend disembark from an Italian Coast Guard ship at Catania Harbor in Italy on Monday.

April 21, 2015

- By Dan Murphy Staff writer

Two horrible tragedies in or at least near Libya: Up to 800 migrants trying to reach Europe from Africa die after their boat sinks off the coast, and 30 migrants are murdered by the so-called Islamic State on the shore in the troubled country.

Libya’s chaos has once more made it a major way station for Africans seeking a better life, as the European Union grapples with the morality of cutting back on patrols to rescue migrants. The argument for doing less is that increasing the risk of crossing the Mediterranean would save lives. Word that there was no safety net would filter back to people, many of them fleeing persecution, and they’d stop coming.

“We do not support planned search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean,” British Foreign Office Minister Joyce Anelay said last year. Rescues have “an unintended ‘pull factor,’ encouraging more migrants to attempt the dangerous sea crossing and thereby leading to more tragic and unnecessary deaths,” she argued.

It clearly hasn’t worked out that way, as The Christian Science Monitor’s Nick Squires wrote in March:

Last year, a record 170,000 refugees flooded across the Mediterranean, traveling in large part out of Libya and arriving in Italy. In January, more than 3,500 refugees and migrants reached Italy from Libya, a 60 percent increase from January 2014. They come from all over Africa and the Middle East.

The Eritreans are fleeing a brutal regime which dragoons young men into military conscription and maintains a semi-permanent war footing with neighboring Ethiopia. Syrians and Iraqis are fleeing the war and atrocities committed by the self-described Islamic State, Palestinians the open prison that is Gaza, and West Africans the crushing poverty that has framed many of their lives … The vast majority of refugees make for Libya, where a power vacuum since the 2011 fall of dictator Muammar Qaddafi has enabled gangs of human traffickers to flourish …

“Everyone in Libya is armed now,” says Djiby Diop, a 20-year-old from Senegal who spent three months in Libya dodging gunmen. “If you don’t work for them, they shoot you. If you don’t give them all your money, they shoot you. Or they shoot you just for fun.”

In some corners of Europe, there is a callousness and contempt for the migrants. Columnist Katie Hopkins called them “cockroaches” in The Sun, Britain’s largest-circulating newspaper, on Friday.

“Show me pictures of coffins, show me bodies floating in water, play violins and show me skinny people looking sad. I still don’t care,” she wrote. “What we need are gunships sending these boats back to their own country. You want to make a better life for yourself? Then you had better get creative in Northern Africa.”In Atlanta, a glimpse of why ‘defund the police’ has faltered

The callousness is far uglier in Libya itself, where local gangs prey on migrants, and racism against darker-skinned Africans is common.

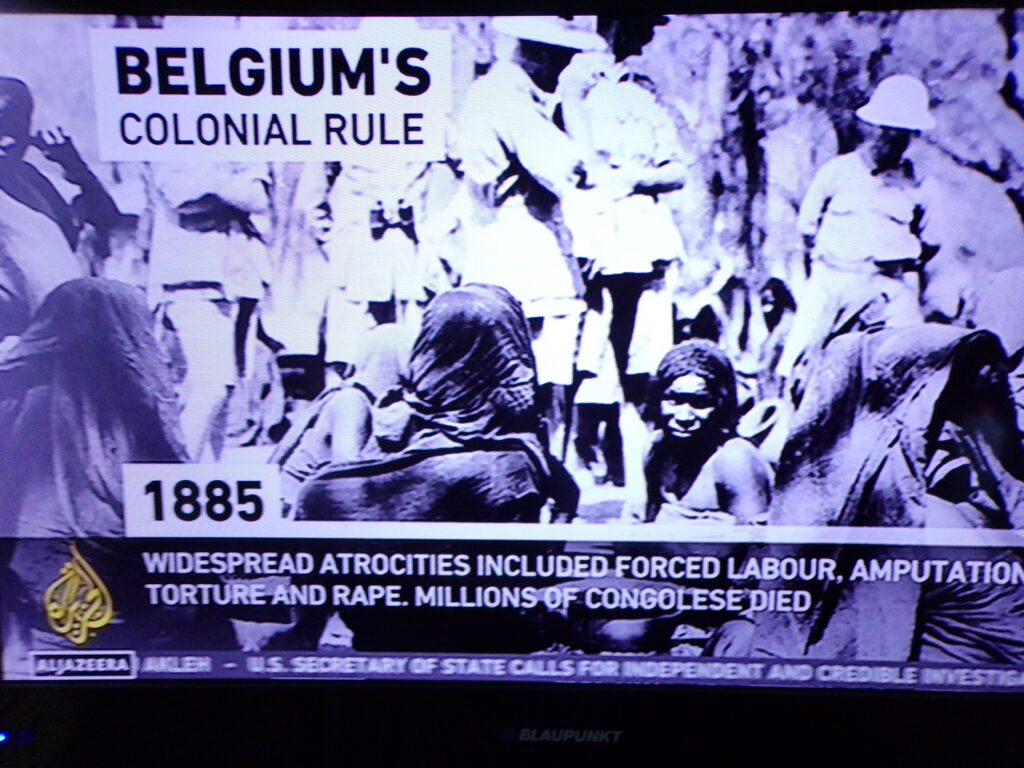

The migration crisis in its current iteration stems, in part, from the fall of Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi. In 2010, Europe was moving quickly to normalize relations with the former dictator. Oil interests played a role, but so did the desire of many European nations to outsource migrant control to the North African country.

Libya’s coast has a long history of sending people – willing and unwilling – to Europe and the Americas. Ports like Tripoli and Benghazi were the final stops for medieval slave-trading caravans from the African interior until the 19th century. In recent decades, migrants have shoved off for Italy and Spain in rickety fishing boats, with Libyan officials looking the other way.

Mr. Qaddafi was well aware of European alarm at the rising tide of migrants in his final years in power. He used it as a powerful wedge to improve his own standing. Back to 2004, Qaddafi began making deals with individual European states to control the tide of migrants. In August 2010, he visited his friend Silvio Berlusconi, then president of Italy, in Rome and said Europe would turn “black” without his help.

“Tomorrow Europe might no longer be European, and even black, as there are millions who want to come in,” Qaddafi said. “What will be the reaction of the white and Christian Europeans faced with this influx of starving and ignorant Africans … we don’t know if Europe will remain an advanced and united continent or if it will be destroyed, as happened with the barbarian invasions.”

Qaddafi had a handy solution. He offered to shut down his country and its coastal waters to the job seekers in exchange for €5 billion a year. He pointed to his work with Italy as proof he could get the job done. In June 2009, he signed a “friendship” agreement with Italy that involved joint naval patrols against migrants and Italy handing over migrants captured en route to Europe to Libya, no questions asked. The number of Africans caught trying to illegally enter Italy fell by more than 75 percent that year.

By the end of the year Qaddafi had struck a more modest €50 million deal. Internment camps were built and watchtowers erected on the beaches. There was little concern with how Qaddafi went about his business and there were frequent reports of rape and theft by Libyan security services.

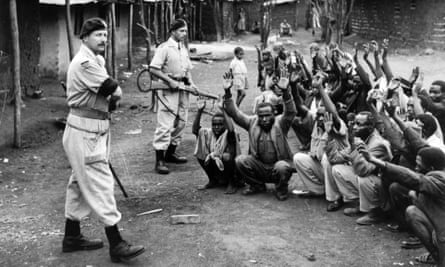

When the uprising against Qaddafi began in early 2011, the situation only grew worse for the African migrants. Many rebel groups were convinced that any foreign African in the country were mercenaries for Qaddafi and hundreds were executed. I met a group of such so-called “mercenaries” – some shoeless, all poor and underfed and insisting they were only seeking jobs – held captive by rebels outside Benghazi that spring.

In the years since, Libya’s lawlessness has made traveling through the country even more dangerous and unpredictable. The videotaped mass execution of Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants carried out by the so-called Islamic State makes that clear enough. Yet still people go, and the UN refugee agency is now calling the recent shipwreck the deadliest it has ever recorded.

10 FACTS ABOUT

CORRUPTION IN NIGERIA

– July 14th 2021

People most commonly define corruption as the “abuse of entrusted power for private gain,” and government officials and citizens feel its effects on an everyday basis. It is a growing political issue around the globe, but developing countries like Nigeria often struggle deeply to control or combat corruption. The most reliable source that measures corruption is the Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Nigeria often ranks in the bottom quartile of this index, with the scale being zero (most corrupt) to 100 (cleanest). Below are 10 facts about corruption in Nigeria.

10 Facts About Corruption in Nigeria

- Nigeria has two main political parties: the All Progressive Congress party (ADC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). These parties are almost identical in platforms but still oppose one another. Each party often increases corruption in Nigeria by utilizing misappropriated public funds to run opposing campaigns.

- A survey from 2013 showed that over 75 percent of journalists admitted to accepting financial gifts from politicians. These bribes often lead to editors and journalists manipulating stories and coverage to create media corruption in Nigeria. Despite this, the country still maintains an almost completely free press.

- Corruption in Nigeria has neither improved nor declined in score over the past several years. Typically, the country’s score varies from 25-28 any given year. Although there has not been a sharp increase or decrease, Nigeria still ranks below the average of 32 for the sub-Saharan African region.

- Former petroleum minister Diezani Alison-Madueke used a $115 million bribe to secure an election victory for the PDP in 2015. The ADP and PDP collectively spent almost $2 billion on his campaign in the same year. This spending came from public funds and contributed to higher electoral corruption in Nigeria.

- Entrepreneurs generate 50 percent of the GDP in Nigeria but often face extortion and racketeering from police forces. Federal legislators have diverted $433 billion to vague projects in the past several years. This hurts small businesses in the country and allows corruption in the government to continue.

- Before the 2015 elections, the removal and distribution of $236 billion to 24 state governors occurred without explanation. Nigeria originally opened the fund to provide inexpensive loans to small businesses in the country. As of 2018, there is evidence to suggest that this money has been almost completely embezzled throughout the years.

- Nigeria has conducted a fixed exchange rate for its currency, the naira, in hopes of preventing further inflation from corruption. The naira is currently one of the lower performing currencies in the world largely due to continuing corruption in Nigeria. This new rate has caused prices of imported goods to double and inflation to spike.

- The Buhari administration has proposed a budget with plans for investing in agriculture and mining while battling corrupt business practices. However, projects like these often consume large quantities of public funds. This appropriation of funds to industrial projects often leads to higher levels of corruption in Nigeria.

- Between 2011 and 2015, over $3.6 billion disappeared from Nigerian public coffers. Unfortunately, this stolen sum resulted in a loss of potential roads, schools and homes planned for construction. This includes a loss of 500 kilometers of potential roads and around 200 potential schools that required only one-third of the stolen funds.

- Corruption in Nigeria affects poorer families most severely. These high levels of corruption could cost individuals $1,000 per person by 2030 if the country does not address it. Further, the levels of inequality continue to increase in the country due to corruption.

The country still has many steps to take in order to successfully defeat corruption and continue developing. A presidential advisory committee has recently established to combat corruption in Nigeria. Nigeria also now legally requires banks to issue universal identification numbers to individuals. This process works by tracking multiple accounts owned by an individual and identifies missing or misappropriated funds. Citizens must speak out against corruption and governments must be held accountable in order to fully combat the issue. Additionally, governments must strengthen their institutions and close loopholes that allow for corruption in Nigeria to continue. For now, Nigeria is taking action in hopes of at least decreasing corruption in the coming years.

– Hannah Easley

Violence and Abuse Wreak Havoc in Central African Republic – July 14th 2021

By Lisa Schlein

A human rights lawyer appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council reported to the body Friday that the war-torn Central African Republic’s civilian population is being battered by both armed groups and security forces meant to protect them.

The Central African Republic has been in turmoil since rebels overthrew the government in 2013, displacing 1.2 million people. Togolese human rights lawyer Yao Agbetse was appointed by the U.N. council in 2019 to monitor and report on the human rights situation in the C.A.R.

He says the Coalition of Patriots for Change, a collection of major rebel groups, has intensified its attacks against the civilian population since March. He accuses the CPC of recruiting child soldiers, committing sexual violence and murders, illegal taxation, destruction and looting of property, and occupation of schools. He says action is being taken to hold them to account. He speaks through an interpreter

“Most of the leaders and members of the CPC are on the list of sanctions from the Security Council concerning the CAR,” Agbetse said. “The Security Council and the international community as a whole is taking the appropriate steps to ensure that these individuals can be held accountable to violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.”

What is happening in Tigray? Ethiopia’s brutal civil war explained – Posted July 14th 2021

In northern Ethiopia, millions have been displaced and thousands killed by government troops, and famine is looming

Ethiopia was, until last year, seen as one of Africa’s great recent success stories. From the mid-1990s, it started moving towards democracy, and from a state of dire poverty – in 2000, it was the world’s second poorest nation – became a model for rapid, effective development. In 2019, its prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending Ethiopia’s 20-year war with neighbouring Eritrea.

But the nation’s underlying ethnic tensions and its violent history have proved hard to escape. Tigray, Ethiopia’s northernmost region, has often been a focal point for disputes. It is home to seven million people out of Ethiopia’s 112 million: Tigrayans are the nation’s third largest ethnic group (the two largest, the Oromo and the Amhara, make up more than 60%). They have a strong local Orthodox Christian identity, and a strong sense of grievance against central government.

Witnesses in Abi Addi, in the Temben region of Central Tigray, told The Telegraph that Ethiopian federal soldiers and Eritrean troops killed a total of 182 local people in a house-to-house massacre in the town and surrounding villages.

The paper reports that most of the victims were said to be farmers, whose bodies were then “dumped in a nearby crater” until their families and village elders “begged Ethiopian soldiers to allow burials to take place”.

One survivor who escaped into nearby mountains described seeing “dead bodies scattered, bodies half-eaten by dogs”, after returning to his village.

“The soldiers did not allow anyone to get close to the corpses,” 26-year-old Tesfay Gebremedhin continued. “But later, they started to feel disturbed by the terrible smell of the dead bodies. So they covered the bodies with dust.”

Humanitarian crisis

Ethiopian federal troops first moved into Tigray in November with the stated aim of “restoring the rule of law” by deposing the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the regional ruling party.

vThe deployment followed attacks on army bases by fighters loyal to the TPLF, which has been feuding with the government of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed since shortly after he came to power, in 2018.

On November 4, 2020, Ethiopia’s federal government launched what it called a “law enforcement operation” against “rogue” leaders of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the region’s ruling party, after TPLF fighters attacked a federal military base. TPLF leaders called the federal government’s response a war against the people of Tigray.

But tensions between the central government and TPLF have been smoldering since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s appointment in April 2018 following a monthslong popular revolt.

He initiated a peace agreement with neighboring Eritrea and pushed for reforms such as opening trade, releasing political prisoners and unifying ethnic groups under his new Prosperity Party — measures that also sapped power from the long-dominant TPLF. Reforms that opened up political and economic space also have fueled inter-ethnic violence across the country, with more than 1.2 million people displaced by conflict in 2020 even before the Tigray crisis, the International Organization on Migration reports.Visit these sites for more about the Ethiopian refugee crisis:

The fighting in Tigray in its first month alone is believed to have claimed thousands of lives and displaced more than 1 million people. At least 50,000 have fled to neighboring Sudan, the U.N.’s refugee agency says. Ethiopia itself hosts more than 1 million refugees from other countries.

VOA journalists are reporting on the crisis for TV, radio and digital media. Covering the plight of refugees and displaced people around the world is one of VOA’s top priorities, as part of its mission to inform, engage and connect people in support of freedom and democracy.

ETHIOPIAN REFUGEES FLEE TO SUDAN

THE DIVISION OF ETHIOPIA’S MAJOR ETHNICITIES

South African Liberal Dream & Nightmare Reality – July 14th 2021

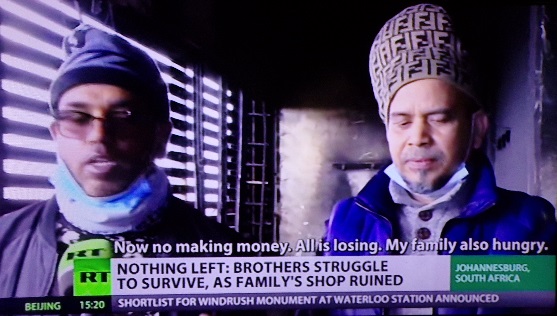

The death toll from rioting in South Africa rose to 72 on Tuesday, AFP reported, including 10 people trampled to death during looting at a mall, as police and the military fired stun grenades and rubber bullets to try to halt the unrest set off by the imprisonment last week of former President Jacob Zuma.

Hundreds have been arrested in the lawlessness that has raged in poor areas of two provinces, where a community radio station was ransacked and forced off the air Tuesday and some COVID-19 vaccination centers were closed, disrupting urgently needed inoculations.

Many of the deaths in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces occurred in chaotic stampedes as thousands of people stole food, electric appliances, liquor and clothing from stores, officials said.

“We are confident our law enforcement agencies are able to do their job successfully. The current situation on the ground is under strong surveillance and we will ensure it will not deteriorate further,” the police minister Bheki Cele told reporters, saying the disturbances risked severe shortages of medicines and foodstuffs across South Africa.

Zuma jailed: Arrests as protests spread in South Africa – July 11th 2021

Dozens of people have been arrested in South Africa as violence spreads following the jailing of former president Jacob Zuma.

Pro-Zuma protesters first took to the streets after the 79-year-old handed himself to authorities on Wednesday to begin a 15-month sentence.

But police now say criminals are taking advantage of the chaos, which spread from his home province of KwaZulu-Natal to Johannesburg, in Gauteng.

NatJOINTS, the national intelligence body, said some 300 people had barricaded a major highway in Johannesburg – South Africa’s economic hub.

About 800 people were also involved in an incident in which one police officer was shot in Alexandra, a township in Johannesburg. Two other officers were hurt.

Police also responded to reports of looting in both Johannesburg and KwaZulu-Natal. More than 60 people have been arrested so far.

It is unclear if they are linked to the pro-Zuma protests, with KwaZulu-Natal police spokesman Jay Naicker telling news agency Reuters officers had seen “criminals or opportunistic individuals trying to enrich themselves during this period”.

Researchers uncover Africans’ part in slavery

October 20, 1995

Web posted at: 8:25 p.m. EDT

Posted July 2nd 2021

From Correspondent Gary Strieker

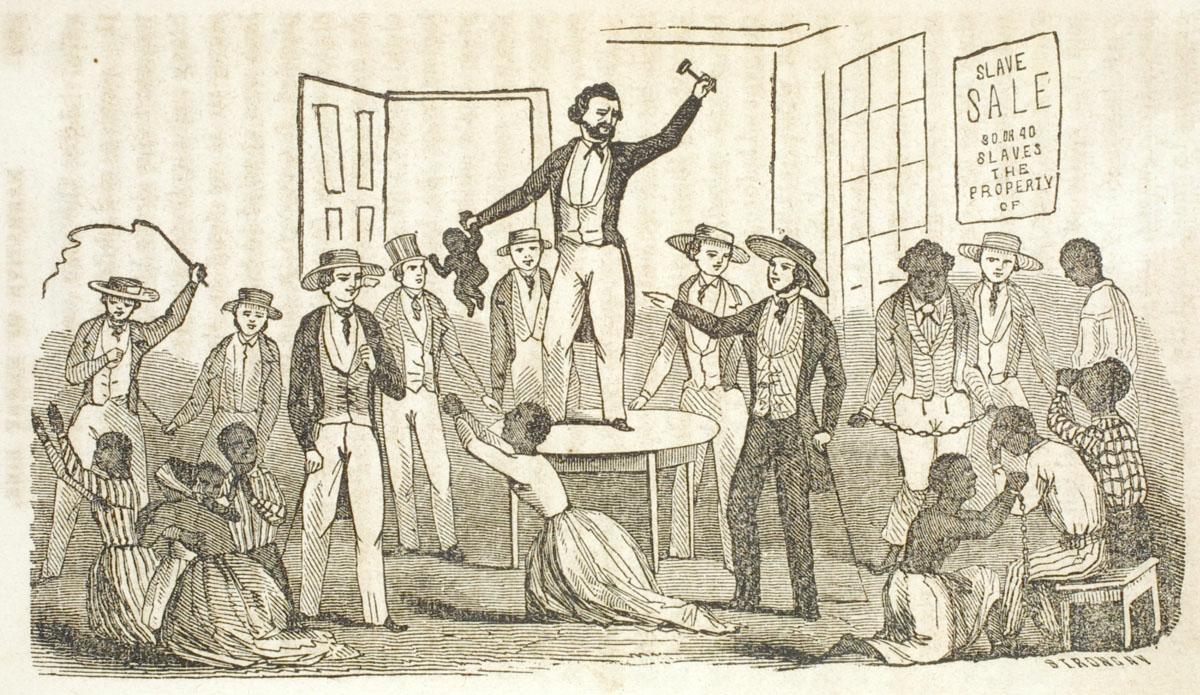

CAPE COAST, Ghana (CNN) — For centuries along the West African coast, millions of Africans were sold into slavery and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas.

The middlemen were European slave traders based in forts like Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle, now a tourist attraction and a somber reminder of a brutal crime against humanity.

That crime is usually blamed entirely on the European outsiders who inflicted slavery on African victims. But new research by some African scholars supports a different view – – that Africans should share the blame for slavery.

“It was the Africans themselves who were enslaving their fellow Africans, sending them to the coast to be shipped outside,” says researcher Akosua Perbi of the University of Ghana. (88K AIFF sound file or 88K WAV sound)

Based on her studies, Perbi says that European slave traders, almost without exception, did not themselves capture slaves. They bought them from other Africans, usually kings or chiefs or wealthy merchants.

The question is, why did Africans sell their own people?

For a thousand years before Europeans arrived in Africa, slaves were commonly sold and taken by caravans north across the Sahara.

“Slavery did exist in Africa,” says Irene Odotei of the University of Ghana.

In many African cultures, slavery was an accepted domestic practice, but it was slavery of a different kind. In Africa, the slave usually had rights, protection under law, and social mobility.

“Many house owners would call their slaves as their daughters or sons,” says Perbi. “They became part of the kin or family or lineage of the owners.” (100K AIFF sound file or 100K WAV sound)

The Atlantic slave trade grew at a time when many African states were at war with each other, taking prisoners that could easily be sold to traders in exchange for guns.

“It’s the gun which was a deciding factor in the slave trade — introduced by Europe,” says Odotei.

But while Africans may have sold their own people into slavery, researchers say the kings and chiefs had no idea of the brutality of slavery on the other side of the ocean. If they had, they say, maybe the slave trade across the Atlantic would never have grown so huge, or lasted for so many years.

Sharing the guilt for slavery may be disturbing and painful for Africans, but researchers say their objective is clear.

“They’re trying to uncover the facts so that people will take a lesson from the evil of the past and say ‘no more,'” says Kwame Arhin of the Institute of African Affairs.

And there is one thing they insist they are not doing.

“I’m not trying to shift blame or to make the Europeans feel less guilty,” explains Perbi.

For what many believe was the world’s greatest crime against humanity, there is more than enough guilt to share.

Related sites

African Wealth & Health – July 2nd 2021

Eswatini – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swaziland

Eswatini , officially the Kingdom of Eswatini (Swazi: Umbuso weSwatini), sometimes written in English as eSwatini, and formerly and still commonly known in English as Swaziland (/ˈswɑːzilænd/ SWAH-zee-land; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its north, west, and south. At no more than 200 kilometres (12…

- History

- Geography

- Government and politics

- Economy

- Society

- Culture

- See also

Artifacts indicating human activity dating back to the early Stone Age, around 200,000 years ago, have been found in Eswatini. Prehistoric rock art paintings dating from as far back as c. 27,000 years ago, to as recent as the 19th century, can be found in various places around the country. Wikipedia · Text under CC-BY-SA license

Images of Swaziland

bing.com/imagesBeautyPeopleMapBeautifulCountryFoodVillagesTourismPrincessCityTodayLandscapeSouth AfricaDancePlacesFlagTribesMountainsNatureHouses

The Kingdom of Eswatini (Swaziland): Official Tourism Website

Eswatini Regions Eswatini Experiences Events Calendar Despite being the smallest landlocked country in the Southern hemisphere, and the second smallest country in continental Africa, Eswatini, formerly known as Swaziland, more than makes up for its lack of size with …

Swaziland – Country Profile – Nations Online Project

A virtual guide to Swaziland, the small landlocked kingdom in southern Africa is bordered by South Africa and Mozambique. The country covers an area of 17,364 km², it is one of Africa’s smallest countries, slightly larger than half the size of Belgium, or slightly smaller than the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Fools Paradise June 3rd 2021

The aid industry is riddled with parasites and corrupt officials while resources are squandered for the elites’ benefit and extravagant lifestyle and ‘respect.’ They don’t want whites lording it over them which is why they call any white men a threat in that way, They are labelled white supremacists before they start anything..

Young blacks don’t think beyond escaping into the white world of the west where they declaim against white supremacy because they want their share of an unsustainable lifestyle.

Their continent is riddled with war , along with dreadful consequences, , disease violent gang crime including rape and the west is getting that way. Meanwhile superficial idiots preach about the climate change and why we must follow lockdown rules when there is open door population movement for a whole lot of people who appear to have rights but not responsibilities. Our modern day Neros keep telling us that we must fight the far right , rather than face reality. That’s how we got two world wars. Robert Cook

Patronising Tory Caroline Nokes wants it all to be seen as men oppressing women and whites oppressing blacks. We mustn’t see the class exploitation , profiteering and overpopulation issues. So many views are now criminalised by the elite consensus. Robert Cook

Led by the former Tory cabinet minister and chief whip Andrew Mitchell, who has been rallying against the cuts, the rebel MPs said they were “confident” of having the numbers to overturn the prime minister’s healthy Commons majority.

The amendment signed by 18 MPs — including 14 Conservatives — boasts other senior figures such as former cabinet ministers David Davis and Jeremy Hunt, alongside the chair of the international development committee, Sarah Champion.

It comes amid intense criticism of the government’s decision last year to flout the Conservative general election manifesto pledge and move to slash overseas aid spending from 0.7 per cent of national income to 0.5 per cent.

Ministers have insisted the cut — estimated to be around £4 billion — is only a temporary measure due to the economic fallout of the Covid pandemic, but have refused to test support in a Commons vote, or outline any timeframe for the budget to be restored.

The risk of an embarrassing defeat for the government over its decision to cut aid for some of the poorest and unstable areas of the globe could come just days before the prime minister hosts leaders from the G7 nations, including US president Joe Biden.

Mr Mitchell has tabled an amendment to the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria) Bill, a piece of legislation which establishes a new “high-risk, high-reward” research agency backed with £800 million of taxpayers’ cash to explore new ideas.

The explanatory note of the amendment says: “This new clause is intended to reaffirm the duty in the International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act 2015 for UK official development assistance (ODA) to amount to 0.7 per cent of gross national income each year. It will require Aria to make up any shortfall in that proportion from January 2022”.

It will be up to speaker Sir Lindsay Hoyle to decide whether the amendment is selected for consideration when the Bill returns to the Commons for further consideration on 7 June.

Tobias Ellwood — the Conservative chair of the Commons Defence Committee who has signed the amendment — described the government’s cut as “devastating” on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

Asked about the size of the rebellion, he said: “We need the number 45 [to defeat gov] and at the moment I’m confident – quietly, cautiously confident – that we’re going to get that number”. So I do hope the government will recognise where we want to go and why we want to do this.”

“Next week at the G7 summit, members will address the simple question: is our world becoming more dangerous, or less?” he said.

“With growing authoritarianism, extremism extending beyond the Middle East, climate change creating a raft of new challenges, and of course so many countries holding out for help to tackle the pandemic, I think the answer is pretty clear indeed”.

He added: “And yet here were are holding this summit to address these very issues, but choosing to cut the aid budget — the one G7 nation to do so. As a leading western nation would must remain an exemplar in helping shape the world around us. Retaining that aid budget is absolutely in the spirit of Global Britain.”

Opposition parties, including Labour and the Liberal Democrats, have severely criticised the cut in funding for overseas aid and are almost certain to back the amendment, if it is selected next week.

Lisa Nandy, the shadow foreign secretary, told The Independent: “As the eyes of the world turn to Britain ahead of next week’s G7 Summit in Cornwall, the government faces defeat over its short-sighted and self-defeating decision to cut foreign aid. At the very moment our international partners are stepping up to lead the global response to the pandemic, the Tories are in retreat.

“Parliament is ready to do the right thing and vote to reverse these ill-judged cuts – will the government do the same?”

Caroline Nokes — another former Tory minister backing the amendment — told ITV’s Peston programme: “It’s taken quite a lot of manoeuvring to find an opportunity to actually have a vote on this. I feel really strongly that we legislated for the 0.7 per cent commitment and the cuts are affecting women and girls.

“I am chair of the Women and Equalities Select Committee, the cuts of 85 per cent to family planning, the cuts to girls’ education – what we know from that is that if girls are not educated they won’t be empowered, they won’t be empowered if they are pregnant too early.

“Women will die because of these cuts to family planning so I have joined forces with colleagues to make sure we can have a vote on it and I will be voting to keep that 0.7 per cent.”

Comment The very last purpose foreign aid has ever served is defeat poverty, The comment from Caroline Nokes is typical of the white upper middle class feminists in politics. They are fixated with the concept of female empowerment as the solution to the all the world’s problems.

History is being re written. The West’s white working class slaves are far less valuable. They are not allowed a racial identity. To claim one is to be racists against balcks. All blacks are seen as victims . They are portrayed as equally downtrodden. The left wing liberal view is that the nice black people were living in harmony with each other and nature, when the nasty white people arrived to take them away to the Americas for work as slaves..

The reality was very different . Black dynasties grew richer and more powerful off the sale of fellow blacks. The liberals and BLM don’t want to talk about this.

The problem is that the British and other European imperialists left behind ruthless dictators who shared exploitation of vast resources with big business interests. Their black masses were left to religion and to poverty, consequent overpopulation encouraged by religious delusion and hopes for a wonderful afterlife.

The only afterlife young black Africans can hope for is escape to the western industrial world. Some fans of foreign aid see cutting it as making the flow of migrants and so called asylum seekers greater. The European elite condemn all arguments against them. The aid industry is headed up by people on six figure salaries. The aid industry is not about progressing the poor. It is about guaranteeing the profits of global elites and their corporations.

We will hear some impressive moralising from Britain’s political elite in the House of Commons today. They will say fine words and virtue signal, with no mention of the ugly truth. Tribal hierarchies and in fighting opened the door to the slave trade. It is very much the same today.

Talking about the past is a very clever diversion for the ignorant black masses to rise up against and ultimately for poor whites to rebel against.. The elite do not care. The symbolic removal of slave statues is cover for the new and ongoing slavery. This argument about a tiny cut in foreign aid is more diversion.

Foreign aid is like urinating money into a bucket with a hole in the bottom , connected to a pipe leading to the rich dictator’s home. Senegal recently bought their leader a new state of the art Airbus because the old one had been left idle and wouldn’t work. That is a metaphor for African leaders. Robert Cook

Meet PM Reigns, Ghana plus size dancer who airline prevent from travelling sake of her size May 28th 2021

Ghanaian plus size dancer, Precious Mensah dey call for reforms which go make de life of plus size people comfortable.

Popularly known as PM Reigns, de Di Asa dance competition winner reveal how society dey make provision for just slim people while neglecting plus size people.

She recount give BBC Pidgin Favour Nunoo how in 2019 she no fit travel to Dubai sake of her size.

“I be that type who dey like travel den experience de world, but unfortunately my first travel experience no happen sake of my size” Miss Mensah talk.

She add say “I pass through so many things… People go see you in town de say you be too fat, we fit get your brazier and pants or you dey sew dem?”

One time dem try kick am off public transport sake of dem try charge her fare for two people wey she disagree.

Miss Mensah talk about how plus size people dey like socialize den have fun but restaurants, cinemas den stuff no dey make provision for dem.

She call on event Organisers, restaurants, cinemas to make available free chairs wey no get arm so say plus size people fit patronize dem.

Africa is theirs – May 18th 2021

Ethiopia Chaos & Bloodshed Will Spread March 20th 2021

Inter-ethnic violence in Metekel predates a brutal three-month-old conflict further north that is pitting Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed against the former ruling party of Tigray.

The bloodshed has intensified just as the military is trying to assert control over Tigray, highlighting how Abiy, the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize winner, does not have the luxury of addressing just one security crisis at a time.

In mid-November, 34 civilians were killed in Metekel when gunmen attacked a bus.

In late December, one day after Abiy visited the area, more than 200 people perished in a pre-dawn massacre, some burned alive as they slept.

And last month more than 80 died in a raid involving knives and arrows.

Even as analysts puzzle over who and what is driving the violence, there are fears it could soon escalate.

Abiy’s government has unveiled plans to form a militia of civilians displaced by past attacks to return to Metekel to “protect” those remaining.

At a displacement camp in the town of Chagni, east of Metekel, Girmay is one of many residents who back this move.

“I don’t fully support the idea of forming a militia, because in my opinion it’s like saying, ‘Kill one another,'” Girmay told AFP as he clutched a wooden cross.

“But if there are no other options and if (the gunmen) are not disarmed, we shall train some recruits from here to protect our lives.”

On the night before Orthodox Christmas last month, Ethiopian priest Girmay Getahun donned a white robe and, Bible in hand, walked down the dirt road to his church to prepare for services.

Around midnight, heavily-armed fighters arrived in his village, in Ethiopia’s western Benishangul-Gumuz region, sending Girmay fleeing into the forest to hide for two days.

He returned to a horrifying sight: the corpses of his eight housemates, all day-labourers on teff and peanut farms, who had become the latest victims in a gruesome, perplexing string of attacks.

Hundreds have died and tens of thousands have fled their homes.

Inter-ethnic violence in this lowland area, known as Metekel, predates a brutal three-month-old conflict farther north that has pitted Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed against the former ruling party of the Tigray region.

Comment A small black elite makes a fortune from their dictatorships, in cahoots with western billionaires and muti national corporations. White working classes take the blame for the black and white elite who worked together trading slaves. These whites feel the pressure of the inevitable black and Muslim population into their countries and neighbourhoods , with elite slogans telling them about a wonderful multiculture that will never bother that elite. It’s a neat trick, but the media and police serve them. R.J Cook

LGBT+ History Month: Eudy Simelane – the international footballer murdered for being gay

By Keely WatsonBBC Sport

Last updated on

12 February 202112 February 2021.From the section Football

Warning: This article includes references to sexual assault and violent crime.

An international footballer, coach and aspiring referee, Eudy Simelane dedicated her life to the sport.

She was one of the first openly gay women to live in her township of Kwa-Thema in South Africa and was a well-known LGBT+ activist.

But because of her sexuality, Simelane was brutally raped and murdered in 2008, aged just 31.

This is the story of her life and how the legacy of her death is still impacting South African society.

‘She was a diamond’

Simelane was born on 11 March 1977, in Kwa-Thema, a township in the Gauteng province, south east of Johannesburg.

Her interest in football started when she was only four years old, demanding her brother Bafana always took her to practice with him despite it not being a sport commonly played by women at the time.

Passion soon became dedication as she honed her skills daily.

“Five o’clock in the morning, she [would be] at the gym – football was her favourite and her priority”, her late mother Mally recalled at a memorial lecture in 2016.

Nicknamed ‘Styles’ because she was left-footed, midfielder Simelane joined her local team, Kwa-Thema Ladies, now known as the Springs Home Sweepers.

Speaking to the BBC World Service in 2018 about Simelane’s popularity on the pitch, her father Khotso said: “Everyone came to the ground when she played, number six”.

Springs Home Sweepers has produced a number of stars including Janine van Wyk, South Africa’s most capped footballer and captain of the national team, known as ‘Banyana Banyana’, meaning ‘the girls’.

Simelane played several times for the national side, coached four local youth teams and wanted to qualify to become her country’s first female referee.

A campaigner for equality rights and social change, she was one of the first women to come out as a lesbian in South Africa

.

In the 2020 Eudy Simelane Memorial Lecture

, her brother, Bafana said: “In sport she was a diamond, scoring beautiful goals. She was a marvellous person, intelligent, everything. It was a package. Everything you would find in Eudy. Jokingly she was playing, teasing others. That is what I miss about her.”

On 27 April 2008, Simelane’s body was found in a stream just a few hundred metres from her home in Kwa-Thema.

Reports stated she was approached after leaving a pub, raped and then stabbed repeatedly.

Despite her death shocking many, activists claimed many lesbians in South Africa were targeted for ‘corrective rape’, a crime where the perpetrator aims to ‘cure’ the victim of their sexuality, converting them to heterosexuality.

pleaded guilty to the rape and murder of Simelane in February 2009 and was sentenced to 32 years in prison. The following September, Themba Mvubu was also found guilty of the crimes and was sentenced to life in prison. When questioned by reporters in court, he responded: “I’m not sorry.”

‘It opened the eyes of many’

Simelane’s sexuality put her in a vulnerable position, something her mother recognised, telling the BBC, “the whole of South Africa knew Eudy was a lesbian”.

The unfortunate reality is Simelane’s story isn’t unique – she is one of many victims of similar, horrific crimes in South Africa.

A year prior to her death, Sizakele Sigasa