https://www.waterstones.com/author/robert-cook/435753/page/1

https://www.bookbub.com/hero-books-discounted-ebooks/2?source=pocket_uk_yellow_past_deals_theme_3

June 17th 2024

| Q&A How Suzanne Scanlon Recovered In her new book, Committed, Suzanne Scanlon writes about being institutionalized in her youth and how she eventually got out. |

| It’s almost unimaginable now that Suzanne Scanlon, an English professor in Chicago and the author of two novels, spent three years of her early 20s in a state mental institution. As a Barnard student, she attempted suicide, suffering from a depression that stemmed from her unresolved grief over her mother’s death when Scanlon was only 8 years old. But instead of being treated and released, she was transferred from the care of one incompetent doctor to another for years, given shifting diagnoses and experimental drug treatments, and locked away from the world for so long that reentering it began to seem impossible. |

| Yet, as Scanlon writes in her new memoir, Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen, the experience was in some ways perversely, almost inadvertently, helpful. “In the hospital I took it for granted, the idea that we somehow needed to get worse,” she says. “They would break us apart and then put us back together again.” This process of breaking apart shaped Scanlon’s life and worldview irreparably. In her novels, Promising Young Women and Her 37th Year: An Index, Scanlon uses the same material she would mine in her memoir, but this book reads very differently — seamlessly interweaving the writing of other writers and thinkers in a conversational way, sort of as if Maggie Nelson didn’t write like an academic. Scanlon says she sees the novels and the memoir as one ongoing book with a story that changes as she gets older and can see things from a distance. The result is a deep, sometimes harrowing book about loss, grief, and the way literary representations of mental illness shaped Scanlon’s experience of her own life. |

June 15th 2024

People often overestimate their resilience following failure, research suggests

Exaggerating the likelihood of success after failure may make us less willing to help others who are struggling.

It’s wrongly assumed that people focus on their mistakes and learn from them after failure. Kannika Paison / Getty Images

June 10, 2024, 10:27 PM GMT+1

By Shiv Sudhakar, M.D.

The myth that failure is always a good teacher may need an update.

People tend to overestimate the likelihood of success following failure, which may make us less willing to help others who are struggling, according to a new study.

A team of researchers from the business schools of Northwestern, Cornell, Yale and Columbia universities analyzed data from different online surveys including over 1,800 adults in the United States mostly between the ages of 29 to 49. One survey involved oncology nurses attending a virtual conference.

“We wanted to see if people think about resilience wrong,”lead author Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, assistant professor of management and organizations at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, told NBC News in an email.

The study was published online Monday by the American Psychological Association in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

The researchers looked at how people predicted the resilience of professionals such as lawyers, teachers and nurses, as well as people with substance use disorders and heart problems.

“People thought that tens of thousands of professionals who failed standardized tests would go on to pass (who don’t), that tens of thousands of people with drug addiction would get sober (who don’t), and that tens of thousands of individuals with heart failure would make major lifestyle changes to improve their health,” Eskreis-Winkler wrote.

When people believe that others who have experienced setbacks will grow from their failure on their own, they are less motivated to help those in need because they believe these problems will “self-correct,” the report said.

The researchers also found that participants wrongly assumed people focus on their mistakes and learn from them after failure.

In one of the findings, people who exaggerated the benefits of failure were less interested in channeling taxpayer dollars to support people with drug addiction and formerly incarcerated people.

However, when the researchers corrected exaggerated beliefs about the benefits of failure, the same participants increased their motivation to help.

“The main finding is that people systematically — blissfully — overestimate the likelihood of resilience following failure,” according to the researchers.

This “pollyannish” perception allows people to take more chances despite erroneously believing that failure fuels success, Eskreis-Winkler said in the email. “But from a helping perspective, exaggerating the benefits of failure is disastrous.”

Recommended

Abortion RightsAbortion pill access could still face challenges after Supreme Court decision

Abortion RightsWhat to know about mifepristone access after the Supreme Court ruling

In reality, it’s difficult to learn from a bad experience because failure is “demotivating and ego-threatening,” the report found.

The findings highlight how our outside perspective tends to focus on what can be learned from a failure, overlooking that people living through a setback may not perceive it as a learning opportunity.

It’s a painful ego lesson, said Dr. Ryan Sultan, director of the Mental Health Informatics Lab at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

“If you have failed at something, just retrying is likely not sufficient to change your outcome,” Sultan said.

Sultan recommends re-evaluating the situation by asking:

- What new strategies could be adopted?

- What resources or support systems could we engage with that would improve our chances of success in the future?

Dr. Lama Bazzi, a psychiatrist in private practice in New York City, advocates patience, despite the desire to quickly move forward. Achieving a goal often means tolerating the discomfort of failing in order to “grow” as a person.

“In order to change course, you must feel uncomfortable, analyze where you went wrong, and make a conscious effort to approach similar future challenges mindfully and differently,” said Bazzi, who was not part of the study.

The study findings don’t mean that if you fail at something, you can’t ever succeed.

People need to be mindful of the path that led to these outcomes and re-evaluate it with a critical eye, Sultan noted.

“As my father, who is also a psychiatrist, told me in my youth: When you fail, Ryan, you must ask yourself the hard questions of what you did to contribute to that failure so you can grow and learn from that experience,” Sultan said.

Although the researchers analyzed different populations in the U.S., including students, professionals and medical patients, more research is needed to generalize the study’s findings to non-Western cultures, which have different perceptions, interpretations and reactions to failure, the study said.

June 8th 2024

1984: How did the Isle of Jura help shape Orwell’s masterpiece?

Craig Williams and Chris Diamond

BBC Scotland News

- Published7 June 2024

- Updated 9 hours ago

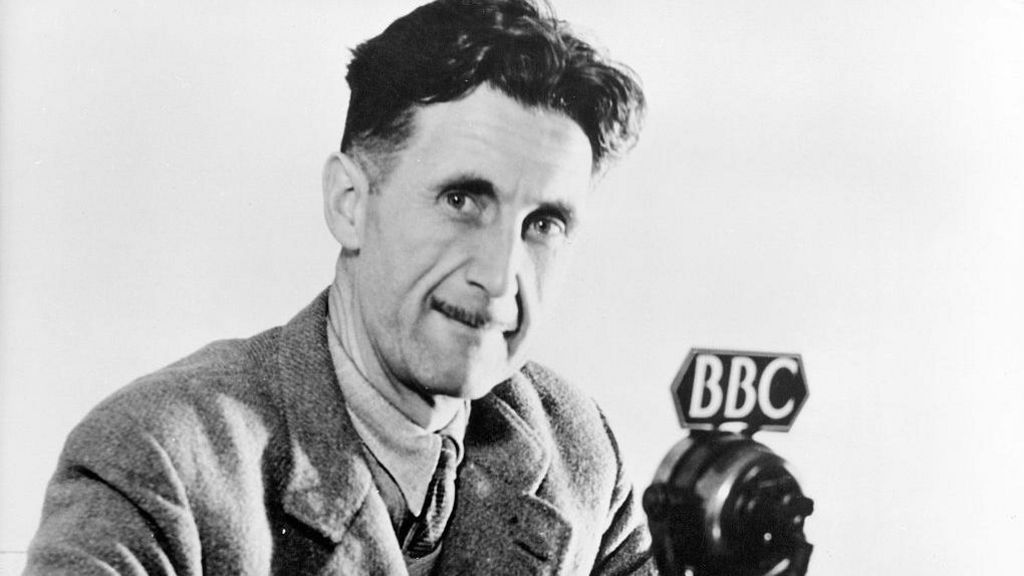

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four was published 75 years ago on Saturday.

It is the story of Winston Smith, an obedient citizen in an oppressive future state who slowly rebels against the system.

The book is a powerful study of totalitarianism and its effect on the individual.

It takes place in a future world of war, poverty, rationing and absolute state control.

Every action, word and even thought is monitored and controlled by the leader, ‘Big Brother’, and ‘The Party’.

It was written in a world ripped apart by fascism and against the backdrop of the early days of the Cold War and the spread of communism.

The novel is set in a London re-imagined as ‘Airstrip One’, the capital of ‘Oceania’. It is a rainy, filthy city, crumbling and battered, and almost entirely devoid of colour, warmth or comfort.

But it was written in an isolated and beautiful corner of the Isle of Jura as the author, afflicted by the tuberculosis which would soon kill him, sought to escape the noise, smog and damp of London, and get his warning to the world completed before he ran out of time.

Richard Blair turned 80 in May. A retired businessman, he has spent the past few decades minding the legacy of his father, Eric Arthur Blair – known to readers the world over as George Orwell.

Richard was adopted by Orwell and his first wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy just weeks after he was born in 1944.

His new mother died little less than a year later, leaving father and infant son alone together.

In the years following the end of the war in 1945, Orwell – finally well-off from the success of his novel Animal Farm after years of poverty – looked after Richard with the help of his family and a housekeeper.

But after a visit to Jura in September 1945, he began planning to move there.

He returned to the island repeatedly over the coming two years, bringing with him his extended family including his sister Avril and her partner.

He finally fulfilled his wish to decamp to the island full time in April 1947.

The house they rented, Barnhill, sits in the north of the island. It was barely habitable. Shabby, damp, cold and alone at the end of more than four miles of single track path.

Yet Richard has nothing but happy memories of his time there. His father was pleased with the move, too.

“It was a nice house. A bit rough and ready, but for him it was a lovely place to go to. Remote, certainly. It was, as he described it to friends, a ‘most un-get-at-able place,'” he says.

Richard credits his aunt with making the place habitable.

“Without her it would have been very difficult for my father to have survived properly. She was very practical and a good home-maker. So she got the house comfortable. As warm as one could expect it to be made.”

Much has been made of the often harsh Hebridean climate and whether Jura was the best place for a man suffering from tuberculosis.

It has even been suggested that living there in such spartan circumstances may have contributed to the grim tone of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Journalist Alex Massie, who is a regular visitor to the island, is sceptical.

“Orwell’s decision to live in the Hebrides – a long, long way away from London at a time when he was suffering from poor health – has created this vision of the sort of doomed novelist writing himself to death at the end of the world,” he says.

“That is a very romantic vision obviously, but it’s not one that bears very much scrutiny. In certain respects Jura was a healthier place to live than London. And so it was not some sort of mad or suicidal sojourn.

“It happened to be Jura that he went to, but almost anywhere that was isolated and rural would have sufficed because what he wanted was peace.”

Barnhill became home to Orwell and his family in 1947

That certainly corresponds with Richard’s memories.

“I loved it. It’s a wonderful island and for a kid it was just total freedom. Unlike London, on Jura you could just open the back door and off you went. There were thousands of acres of land you could walk over,” he says.

While the young Richard was enjoying the scenery and freedom, his writer father was avoiding the typewriter by working the land.

“He had by this time managed to try to get the garden dug over and planted. So that gave him a break from writing Nineteen Eighty-Four, which he had just started.

“Once he had established the garden, so he was growing vegetables, that was obviously of paramount importance for food. Because obviously it was the days of rationing and getting food was really difficult.

“We actually had a very good lifestyle. We had access to fish, to lobsters, to crabs. We had access to meat in the form of rabbits and lumps of venison that came from the estate from time to time.

“From that point of view we lived extremely well, if simply,” he says.

Orwell continued writing, though his health was deteriorating. At the end of 1947 he was hospitalised at the sanatorium in Hairmyres Hospital, then in the countryside outside Glasgow, but now in the new town East Kilbride.

When he returned to Jura in the summer of 1948 he was only just well enough to work on the book for which he would become most celebrated.

He completed it just before Christmas and the Blair clan left Barnhill for the final time in January 1949. Nineteen Eighty-Four was published five months later.

The following January, Orwell died after an artery burst in his lungs. He was 46.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a book whose reputation has grown and grown. Controversial from the moment it was published, it was unpopular with many on the left who were unhappy with what they saw as an attack on communism.

But it sold and kept selling. An acclaimed BBC production in 1954 brought it to a wider audience, and it gradually made its way onto college and school courses around the world.

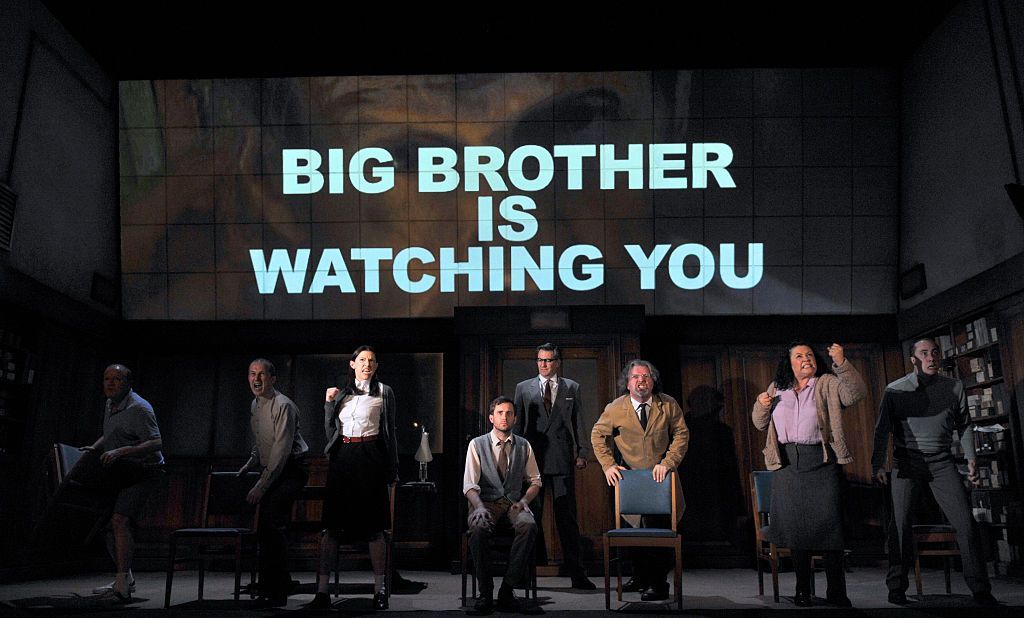

It has now sold more than 8 million copies, been adapted many times for stage and screen, and, in what can be seen as the ultimate measure of its power, was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988.

But as the book reaches its 75th anniversary, its greatest influence may be in how it changed the way we speak and think. In that way, it has come to mirror the very themes the book explores.

“Big Brother”, “Groupthink”, “Thought Police”, “Thought Crime”, “Room 101”, even the description “Orwellian”.

The book has left us with a rich legacy of words and ideas to describe the power of the state, totalitarianism, the role of technology and what it is to live in a surveillance culture.

For writer and film critic Hannah McGill, much of its power comes from its predictions.

“Sometimes I do think you get a sort of miracle of prescience with a certain piece of work, where it happens to hone in on a few ideas that prove to just really predict the preoccupations of the coming age,” she says.

“One thing that the book predicted correctly is that we now live in a society far, far more dominated by technology in ways that Orwell could not imagine, because nobody could.

“You only have to look at the role of the telescreen in Nineteen Eighty-Four and the fact that you now have this medium which is entertainment, propaganda, advertising and surveillance all at the same time.”

For Alex Massie, the book’s influence goes way beyond its success as an imaginative work.

He says: “It’s a book that many people think they know a lot about even if they haven’t actually read it and that’s quite unusual.

“And what makes Nineteen Eighty-Four quite distinct and a monumental achievement in certain ways is that you can have strong views about it without having read it.”

For Richard, his father’s greatest work remains prescient for the warnings it gives us about the world we continue to live in. For him, it remains relevant in the age of spin and modern technology.

“Any sort of situation where you are being fed disinformation, which can come from either left or right, which can come from whatever organisation wants to put it out there.

“They want to guide you down the path they want to take you. And I would suggest that is what has become ‘Orwellian'”.

Comment This reviived interest in Orwell and 1984 is more about slagging of Putin’s Russia. We are not supposed to notice that the U.S, U.K and EU Alliance is the totalitarian state which is working to gobble up the Baltic States, Black Sea, Russia and China to complete their tyranny.

R J Cook

May 31st 2024

05-25-2024WORK LIFE

Why your company should embrace the four-day workweek

At Fast Company’s Most Innovative Companies Summit, these execs from 4 Day Week Global, Kickstarter, and Public Policy Lab made a solid case for the four-day workweek.

From left: Tarveen Forrester, VP of People, Kickstarter; Shanti Mathew, Managing Director, Public Policy Lab; and Dale Whelehan, CEO, 4 Day Week Global [Photo: Celine Grouard for Fast Company]

The push for a four-day workweek has recently surged in popularity, spearheaded by Sen. Bernie Sanders’ proposed legislation. While the idea of a 32-hour workweek remains a fanciful notion for many, the idea is catching on with companies either fully hopping onboard or at least opting for a trial run.

Last week, Fast Company‘s Most Innovative Companies Summit brought together Dale Whelehan, CEO of 4 Day Week Global; Tarveen Forrester, VP of people at Kickstarter; and Shanti Mathew, managing director of Public Policy Lab to discuss the benefits of a shortened work week and how best to embrace it.

Reducing burnout to maximize productivity

Unsurprisingly, one of the main concerns of the four-day workweek is the effect it has on an organization’s productivity. Yet Whelehan argued the four-day workweek is ultimately a productivity intervention. Giving workers more time off significantly reduces burnout and improves employee engagement and retention, thus increasing the level and quality of output for the organization

Whelehan cited the Yerkes-Dodson’s Law, which models the relationship between stress and task performance. “You’re trying to get to that level where people get the optimal level of stress in their work to produce output without tipping them over the edge and into burnout,” he said. “That’s what a four-day workweek achieves.”

As a behavioral scientist, Whelehan said it comes down to leaders within organizations realizing they have to create “a new form of management that is focused on the physiology and psychology of humans.” And what’s better for employees in this regard is ultimately better for business.

Invest in more effective management

The objective of the four-day workweek is for workers to produce the same level of output in 32 hours as they formerly did in 40 hours. This means employees will be expected to produce more output per hour than they formerly did, leading to a style of work that will feel fast-paced and intense. The key to consistently achieve this objective will be to invest in manager effectiveness.

“When you’re moving fast, you have to understand what’s going on with your colleagues, your teammates around you, and other business units,” Forrester said. “Any company that’s thinking about the four-day workweek should really be prepared to invest in manager effectiveness.”

Create a new structure that works for your company

Simply offering a Monday to Thursday, 9 am to 5 pm workweek fails to solve the most fundamental problem with the way work is structured today: It’s incompatibility with the demands of many people’s daily lives. The key is finding a model that best fits employees and the organization as a whole.

For example, in client-facing organizations, Whelehan suggested a staggered approach to staffing, e.g. having some employees work Monday to Thursday and some Tuesday to Friday. Or a company could simply hire more staff. Sure there are more costs associated with that approach but, as Whelehan explained, “when you look at the macroeconomic costs, significant reductions in burnout, resignations, the cost of recruitment, there’s a net economic benefit by creating what essentially is a much more sustainable human resource structure.”

Making time for creativity

The four-day workweek most importantly frees up more time for employees. Increased leisure time not only increases wellbeing, but has historically been important in facilitating the creativity that leads to human progress.

“People are so multifaceted and we’re living in a world where we’re so overstimulated,” Forrester said. “And so when you’re giving people time back, you’re giving them the agency to have a life and have experiences outside of work.”

“That comes back to us tenfold and is able to fuel the organization,” she continued, “because when you have experience as outside of work, it drives things like your curiosity. It drives things like ideation. It drives things like your connectedness to self.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.

Work Smarter, not harder. Get our editors’ tips and stories delivered weekly.

May 30th 2024

I didn’t start pension saving until age 35. Here’s what to do if you didn’t either

Jessie Hewitson would love to spend retirement in a villa somewhere abroad – and is making up for lost time with her pension saving to achieve this

May 27, 2024 12:00 pm(Updated May 28, 2024 10:22 am)

Many people dream of spending time abroad when retired. But how to afford it?

I have a plan for my retirement. It’s to spend three months a year in a villa somewhere abroad – Spain, Italy, Greece – and write books. Or maybe I’ll sod the writing and just read books and spend lots of time by palm trees.

Either way I plan to be abroad for a reasonable chunk of my retirement. Of course the issue is paying for this.

If you are feeling too happy and need an immediate downer, I recommend logging on to your pension website and clicking on the pension modeller tool. I do it from time to time and it’s savage.

https://buy.tinypass.com/checkout/template/cacheableShow?aid=Xi7fMnt7pu&templateId=OTDEKJMG2GFZ&templateVariantId=OTVNF73P1FGOB&offerId=fakeOfferId&experienceId=EX94U7VN8UTD&iframeId=offer_b1e946a144edbc72415a-0&displayMode=inline&pianoIdUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fid.tinypass.com%2Fid%2F&widget=template&url=https%3A%2F%2Finews.co.uk

Read Next

‘We’ll be paying it off well into our retirement’: The rise of marathon mortgages

The modeller shows you how little your pension savings, which in every other context would be an enormous amount of money, will equate to a year when you retire (though it assumes you retire at the state pension age and you put your money in an annuity, rather than the far more common arrangement of draw-down).

Part of the reason I want to cry when I look at the modeller is I am a tricky age for retirement saving. Auto enrolment came in when I was in my mid 30s, so while my generation benefited from its introduction it would have been better had it happened 10 years earlier. Especially as financial security, in the form of defined benefit pensions, was getting scarcer and annuity rates have generally been low.

Millions of others like me therefore managed to get to our mid-30s without saving a penny for retirement (not to mention the self employed who don’t have auto enrolment). But then I moved into personal finance journalism, and auto enrolment began, and my bacon was saved.

But there is no room for complacency and I’m going to have to be very sensible, and a bit lucky too, if those cherry blossom trees in Japan are going to be witnessed first-hand.

So here is what I’ve done to make up for lost time, and what I think others in similar positions should consider doing.

- 1. Save more. I currently pay 16 per cent into my pension (my employer contributes 8 per cent, and so do I), but I have saved as much as 28 per cent when my mortgage was smaller. Saving this much isn’t easy to do but you just have to bite the bullet, up your contributions and then you get used to your new salary normal.

- 2. Make sure you get the highest employer contribution you can. Often, employers will contribute more to your pension, if you contribute more. Some may match your contributions for example. An extra 1 or 2 per cent can equate to ten of thousands of pounds more when you retire. In the past I have asked for higher employer contributions rather than a boost to salary in salary negotiations. I have found that companies can be happier to add more to your pension than they are to your salary – it’s a bit daft as it’s all costs the company money (and makes you more) but it probably moves on to someone else’s spreadsheet this way, so always worth a try.

- 3. Take control of your investing. Around 90 per cent of us have our money sitting in default pension funds (the one your company puts you in when you start saving), which typically have 70 per cent invested in equities and 30 per cent in bonds or cash. This is an approach designed not to scare the horses – you get growth but it’s meant to be steady. But I need the horses to be scared, at least a bit – if I’m going to make up lost ground – and I still have enough time for them to calm down again before I need the money. So I have all my money in equities.

- 4. Keep track of your pension. It takes about 15 minutes and I do it every six months or so. I remind myself what I’m invested in, look up the “fund factsheet” online (this will give you all the information about where the fund is invested in and what the returns are, ie how much money it is making you). In this factsheet you’ll see a graph tracking the fund’s performance against a benchmark in its sector – if it’s underperforming the benchmark for over a year or two it’s sensible to rethink if you want to keep your money there.

- 5. Consider treating different pensions differently. This doesn’t apply to me as I have all my pension money in one place – this keeps my pension admin down – but if you had more than one pension and you are worried about taking more risk, you could treat your pensions differently. Consider keeping one in the lower-risk default fund and take more (sensible) risk with your other pensions.

- 6. Consider saving as a couple, if you’re in one. If one of you is a basic-rate taxpayer and the other higher rate, then it’s sensible to put more money into the pension of the higher-rate taxpayer, particularly if they expect to be a basic-rate taxpayer in retirement. This way you get more tax relief when you put the money in and pay less when it comes out. But if you divorce make sure this is factored in as part of the financial settlement.

- 7. Stay engaged. Readers of my last column will know I’ve spent hours trying and failing to login to my Scottish Widows pension app. Well at last I managed – let the choirs sing – thanks to some help from the company’s IT department. I wanted to give up, but I didn’t, and now I check on my pension a couple of times a week, all the faff seems worth it. Hopefully it will mean I save more, and then when my career is over, I’ll have enough for a few more aperitivos at my villa in Tuscany.

May 29th 2024

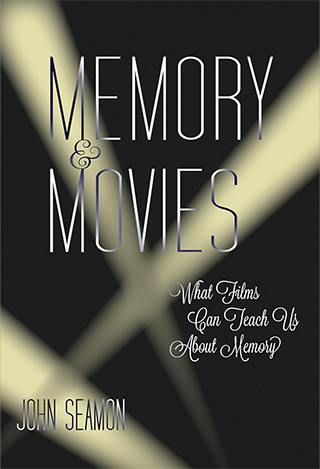

How Actors Remember Their Lines

In describing how they remember their lines, actors are telling us an important truth about memory.

By: John Seamon

After a recent theater performance, I remained in the audience as the actors assembled on stage to discuss the current play and the upcoming production that they were rehearsing. Because each actor had many lines to remember, my curiosity led me to ask a question they frequently hear: “How do you learn all of those lines?”

Actors face the demanding task of learning their lines with great precision, but they rarely do so by rote repetition. They did not, they said, sit down with a script and recite their lines until they knew them by heart. Repeating items over and over, called maintenance rehearsal, is not the most effective strategy for remembering. Instead, actors engage in elaborative rehearsal, focusing their attention on the meaning of the material and associating it with information they already know. Actors study the script, trying to understand their character and seeing how their lines relate to that character. In describing these elaborative processes, the actors assembled that evening offered sound advice for effective remembering.

Similarly, when psychologists Helga and Tony Noice surveyed actors on how they learn their lines, they found that actors search for meaning in the script, rather than memorizing lines. The actors imagine the character in each scene, adopt the character’s perspective, relate new material to the character’s background, and try to match the character’s mood. Script lines are carefully analyzed to understand the character’s motivation. This deep understanding of a script is achieved by actors asking goal-directed questions, such as “Am I angry with her when I say this?” Later, during a performance, this deep understanding provides the context for the lines to be recalled naturally, rather than recited from a memorized text. In his book “Acting in Film,” actor Michael Caine described this process well:

You must be able to stand there not thinking of that line. You take it off the other actor’s face. Otherwise, for your next line, you’re not listening and not free to respond naturally, to act spontaneously.

This same process of learning and remembering lines by deep understanding enabled a septuagenarian actor to recite all 10,565 lines of Milton’s epic poem, “Paradise Lost.” At the age of 58, John Basinger began studying this poem as a form of mental activity to accompany his physical activity at the gym, each time adding more lines to what he had already learned. Eight years later, he had committed the entire poem to memory, reciting it over three days. When I tested him at age 74, giving him randomly drawn couplets from the poem and asking him to recite the next ten lines, his recall was nearly flawless. Yet, he did not accomplish this feat through mindless repetition. In the course of studying the poem, he came to a deep understanding of Milton. Said Basinger:

During the incessant repetition of Milton’s words, I really began to listen to them, and every now and then as the poem began to take shape in my mind, an insight would come, an understanding, a delicious possibility.

In describing how they remember their lines, actors are telling us an important truth about memory — deep understanding promotes long-lasting memories.

A Memory Strategy for Everyone

Deep understanding involves focusing your attention on the underlying meaning of an item or event, and each of us can use this strategy to enhance everyday retention. In picking up an apple at the grocers, for example, you can look at its color and size, you can say its name, and you can think of its nutritional value and use in a favorite recipe. Focusing on these visual, acoustic, and conceptual aspects of the apple correspond to shallow, moderate, and deep levels of processing, and the depth of processing that is devoted to an item or event affects its memorability. Memory is typically enhanced when we engage in deep processing that provides meaning for an item or event, rather than shallow processing. Given a list of common nouns to read, people recall more words on a surprise memory test if they previously attended to the meaning of each word than if they focused on each word’s font or sound.

Deep, elaborative processing enhances understanding by relating something you are trying to learn to things you already known. Retention is enhanced because elaboration produces more meaningful associations than does shallow processing — links that can serve as potential cues for later remembering. For example, your ease of recalling the name of a specific dwarf in Walt Disney’s animated film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” depends on the cue and its associated meaning:

Try to recall the name of the dwarf that begins with the letter B.

People often have a hard time coming up with the correct name with this cue because many common names begin with the letter B and all of them are wrong. Try it again with a more meaningful cue:

Recall the name of the dwarf whose name is synonymous with shyness.

If you know the Disney film, this time the answer is easy. Meaningful associations help us remember, and elaborative processing produces more semantic associations than does shallow processing. This is why the meaningful cue produces the name Bashful.

John Seamon is Emeritus Professor of Psychology and Professor of Neuroscience and Behavior at Wesleyan University. He is the author of “Memory and Movies: What Films Can Teach Us About Memory,” from which this article is excerpted.

April 25th 2024

More from GQ

- Switching Lanes With St. Vincent

- My Life Cleanse: One Month Inside L.A.’s Cult of Betterness

- The Provocations of Chef Tunde Wey

“The secret to walking to the South Pole is to put one foot in front of the other, and to do this enough times,” writes Erling Kagge in his 2017 book Silence.

It’s these kind of simple, profound statements that make the Norwegian polar explorer’s writing so compelling. Because though a statement like that might sound obvious (of course you get to the South Pole by walking to it), when it comes from the first person to complete the Three Poles Challenge—Kagge walked to the North Pole in 1990, the South Pole in 1993, and the summit of Mount Everest (the “third pole”) in 1994—it packs a surprisingly motivational punch.

The effect of reading his newest book, Walking, is similar. It is, essentially, a defense of moving slowly and thoughtfully in an age obsessed with speed and convenience. And, sure, that take brings to mind old-man-yelling-at-a-cloud vibes, but Kagge’s insights are sharp enough to slowly chip away at your skepticism, like a pickaxe working a block of ice.

Ultimately, his point is not that walking is a nice, mind-clearing activity (though it certainly can be). It’s that removing all friction from your life, and replacing it with the seductive speed of convenience, has pernicious effects.

For one thing, when we rush or move quickly, we stop being present and forget what we experience. (“High speed is a menace to memory, because memory depends on time and spatial awareness,” he writes.) Secondly, there’s a political aspect to walking: When we don’t walk among our fellow citizens—when we have the privilege of only traveling privately—we can become coldly detached from the fabric of the community. (“What would happen if world leaders were forced to take daily walks among the people?” Kagge asks.) And, finally, taking a shortcut to what you want often leaves you disappointed because objects of our desire are less meaningful without the struggle to capture them. (How much less interesting might summiting Everest be if you could just take an elevator to the top?)

We asked Kagge what walking might do for those of us interested in being a little bit more present, productive, and peaceful, but maybe not that interested in walking to any of the three poles.

Why do you think it’s important to not rush so quickly from A to B?

I am 56 years old, and when you start to go to 60th, 70th, 80th birthdays, people talk about life being too short. That’s their favorite subject. When you’re walking, the slowness somehow expands time. Speed collapses time. So if you walk towards a mountain, you can see it getting closer. You can smell the smells. You hear things and see how everything is changing.

Take New York, for instance. People always believe they save time by taking a taxi. Let’s say you take a taxi and it takes 10 minutes when walking would take 20. Mathematically, you save 10 minutes. But in those 10 minutes in a taxi, you didn’t experience anything. If you walk in New York, nothing great is going to happen, necessarily, but something is going to happen. That makes those 20 minutes so much more rich than the 10 minutes in the taxi. So I’m not walking because I think it’s better than driving. I’m walking because life is getting a little bit richer than if you drive.

We live in a time of hyper-convenience now: the friction between wanting something and getting it is nonexistent.

It’s all available. There’s no reason to be anti-technology. Many good things come with technology, but it’s also making your life so much cheaper in so many senses. It’s very much about living through other people and forgetting yourself. This book’s about experiencing yourself. All this about walking—it’s not about turning your back to the world. It’s about opening up, seeing people, experiencing the Earth.

If you’re living in the city, what are some ways to cultivate that inward-looking behavior?

Sometimes when I’m stressed, I’ll walk up the stairs backwards. It gets rid of all the noise in your head.

Really?

Then I really have to focus on what I’m doing, and I’m not thinking about what just happened and what’s going to happen next up on the list. Thinking is very much about not being present in your own life. And when I walk backwards, I’m certainly present in my life. That’s something you try to do when nobody’s watching.

I get the impression that you think time is wasted when you get stuck in a monotonous routine.

That’s the easiest option in life: to do the same things every day. You get up in the morning, you eat your porridge, you take the metro to the office. And of course most people have to go to the office every day, so there has to be repetition. But I think it’s easy to become a slave to it. Everything you do is foreseeable. There are absolutely no surprises. I’m not advising anyone to make a revolution out of their lives. But there are so many small possibilities for living a richer life. You have to get out of those routines every now and then.

I think a big disadvantage to life today is it’s very much alike. And with little variation in life, life feels short. But if you get some variation in, life feels so much longer.

Are there ways you build that variation into your life?

You need to make your life more difficult than necessary. Throughout the day, you have to choose between the easiest option and more difficult options. And usually, of course, you always choose the easiest option. In my experience, that’s quite often a mistake. I look at my own life and the happiest I’ve been is when I have chose the most difficult options. That’s kind of the meaning of life: to feel your own potential. To do that, you have to get out of your comfort zone.

Speaking of getting out of your comfort zone… How many years passed between you deciding you wanted to go to the North Pole, and you completing that trip?

Two years of preparation. The reason I succeeded is not because I’m physically more fit than everybody else. It has to do with the fact that I was very good with my preparations. This Norwegian polar explorer, Roald Amundsen, was the first guy to the South Pole in 1911. He said something like, “Victory awaits the one who has everything in order. People call it good luck. While defeat always follows bad preparations and people call it bad luck.”

It’s absurd to try to walk to the North Pole. It’s not rational. It’s not a clever, smart thing to do. So then you decide, and, afterwards, you start to think: Is it actually possible? That took me two years of preparation to find out. But, you do all that preparation and then, when you eventually stand on top of Mount Everest—like I did a few years later—first you are super happy about the summit. But, maybe two minutes later, you ask yourself, “How in hell should I get down again?”

Every feeling has an end. That’s also true with bad feelings. That is a part of the beauty of life: Nothing lasts.

How do you train for a trek to the poles?

I’ve been doing cross-country skiing my whole life. But to get ready for the poles, I went up into the mountains, and dragged a sled with me, because you have to drag everything you need for the whole expedition. Since there’s no snow in Norway in the summertime, I usually dragged tractor tires after me like a sled with ski poles, sometimes on roller skis—the skis with wheels—up the hills of Oslo. Of course, when you do something like this, people ask you, “Why do you do it?” I tried to be honest and said, “I’m going to walk to the North Pole.” But they thought it was a joke. So, eventually I said it was a bachelor party, which everybody believed.

It’s lots of physical training, but the most important thing is to know what’s happening in the mind. Because physical-wise, quite a few people can do it. But, being a polar explorer, the greatest challenge today is the same as 100 years ago: to get up in the morning. You have to be willing to ski for eight, 10, maybe even 15 hours, as the temperatures go down to -64 Fahrenheit, dragging 250 pounds. It’s tough going. What’s happening with your legs is important—but most important is what’s happening between your ears.

And on mornings when you wake up, and it is unbelievably cold and you don’t want to move, how do you make yourself get up on days like that?

All you want to do is to stay in the sleeping bag for another five minutes—or five hours. In the sleeping bag, you freeze a little. But when you get out of the sleeping bag, you freeze like hell. But as soon as you’re out of the sleeping bag, and you take down the tent, everything seems so much better. The weather’s usually better outside the tent than you imagine it is when you’re inside the tent.

Are there lessons you’ve learned on these treks that you then incorporate into your daily life in Norway?

One thing you learn when you walk really far is that so many things that you’re concerned about on a daily basis really don’t matter. Also you learn that most things have a solution and that solution is really usually quite close by.

You think better when you walk. Obviously you won’t become Steve Jobs just by walking. But it’s a good start. What’s interesting is that at Stanford University, in 2015, they started research on it and they confirmed what we know: you become much more creative by walking. Charles Darwin had his own walking path—every time he’d get stopped up in his head, he took a little walk.

You talk about walking backwards as a way to be mindful. I’m curious if you have other things in your life like that? Other techniques that bring you back to the present?

In the silence, it’s about shutting out the world, not thinking about anything else. Maybe to not think at all. Because when you think, you think about the past or the future. I can find the silence when I cook breakfast for my kids, when I make their porridge. I can find it when I walk to the Metro station in the morning or to my office. I can find when I walk up the stairs. I’ll find it when I’m having sex. I can find it when I’m jogging. I can find it when I’m climbing. I find it eventually when I’m cooking. And I definitely find it when I do the dishes because nobody will disturb me. And I can find it again when I go to bed.

So the silence is there all the time. It’s waiting for you. I think it may be wise to use techniques to find it, like mindfulness and meditation. But the silence I have been after and the silence I experience when I’m walking, that is silence that does not require any techniques.

If you could give a 25-year-old Erling advice, what would you tell him?

Most people underestimate the possibilities you have in life. And that’s a bit sad. So much of society is based upon narrowing people’s minds as much as possible. But don’t underestimate yourself. Also, like I said: Get up in the morning.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

April 24th 2024

In Knife, his memoir of surviving attack, Salman Rushdie confronts a world where liberal principles like free speech are old-fashioned

Published: April 19, 2024 8.38am BST

Author

- Paul Giles Professor of English, Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, ACU, Australian Catholic University

Disclosure statement

Paul Giles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Australian Catholic University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

We believe in the free flow of information

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

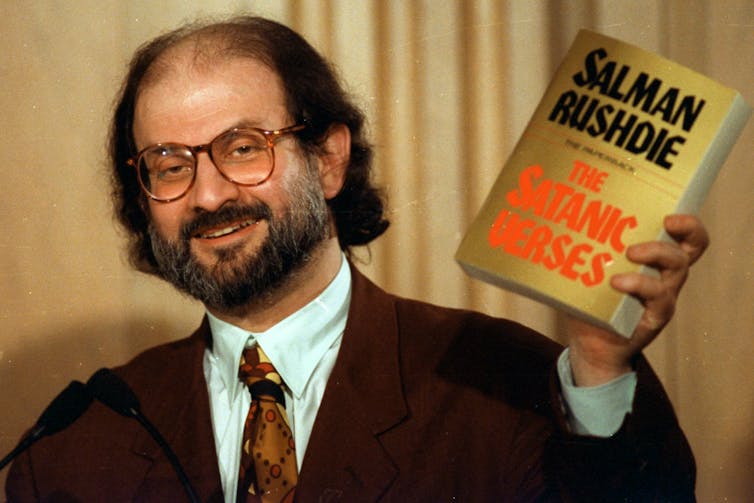

Knife is Salman Rushdie’s account of how he narrowly survived an attempt on his life in August 2022, in which he lost his right eye and partial use of his left hand. The attack ironically came when Rushdie was delivering a lecture on “the creation in America of safe spaces for writers from elsewhere”, at Chautauqua, in upstate New York.

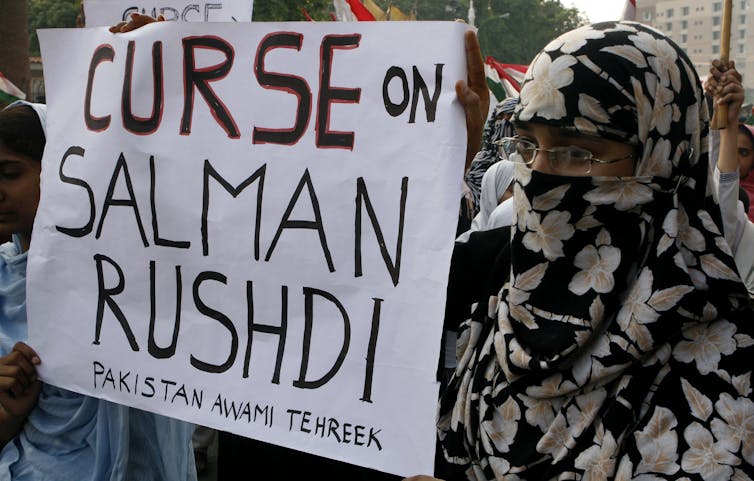

A man named Hadi Matar has been charged with second-degree attempted murder. He is an American-born resident of New Jersey in his early twenties, whose parents emigrated from Lebanon. Prosecutors allege the assault was a belated response to the fatwa, a legal ruling under Sharia law, issued in 1989 by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

The Iranian leader called for Rushdie’s assassination after the publication of the author’s novel The Satanic Verses, which allegedly contained a blasphemous representation of the prophet Muhammad. Matar has pleaded not guilty to the charge, and his trial is still pending.

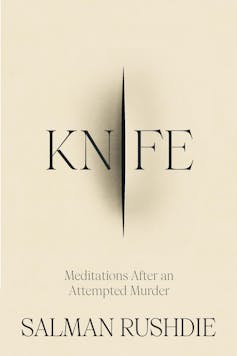

Review: Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder – Salman Rushdie (Jonathan Cape)

Knife is very good at recalling Rushdie’s grim memories of the attack. (His assailant appears in this book merely under the sobriquet of “the A”.) It also articulates with typically dry, self-deprecating humour the dismal prognoses of his various doctors. These are balanced against his own incorrigible sense of “optimism” and ardent will to live, along with the staunch love and support of his new wife, the writer and artist Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

This is a book where you can feel the author wincing with pain. “Let me offer this piece of advice to you, gentle reader,” he says: “if you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut … avoid it. It really, really hurts.”

But at the same time, it is a story of courage and resilience, with Rushdie cheered by the unequivocal support he receives from political leaders in the United States and France, as well as writers around the world. He cites as a parallel to his own experience the Charlie Hebdo attacks in France, in which 12 people were murdered in the Paris offices of a satirical magazine that had supposedly defamed the Islamic Prophet.

While the author’s personal recollections of this traumatic event are powerful, the declared aim of Knife is to “try to understand” the wider context of this event. Here, for a number of reasons, Rushdie is not on such secure ground.

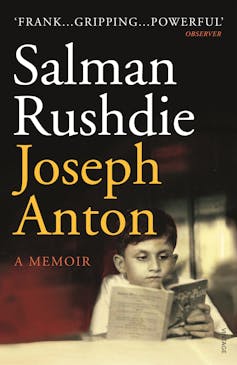

One of his great strengths as a novelist is the way he presents “worlds in collision […] quarrelling realities fighting for the same segment of space-time”. This phrase comes from his 2012 memoir Joseph Anton, the pseudonym he used during his years of protection by British security services in the immediate aftermath of the fatwa.

Read more: How Salman Rushdie has been a scapegoat for complex historical differences

Rushdie, who studied history at Cambridge University, described himself in Joseph Anton as “a historian by training”. He said “the point of his fiction” is to show how lives are “shaped by great forces”, while still retaining “the ability to change the direction of those forces” through positive choices.

The second part of Knife is focused around Rushdie’s unwavering commitment to the principles of free speech in his work for PEN and other literary organisations. Indeed, a speech he gave at PEN America in 2022 is reprinted in the book verbatim.

“Art challenges orthodoxy,” declares Rushdie. He associates himself with a legacy of Enlightenment thinkers going back to Thomas Paine, whose work influenced both the American and French Revolutions. For these intellectuals, principles of secular reason and personal liberty should always supersede blind conformity to social or religious authority.

Old-fashioned liberal principles

In Knife, though, Rushdie the protagonist confronts a world where such liberal principles now appear old-fashioned. He claims “the groupthink of radical Islam” has been shaped by “the groupthink-manufacturing giants, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter”.

But for many non-religious younger people, any notion of free choice also appears illusory, the anachronistic residue of an earlier age. Millennials and Generation Z are concerned primarily with issues of environmental catastrophe and social justice, and they tend to regard liberal individualism as both ineffective and self-indulgent.

As a perceptive social historian, Rushdie notes how “new definitions of the social good” have arisen, in which “protecting the rights and sensibilities of groups perceived as vulnerable […] take precedence over freedom of speech.”

Knife itself is understandably reductive, even dismissive, in its treatment of the assailant. The author contemplates the prospect of a meeting with him, but decides that is “impossible” and so tries to “imagine my way into his head” by inventing an “imagined conversation”. But this is not entirely convincing.

Rushdie’s point about how the Quran itself is immersed in the worlds of “interpretation” and “translation” might work well in a seminar on world literature, but it is hardly the kind of argument likely to persuade a jihadist who, on his own admission, has read only two pages of The Satanic Verses.

Rushdie’s stylistic tendency to dehumanise his characters is characteristically humorous and perhaps therapeutic. He renames his ear, nose and throat doctor “Dr. ENT, as if he were an ancient tree-creature from The Lord of the Rings”. But it also carries the risk of diminishing his characters to puppets being manipulated by the author.

This is the kind of power relation interrogated self-consciously in Fury (2001) and other fictional works that explore the limitations of authority. Rushdie is a great novelist because of his openness to questions about the scope of authority and authorship, but he is a less effective polemicist. The structural ambiguities and inconsistencies that enhance the multidimensional reach of his fiction tend to be lost when he takes on the mantle of a political controversialist.

Knife hovers generically in between these two positions. One of the book’s most interesting aspects is its probing of the weird and supernatural. Two nights before his attack, the author dreams of being assaulted by a man with a spear in a Roman amphitheatre. Citing Walt Whitman on the uses of self-contradiction, he records: “It felt like a premonition (even though premonitions are things in which I don’t believe).”

Similarly, he describes his survival, with the knife landing only a millimetre from his brain, as “the irruption of the miraculous into the life of someone who didn’t believe that the miraculous existed”. Later, he observes: “No, I don’t believe in miracles, but, yes, my books do.”

This speaks to a paradoxical disjunction between the relative narrowness of authorial vision and the much wider scope of imagined worlds that Rushdie’s best fiction evokes.

Suffused in the culture of Islam

The Satanic Verses itself is suffused in the culture of Islam as much as James Joyce’s Ulysses is suffused in the culture of Catholicism. In both cases, the question of specific religious “belief” becomes a secondary consideration.

In their hypothetical conversation, the author of Knife tries to convince his assailant of the value of such ambivalence. He protests how his notorious novel revolves around “an East London Indian family running a café-restaurant, portrayed with real love”.

But of course such subtleties are hopelessly wasted on an activist who has no interest in literary nuances and who desires only to execute the instructions of a religious leader. Given the prevalence of what Rushdie calls the contemporary “offence industry,” it is sobering to think that Ulysses, if published today, could be more liable to censorship for blasphemy rather than, as in 1922, obscenity.

In many ways, then, Knife is a book about cultural cross-purposes. Though Rushdie is understandably vituperative on a personal level, his work’s conceptual undercurrents turn on the fate of the liberal imagination in an increasingly post-liberal world.

There are moving tributes here to the writers Martin Amis and Milan Kundera, friends who died recently. There are also melancholy acknowledgements of illnesses suffered by Paul Auster and by Hanif Kureishi, whom Rushdie regards as his “younger-brother-in literature”.

This generation of writers saw the multifaceted nature of fiction, with its inclinations towards magical realism, as a way to resist what Joseph Anton calls the potentially “flattening effect” of political slogans. Amis believed one of the reasons for the general decline of interest in reading literature was a new preference for the security of ready-made solutions rather than experiential challenges.

Read more: Milan Kundera’s ‘remarkable’ work explored oppression, inhumanity – and the absurdity of being human

Attachment to past traditions

But in the era of Facebook and Twitter, brevity and simplicity have become more compelling than complexity. This categorical shift has been shaped not only by the explosion of information technology, but also the de-centring of Europe and North America as undisputed leaders of intellectual and political culture.

Rushdie discusses in Knife how, besides the Hindu legends of his youth, he has also been “more influenced by the Christian world than I realized”. He cites the music of Handel and the art of Michelangelo as particular influences. Yet this again highlights Rushdie’s attachments to traditions firmly rooted in the past.

Whereas the dark comedy of Michel Houellebecq depicts an environment in which advances in biogenetics, information technology and political authoritarianism have rendered individual choice of little or no consequence, Rushdie gallantly flies the flag for privacy and personal freedom.

But he is also describing a world where such forms of liberty seem to be passing away. In that sense, Knife feels like an elegy for the passing of an historical era.

The memoir recalls how Rushdie’s “first thought” when his assailant approached was the likely imminence of death. He cites the reported last words of Henry James: “So it has come at last, the distinguished thing.”

James, like Rushdie, was a writer who lived through profound historical changes, from the Victorian manners represented in his early stories to new worlds of mass immigration and skyscrapers portrayed in The American Scene (1907).

Part of James’s greatness lay in the way he was able to accommodate these radical shifts within his writing. Rushdie is equally brave and brilliant as a novelist, and he may well ultimately succeed in capturing such seismic shifts, but Knife is not a work in which his artistic antennae appear to their best advantage.

Though Rushdie specifically says he “doesn’t like to think of writing as therapy”, he admits sessions with his own therapist “helped me more than I am able to put into words”. The writing of this book clearly operates in part as a form of catharsis, with Rushdie admitting his fear that “until I dealt with the attack I wouldn’t be able to write anything else”.

Read more: Reading French literature in a time of terror

‘A curiously one-eyed book’

There are many valuable things in Knife. Particularly striking are the immediacy with which he recalls the shocking assault, the black humour with which he relates medical procedures and the sense of “exhilaration” at finally returning home with his wife to Manhattan.

Yet there are also many loose ends, and the book’s conclusion, that the assailant has in the end become “simply irrelevant” to him, is implausible. Rushdie presents his survival as an “act of will” and is adamant he does not wish henceforth to retreat into the security cocoon that protected him during the 1990s. He insists he does not want to write “frightened” or “revenge” books. In truth, however, Knife contains elements of both these traits.

As a congenital optimist, Rushdie says he takes “inspiration” from the Nawab of Pataudi (given name Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi), an Indian cricketer whose illustrious career began after he had been “involved in a car accident and had lost the sight of one eye”.

But Rushdie does not mention the similar fate suffered by Colin Milburn, an England international cricketer who lost an eye in a car accident in 1969 and who was never able to recover his sporting career. This was despite several brave comeback attempts by Milburn that likewise cited Pataudi as an example.

Rushdie is a remarkable novelist, whose epic work Midnight’s Children (1981) has twice (in 1993 and 2008) been voted the best-ever winner of the Booker Prize. Knife, by contrast, is a curiously one-eyed book, in a metaphorical, as well as a literal sense.

The author declares his intention to use his own artistic language as “a knife” to “cut open the world and reveal its meaning”. But the challenge for the rest of his writing career will surely involve deploying his extraordinary talents to assimilate these experiences in a more expansive fashion.

This should enable Rushdie to address, like Henry James in his ambitious late phase, the intricate entanglements of a changing world.

- Free speech

- Liberalism

- Memoir

- Book reviews

- Charlie Hebdo

- fatwa

- Salman Rushdie

- Qur’an

- Satanic Verses

- Midnight’s Children

- Trauma memoirs

- PEN America

March 22nd 2024

March 20th 2024

Understanding The White Gaze And How It Impacts Your Workplace

Senior Contributor

I help create strategies for more diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Dec 28, 2021,07:39pm EST

The white gaze is a term popularized by critically acclaimed writer Toni Morrison. When describing how it operates, Morrison said that it’s this idea that “[Black] lives have no meaning and no depth without the white gaze.” In the simplest terms, the white gaze can be conceptualized as the assumed white reader. When writers craft stories, the assumed white (and often cisgender, heterosexual, male) audience that they are writing for and to is the white gaze in action. The white gaze can be expanded to mean the ways in which whiteness dominates how we think and operate within society. Being encouraged to adhere to white-centered norms and standards is one of the ways that the white gaze operates. To create a world, and more specifically a workplace, that is built on equity, understanding the ways that the white gaze shows up is imperative.

The white gaze is present in innumerable ways in the workplace, with some manifestations being more prevalent than others. Non-white employees sometimes report experiences of the policing of their bodies within the workplace. One of the ways that this is expressed is via standards of professionalism and perfectionism, Aysa Gray elucidates. A quick perusal of corporate policies may reveal discriminatory practices that impact racialized employees. Hair discrimination, for example, affects Black employees because of the notion that Black hair in its most natural state is unprofessional. While some places within the United States are adopting protections for hair discrimination, those who experience this type of discrimination aren’t shielded in every state. Those who work outside of the U.S. may not be protected at all. Corporations often have vague appearance policies, which assumes that there is a one-size-fits-all standard of professionalism. If your workplace, for example, requires hats to be worn as part of a uniform, do the hats fit all hair textures? For employees with thicker and more coarse hair, having a uniform that takes their hair texture into consideration contributes to an inclusive work culture. These subtle nuances are often overlooked since corporate policies and practices are crafted with a white worker in mind.

In a groundbreaking study conducted by Verónica Caridad Rabelo, Kathrina J. Robotham, and Courtney L. McCluney, the researchers examined over 1,000 tweets under the hashtag #BlackWomenAtWork to assess trends about how the white gaze is experienced by Black women in the workplace. One theme that emerged in their research was the experience of “whiteness as venerated,” which results in whiteness being seen as superior. This can equate to Black women employees being viewed as “incompetent,” which results in lower performance evaluations. A study from the NewsGuild of New York found that employees of color were far more likely to receive low performance reviews compared to their white counterparts. One of the most insidious ways that non-white employees experience the white gaze is via performance evaluations.

In the aforementioned Rabelo, Robotham & McCluney study, another theme that emerged from the research was the expectation of Black women’s “time, attention, praise, and ideas.” There is a whole other discussion to be had about the co-opting of Black women’s ideas. There is a common practice of racialized employees being used for their education and labor. Since the murder of George Floyd, the desire to learn more about race and racism has amplified. Employees from racially marginalized backgrounds often bear the burden of educating and enlightening white colleagues. There are not enough conversations being had about the impacts of resharing stories of past racial trauma, and how it can re-traumatize individuals who already experience a great deal of racial harm. There is an expectation, Rabelo, Robotham & McCluney note, that many Black women feel where they must participate in conversations about race, even when they have no interest. An example of this could be having to explain what “white privilege” is to a coworker. For many racialized employees, there is an expectation of “performance” in one way or another.

The white gaze also materializes as stereotypes that are applied to different racial groups in the workplace. The bamboo ceiling impacts Asian employees because of assumptions that Asian workers do not possess the skills and abilities that are typically associated with leaders. The problem lies in the fact that Asians, along with other racialized communities, are being measured based on a white and Eurocentric scale. Brianna Holt wrote a compelling piece about how Black women are not allowed to be introverted at work. Women from racialized groups experience tone policing and get ascribed to negative stereotypes based on this white measuring stick. The white gaze continues to cripple non-white workers and until leadership a) understands the white gaze and b) recognizes how to mitigate it, racialized employees will continue to suffer.

Companies committed to interrupting the white gaze must focus on a few things. No progress can be made without education, understanding, and awareness of how the white gaze operates. Bring in consultants, speakers, and researchers to educate employees about the white gaze. Have a human resource consultant that specializes in diversity, equity, and inclusion review workplace policies and practices. You may be surprised to learn that policies that seem benign on the surface are actually exclusionary to different populations of workers. Be intentional about involving more racialized employees in decision-making processes. Also recognize that the white gaze isn’t exclusive to just white people; racialized groups growing up in a white-dominant society often internalize negative stereotypes about their own group (which can lead to colorism, anti-blackness, and white adjacency). Despite this, involving people from different racialized backgrounds into the decision-making process may somewhat mitigate the white gaze, but education is the foundation of all other interventions. Lastly, workplaces striving to disrupt the white gaze should encourage education about different racialized groups. This is not only done through books, but via movies, shows, podcasts, and YouTube videos. Instead of having anti-racist book clubs, which some argue may not be effective, saturate employees in alternative forms of education to better their understanding of groups outside of their own.

Janice Gassam Asare

March 18th 2024

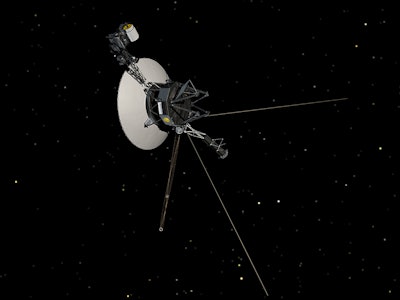

The Satellite Hack Everyone Is Finally Talking About

As Putin began his invasion of Ukraine, a network used throughout Europe—and by the Ukrainian military—faced an unprecedented cyberattack that doubled as an industrywide wake-up call.

By Katrina Manson

Illustrations by Jordan Speer

1 March 2023 at 00:01 GMT

Andreas Wickberg loves snowmobiling to the house he built in the icy reaches of Lapland, north of the Arctic Circle. Each month come spring, he and his wife relocate for a week or so to a “very, very isolated” spot about 335 miles northwest of their usual home near Umea, a Swedish university town. Up in Lapland, it’s just them and three other houses. Wickberg develops payment-processing software for a Swedish e-commerce company. What makes this possible is satellite internet: For 500 krona ($45) a month, he and his wife can make work calls by day and stream movies by night.

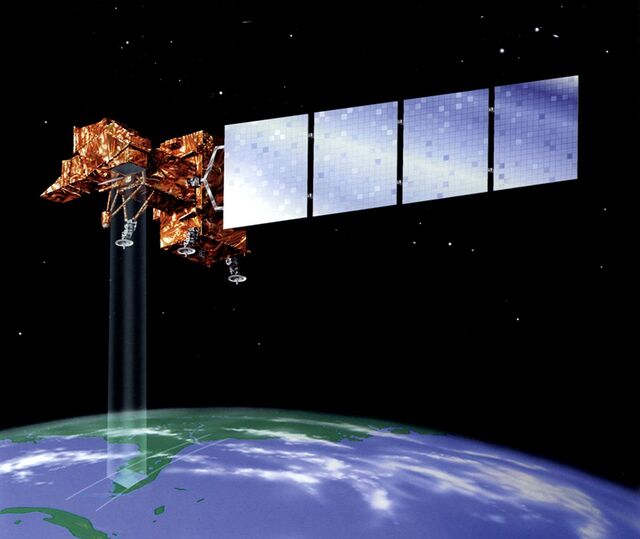

Just over a year ago, though, they and their neighbors found themselves cut off from the outside world. At 7 a.m. on Feb. 24, 2022, Wickberg turned on his computer and took in the news that Russian President Vladimir Putin had begun an invasion of Ukraine with airstrikes on Kyiv and many other cities. Wickberg read everything he could, aghast. Not long after, a neighbor came around asking to borrow the family’s Wi-Fi password because their internet was on the fritz. Wickberg obliged, but 10 minutes later, his connection dropped, too. When he checked his modem, all four lights were off, meaning the device was no longer communicating with KA-SAT, Viasat Inc.’s 13,560-pound satellite floating 22,236 miles above.

Courtesy Airbus

The way each of the connections in his community switched off one by one left him convinced that this wasn’t just a glitch. He concluded Russia had hacked his modem. “It’s a scary feeling,” Wickberg says. “I actually thought that these systems were much more secure, that it was sort of far-fetched that this could even happen.”https://www.bloomberg.com/api/embed/iframe?id=397368689&location=interactive&idType=AVMM

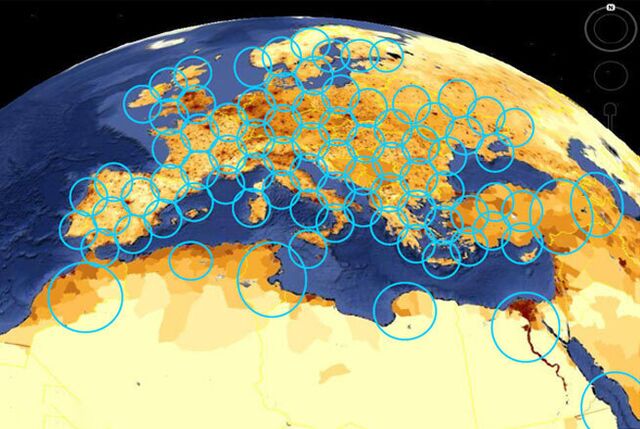

Viasat staffers in the US, where the company is based, were caught by surprise, too. Across Europe and North Africa, tens of thousands of internet connections in at least 13 countries were going dead. Some of the biggest service disruptions affected providers Bigblu Broadband Plc in the UK and NordNet AB in France, as well as utility systems that monitor thousands of wind turbines in Germany. The most critical affected Ukraine: Several thousand satellite systems that President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s government depended on were all down, making it much tougher for the military and intelligence services to coordinate troop and drone movements in the hours after the invasion.

“I just bought some cheap antennas, pointed them at some satellites and found I could clean up the data from the signals, because nothing is encrypted”

Alerts from customers, engineers and automated systems soon began to flood in via phone, Slack and email, according to a senior Viasat executive who was part of the response team and spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. Attackers were overwhelming the customers’ modems with a barrage of malicious traffic and other kinds of attacks. It took Viasat hours solely to stabilize most of its network, and the official says it then spent many weeks fending off subsequent attacks of “increasing intensity.”

It would take 35 days for Viasat to even begin to say publicly what it thought had happened, and 75 days for any country to point the finger officially at Russia. In the meantime, Ukrainian officials trying to reach remote locations were forced to rely where they could on landlines, cellphones, even dispatching runners to reach the front lines. “Industry was caught flat-footed,” says Gregory Falco, a space cybersecurity expert who has advised the US government. “Ukrainians paid the price.”

While Zelenskiy and his deputies have mostly declined to discuss the hack’s impact on their operations, Viktor Zhora, a senior Ukrainian cybersecurity official, told reporters last year that it resulted in “a really huge loss in communications.” The Russian Embassy in Washington denies any responsibility for the attack, dismissing blame as “detached from reality.”

Space ISAC

The attack was, however, a wake-up call. “The war is really just revealing the capabilities,” says Erin Miller, who runs the Space Information Sharing and Analysis Center, a trade group that gathers data on orbital threats. Cyberattacks affecting the industry, she says, have become a daily occurrence. The Viasat hack was widely considered a harbinger of attacks to come.

Just about every day, more people around the world rely on satellite internet connections than did the day before. Yet for decades, industry specialists say, the commercial satellite industry has underinvested in security measures and essentially ignored what might happen if its systems were hacked on a grand scale. There are 5,000 active satellites circling the planet, and high-end estimates predict the number will top 100,000 by the end of the decade. While smaller, cheaper satellites are being launched into orbit by the thousands, the machines and the networks that run them remain woefully insecure. Customers who rely on them need a backup plan.

For decades after the dawn of the Space Age, nobody worried much about making satellites tamper-proof—it was tough enough just to put them in orbit. By the 1980s, though, there were more sat systems to play with, and spies and amateurs alike started figuring out how to do it. In 1986, John MacDougall, an American engineer who dubbed himself Captain Midnight, jammed HBO’s signal to protest fee hikes. Today, China, Russia, the US and dozens of other nations have demonstrated that they can hack stuff in space, according to James Pavur, a cybersecurity researcher who recently went to work for the Pentagon as a digital service expert. His research has shown just how easy it is to hack an orbiting satellite, its data transmissions or the ground networks that support them.

Courtesy YouTube

Almost all of daily life entails some use of satellites. GPS coordinates and space-based relays are an essential component not only of global communications, military operations and weather forecasting, but also of farms, power grids, transportation networks, ATMs and some digital clocks. All 16 infrastructure sectors the US has designated as critical “depend to a great extent, pretty much all of them, on space systems,” says Sam Visner, a former chief of the National Security Agency’s Signals Intelligence programs who’s now vice chair of the Space ISAC. Visner has argued for years that satellite systems aren’t secure enough, including the ground stations. Pavur says this gear has been hacked at least two dozen times in the past decade or so. As part of his 2019 doctoral thesis at the University of Oxford, he intercepted sensitive communications beamed down to ships and Fortune 500 companies, including crew manifests, passport details and credit card numbers and payments, all with $400 worth of home equipment. “It turns out to be easy,” he says. “I just bought some cheap antennas, pointed them at some satellites and found I could clean up the data from the signals, because nothing is encrypted.”

In the year before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the US intelligence community warned publicly and privately that Russia was testing its ability to hack and destroy satellite systems. Even so, it remained easy for companies to underestimate the risks—partly because there were so many new intermediaries between them and end users, and partly because space still seemed untouchable. Denial was the norm, allowing businesses to save on infrastructure spending while leaving no single company more responsible than another for a potential catastrophe.

A month before the modems went dead, the NSA issued a warning about multiple vulnerabilities in commercial satellite equipment and recommended a series of security-conscious practices, including encryption, password changes, software updates and steps to keep network management systems isolated from one another. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency also gave classified briefings to industry leaders. President Joe Biden was preparing for the possibility that Russia would invade Ukraine, and he wanted to assess what kinds of cyberattacks Putin might retaliate with if the US imposed economic sanctions, according to a White House official familiar with his thinking, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss national security matters. The official, who says companies need to radically improve the security of satellite ground systems, also says the federal government regularly asks companies privately to patch particular vulnerabilities, and some just don’t.

NASA

The senior Viasat executive says the NSA’s public warning was too vague to serve as a real heads-up. He says the company discussed it with the agency and concluded it wasn’t specifically relevant to Viasat’s operations, which include beaming Wi-Fi connectivity to sensitive government aircraft. But the NSA cited a 2018 paper by Ruben Santamarta, an independent cybersecurity researcher, that might’ve given the company pause. He’d concluded that flaws in a network’s configuration—the settings that keep it running—could leave military modems hackable.

Santamarta says the critical vulnerability of satellite ground systems was plain as day back in 2014, when he wrote a different paper outlining how an invading military could hack and disable mobile satellite terminals and head off a counterattack. When he presented that one, the industry downplayed the threat. Until last year he’d never seen the attack he’d described in real life, but pages 10 and 11 of the 2014 paper, he says, are “literally what happened in Ukraine.”

“If a threat actor has access to the management system, it’s almost game over”

NASA

In the weeks after the attack, Wickberg, who read a blog post Santamarta had written about it, sent the researcher one of the affected modems. Santamarta began pulling the hacked device apart with a screwdriver and a hot air gun, using a special reader to examine its rewritable flash memory. In a normal modem, the code that runs the device appears as a bunch of different numbers and word strings. Instead, Santamarta saw a meaningless pattern—junk data that had wiped the modem clean. “It was basically garbage,” he says. After further review, he concluded the modem could be overwritten without any kind of authentication. In other words, Viasat left a door open.

The same day Santamarta was dissecting the modem, Viasat issued an opaque statement that essentially blamed one of its corporate partners. Viasat had flown afflicted modems to California for its own inspections and reverse-engineered the hack, then traced the wiper malware to a management network server, where it discovered what appeared to be a malware toolkit. A month later, with its broadband service still in disarray, Viasat suggested the hack had taken advantage of an embarrassingly basic hole in a part of the network run by Skylogic SpA. Skylogic was meant to secure the system with virtual private network software. “Subsequent investigation and forensic analysis identified a ground-based network intrusion by an attacker exploiting a misconfiguration in a VPN appliance,” Viasat said in its statement. Mark Dankberg, then the company’s executive chairman, said the attack “was preventable, but we didn’t have that capability.”

Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters

Skylogic’s parent company, the French telecom Eutelsat Communications SA, acknowledges that a VPN in Turin, Italy, where Skylogic is based, was the entry point for the hack, but denies responsibility. It says that the key flaws were in Viasat’s modem equipment, the target of the advanced attack, and that flaws in the user part of the ecosystem were a “well-known fact.” Santamarta says hacking one part of a complex network shouldn’t give you access to all of it. “If a threat actor has access to the management system, it’s almost game over,” he says.

In the wake of the hack, neither company mentioned seeking out the perpetrator or uttered the name Russia. For months, Viasat declined further public comment on the matter, irking US officials, peers and researchers. It simply replaced more than 45,000 affected modems and kept its head down. Privately, Viasat executives joined a classified briefing about the hack that the US intelligence community gave to a range of worried commercial space companies in late March, according to several attendees. Some guests received security clearances for the day. While one attendee says the briefing lacked key details required to put reforms into action, another says it succeeded at one thing: forcing the issue.

Under a Hack

An attacker has lots of ways to get into a satellite internet network. Here’s what happened to Viasat’s KA-SAT, and what didn’t.https://www.bloomberg.com/toaster/v2/charts/6ca25b45adaf4cb6a282589a9e1f8804?hideLogo=true&hideTitles=true&web=true&

By then, US officials had begun telling reporters that Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU, was responsible for the attack. Researchers determined that a piece of malware called ukrop, which had been anonymously uploaded to a public repository in mid-March, was the same wiper used against Viasat. (Ukrop is a Russian slur for Ukrainians but could also be short for “Ukraine operation.”) In the malware’s code, they found similarities to a 2018 virus that the US had attributed to a Russian hacking group with alleged GRU ties.

One of the most significant insights US intelligence gleaned was that the Russians were prepared to take significant diplomatic and strategic risks. They knew spillover from the satellite attack would affect countries outside Ukraine but decided to proceed anyway.